Standing at the edge of the Atacama Desert, you can see the Pacific Ocean stretching endlessly to the west. Yet beneath your feet lies one of the driest places on Earth, where some spots have waited centuries for a single rainstorm.

How can a place be parched when an ocean sits literally next door, full of water?

1. First, a quick truth-check: “driest on Earth” depends on how you measure it

When people call the Atacama the driest place on Earth, they’re usually talking about non-polar deserts. That’s an important distinction.

If you count polar regions, Antarctica actually takes the crown for absolute dryness. The McMurdo Dry Valleys in Antarctica receive almost no precipitation and are often considered the driest spots on the planet overall.

So why does the Atacama get so much attention? Because it’s the driest warm desert, and it’s far more accessible than Antarctica.

Researchers can visit year-round without needing icebreakers or extreme cold-weather gear.

The Atacama also has a unique combination of factors that make it hyperarid. Polar deserts are dry because the air is too cold to hold moisture.

The Atacama, however, sits at lower latitudes where you’d normally expect more rain.

Understanding how “driest” is measured helps us appreciate what makes this desert so unusual. Whether you rank it first or second globally, the Atacama remains one of Earth’s most extreme environments.

Its dryness isn’t just a number on a chart but a landscape shaped by forces working together in rare harmony.

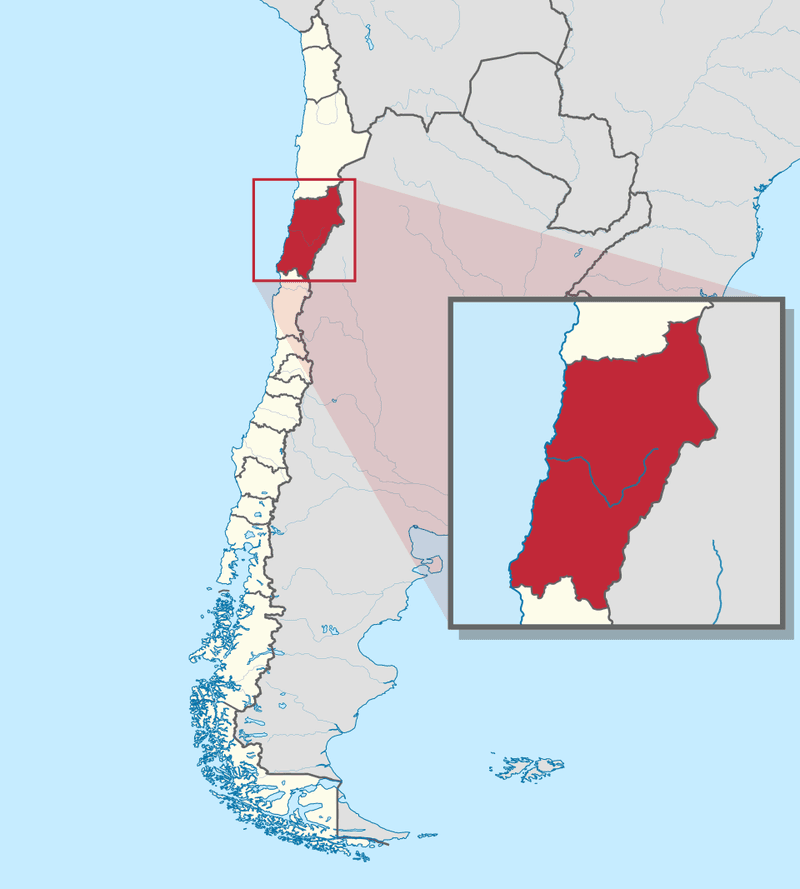

2. It sits in a geographic squeeze: Pacific on one side, Andes on the other

On the western edge, the Pacific Ocean rolls in with endless waves. Just inland, the Andes mountain range towers skyward, creating one of the steepest elevation changes anywhere on Earth.

This geographic sandwich creates the Atacama’s basic layout. The desert runs roughly north to south along Chile’s coast, squeezed into a corridor that’s sometimes only 50 to 100 miles wide.

That positioning isn’t random; it’s everything.

Mountains and oceans are both powerful climate shapers on their own. When they team up this closely, they create extreme conditions.

The Andes block weather systems moving from the east, while the Pacific’s cold currents stabilize the air from the west.

Being trapped between these two forces means the Atacama can’t catch a break. Moisture that might arrive from either direction gets intercepted or shut down.

The result is a slender ribbon of land where rain almost never falls, despite being wedged between a massive ocean and moisture-bearing mountains. Geography dealt this desert a tough hand.

3. Rain shadow, level: brutal

Rain shadows happen when mountains block moisture-carrying winds, forcing air upward. As air rises, it cools and drops its moisture on the windward side.

By the time it crosses the peaks and descends on the other side, it’s wrung dry.

The Andes create one of the most intense rain shadows on the planet. Winds carrying moisture from the Amazon basin and the continental interior hit this massive wall of rock.

The mountains force that air up, and precipitation falls on the eastern slopes, never reaching the Atacama.

What makes this rain shadow especially brutal is the sheer height of the Andes. Some peaks tower above 20,000 feet, creating an impenetrable barrier.

Air masses lose every drop of moisture before they ever see the desert.

Even winds trying to approach from the east get stopped cold. The Atacama sits in the rain shadow’s driest zone, where descending air warms and dries further.

It’s a double whammy: blocked moisture plus warming, drying winds. That combination turns the rain shadow into a dryness engine running at full throttle.

4. The ocean is right there… but it doesn’t “deliver” rain

Oceans are usually rain factories. Warm water evaporates, rises, forms clouds, and eventually falls as precipitation.

That’s how tropical coasts get drenched year-round. So why doesn’t the Pacific deliver rain to the Atacama, which sits right on its shore?

The answer lies in water temperature. The Pacific along Chile’s coast isn’t warm; it’s surprisingly cold.

Cold water doesn’t evaporate as readily, so less moisture enters the air in the first place.

Even when some evaporation occurs, the cooled air near the surface stays stable. Stable air doesn’t rise vigorously, so clouds form but don’t develop into towering storm systems.

You end up with low-lying fog and overcast skies instead of rain.

Walking along the Atacama coast can feel surreal. You hear waves crashing, smell salt in the air, and see gray clouds overhead.

Yet no rain falls. The ocean is close enough to touch, but it withholds the one thing the desert needs most.

That strange disconnect is what makes the Atacama’s dryness so puzzling at first glance.

5. The Humboldt Current helps shut down storms before they start

Ocean currents shape climate in powerful ways, and the Humboldt Current is a major player along South America’s west coast. Also called the Peru Current, it flows northward from Antarctica, carrying cold water up along Chile and Peru.

That chilly water has a huge impact on the Atacama.

Cold ocean surfaces cool the air sitting directly above them. Cool air is denser and more stable than warm air, so it resists rising.

Without rising air, you can’t get the vertical development needed to build rain clouds and thunderstorms.

The Humboldt Current essentially caps the atmosphere near the coast. Moisture might be present, but it stays trapped in a shallow layer close to the ground.

Clouds form, but they’re thin and low, never growing tall enough to produce significant rainfall.

Think of the current as a storm-suppression system running 24/7. While other coasts enjoy regular showers from ocean-fed weather systems, the Atacama gets shut down before storms can even begin.

The Humboldt Current is one of the key reasons this desert stays so relentlessly dry despite its oceanfront location.

6. High pressure systems “park” over the region

Atmospheric pressure patterns control where storms form and where skies stay clear. High-pressure systems are zones where air sinks downward, warms up, and dries out.

They’re associated with stable, calm weather and few clouds. The Atacama sits under a persistent high-pressure zone called the South Pacific High.

This high-pressure system doesn’t just pass through; it parks over the region for long stretches. Sinking air inside the system compresses and warms, which lowers relative humidity.

Any moisture that might have been present evaporates rather than condensing into rain.

Because the high-pressure zone is so stable, normal weather cycles don’t break through. Storms that might bring rain get steered away or weakened before they arrive.

The desert stays locked in a pattern of clear skies and dry air.

High-pressure systems are common worldwide, but the South Pacific High is unusually strong and persistent. Combined with the other factors working against rain in the Atacama, this atmospheric feature seals the deal.

The region gets stuck in a weather rut where rain simply doesn’t fit into the forecast.

7. Some parts get tiny annual rainfall totals

Numbers can be abstract until you see them in context. Parts of the Atacama average about 0.03 inches of rain per year.

To put that in perspective, most major cities get 30 to 50 inches annually. Some tropical areas exceed 100 inches.

The Atacama gets less in a year than most places get in a single hour during a storm.

Point-zero-three inches is roughly the thickness of a credit card. Imagine waiting an entire year for that much water to fall from the sky.

In the hyperarid core of the desert, even that tiny amount might not arrive every year.

These measurements come from weather stations that have operated for decades. They confirm what the landscape already suggests: this is one of the most rain-starved places imaginable.

Some years bring zero measurable precipitation.

Such extreme dryness creates a landscape unlike anywhere else. Rivers don’t flow.

Lakes don’t form. Vegetation is nearly absent in the driest zones.

The ground is often described as resembling Mars more than Earth. Those tiny rainfall totals aren’t just statistics; they define an entire ecosystem and shape how humans interact with this unforgiving land.

8. About that “centuries without rain” claim: it’s real, but it’s also specific

You’ve probably heard the dramatic claim: parts of the Atacama went 400 years without rain. It sounds almost impossible, yet it’s rooted in historical records.

The commonly cited period runs from roughly 1570 to 1971, when certain weather stations recorded no significant rainfall.

That claim needs unpacking. “Significant” is key here. Trace amounts or tiny sprinkles might have occurred but didn’t meet the threshold for official recording.

Also, not the entire Atacama went rain-free; specific hyperarid pockets experienced this extreme drought.

Weather station data from the colonial era and early modern period can be sparse. Researchers piece together records from mission logs, mining reports, and later scientific observations.

The 400-year figure represents the best estimate for certain locales, not a blanket statement about the whole region.

Even with those caveats, the claim is remarkable. Four centuries is longer than the United States has existed.

It’s a timespan that saw empires rise and fall, yet some parts of the Atacama stayed bone-dry the whole time. Understanding the nuance doesn’t diminish the wonder; it just keeps us grounded in what the evidence actually shows.

9. Fog replaces rain: meet the camanchaca

Along the Atacama coast, mornings often bring a thick blanket of fog rolling in from the ocean. Locals call it camanchaca, and it’s as close to rain as many areas ever get.

The fog forms when cold ocean air meets slightly warmer land, causing moisture to condense into tiny droplets suspended in the air.

Camanchaca can be dense enough to soak your clothes and reduce visibility to just a few feet. It drifts inland, cloaking hills and valleys before the sun burns it off later in the day.

For a few hours, the landscape feels almost wet, even though not a drop falls from the sky.

Plants and animals have adapted to harvest this fog. Cacti and shrubs catch droplets on their leaves, which then drip down to their roots.

Beetles tilt their bodies to channel fog moisture into their mouths. Fog becomes a substitute water source in an environment where rain is nearly absent.

Camanchaca is a reminder that water can arrive in unexpected forms. While it doesn’t fill rivers or create lakes, it sustains pockets of life that would otherwise vanish.

The desert may be dry, but fog offers a lifeline.

10. Fog oases create “islands” of life

Where camanchaca regularly sweeps across hillsides, something surprising happens: life takes hold. These fog-fed zones are called fog oases or lomas, and they stand out like green islands in an otherwise barren landscape.

The contrast can be startling, with lush vegetation clinging to slopes that seem impossibly dry just a few hundred yards away.

Fog oases support plants specially adapted to pull moisture directly from the air. Their leaves are often covered in tiny hairs or grooves that trap fog droplets.

Water accumulates, drips to the soil, and allows roots to drink. Some species found in these oases exist nowhere else on Earth.

Animals also depend on fog oases. Insects, birds, and small mammals congregate in these patches, creating miniature ecosystems.

The biodiversity can be surprisingly high, with dozens of plant species packed into a small area. Scientists study these oases to understand how life persists under extreme conditions.

Fog oases prove that even in one of Earth’s driest deserts, water finds a way to nurture life. They’re fragile, dependent on the consistent arrival of camanchaca, but they endure.

Walking into a fog oasis feels like discovering a secret garden hidden in plain sight.

11. The Atacama isn’t empty – its biodiversity is just highly localized

At first glance, the Atacama interior looks lifeless. Miles of gravel, salt flats, and rock stretch in every direction with no visible plants or animals.

It’s easy to assume nothing survives here. But look closer, especially near the coast or in fog-touched areas, and biodiversity appears.

Many Atacama species are highly localized, meaning they occupy tiny pockets where conditions allow survival. A hillside catching regular fog might host a dozen plant species, while the valley floor a mile away supports nothing.

This patchy distribution makes the desert’s biodiversity easy to miss if you’re just passing through.

Researchers have cataloged hundreds of plant species in the Atacama, many of them endemic. That means they evolved here and exist nowhere else.

Insects, reptiles, and birds also inhabit specific niches, often tied to fog oases, seasonal streams, or rocky outcrops.

The Atacama challenges our assumptions about deserts. It’s not empty; it’s selective.

Life concentrates where water, even in tiny amounts, can be found. Understanding this localized biodiversity helps scientists appreciate how resilient ecosystems adapt to extreme environments.

The desert may be harsh, but it’s far from dead.

12. Extreme dryness “preserves” the landscape (and even organic material)

Decay requires moisture. Bacteria and fungi that break down organic matter need water to function.

In the Atacama’s hyperarid core, that water simply isn’t available. As a result, decomposition slows to a crawl or stops altogether.

Organic materials can sit exposed for thousands of years without rotting away.

Researchers have discovered plant remains, animal carcasses, and even ancient human artifacts preserved in remarkable condition. Some organic materials are estimated to be several thousand years old, yet they look almost fresh.

The dryness mummifies rather than decomposes.

This preservation extends to the landscape itself. Erosion usually requires water to carve valleys and wear down rock.

In the Atacama, erosion happens at a glacial pace. Landforms remain stable for millennia, creating a frozen-in-time quality.

For scientists, the Atacama is an open-air museum. They study ancient climates, extinct species, and past human activity by examining materials that would have vanished elsewhere.

The extreme dryness is harsh, but it also acts as a preservationist, locking the past in place. Walking through certain areas feels like stepping into a time capsule where history hasn’t faded.

13. Minerals shaped both the scenery and the human story

Beneath the Atacama’s surface lie vast deposits of nitrates and other minerals. These deposits formed over millions of years as chemical processes concentrated salts in the dry soil.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, nitrate mining boomed, transforming the desert into an economic powerhouse.

Mining companies built entire towns in the middle of nowhere. Railways snaked across the desert, carrying ore to coastal ports.

Thousands of workers lived in these remote settlements, extracting wealth from the barren ground. Then synthetic fertilizers were invented, and the nitrate boom collapsed almost overnight.

Ghost towns now dot the Atacama, their buildings eerily well-preserved thanks to the dry climate. Wood doesn’t rot, metal rusts slowly, and paint fades but doesn’t peel.

Walking through these abandoned places feels like touring a museum where time stopped decades ago.

Minerals didn’t just shape human history; they also sculpted the scenery. Salt flats glisten white under the sun.

Colorful mineral deposits streak hillsides. The landscape is a geological showcase, revealing processes that would be hidden or eroded away in wetter climates.

The Atacama’s dryness preserves both natural and human history in striking detail.

14. It’s a “Mars practice field” for space agencies

NASA and other space agencies face a challenge: how do you test Mars equipment when Mars is millions of miles away? The answer is to find the most Mars-like place on Earth.

The Atacama fits that description better than almost anywhere else.

Parts of the desert are so dry and barren that they resemble Martian landscapes. Soil composition, UV radiation levels, and the near-total absence of organic material make the Atacama an excellent analog for the Red Planet.

Rovers, drills, and scientific instruments get field-tested here before heading to space.

NASA’s ARADS project, for example, used the Atacama to practice drilling techniques and search for subsurface life. If instruments can detect microbes in the Atacama’s extreme conditions, they might succeed on Mars.

Engineers and scientists spend weeks in the desert, simulating missions and troubleshooting problems.

The Atacama has become a magnet for researchers studying extremophiles and planetary science. Walking across certain zones, you can almost imagine you’re on another world.

For space agencies, this desert is more than a testing ground; it’s a window into what exploring Mars might actually look like. The Atacama’s dryness makes it the ultimate practice field for interplanetary exploration.