Deep in a wooded valley of southern France, the largest energy experiment in human history is quietly reaching its most delicate stage. Backed by 35 nations and decades of research, this unprecedented project is racing against time, precision, and the limits of physics itself.

Here is a clear breakdown of what is happening and why it matters.

1. A Machine Designed to Recreate the Power of the Stars

Engineers are assembling a reactor capable of replicating nuclear fusion, the same process that powers the Sun. This is not science fiction.

It is a real, physical machine being built piece by piece beneath rural France.

Fusion energy works by forcing hydrogen atoms together under extreme conditions, releasing enormous amounts of energy. Unlike nuclear fission, which splits atoms apart and produces dangerous waste, fusion creates minimal radioactive byproducts.

The challenge has always been making it practical and sustainable.

Building a machine that can contain reactions hotter than the core of the Sun requires materials and engineering never attempted before. Every component must withstand punishing heat, intense magnetic fields, and constant bombardment by high-energy particles.

Success would mark one of humanity’s greatest technological achievements.

If this reactor works as planned, it could prove that clean, nearly limitless energy is within reach.

2. The Project Is Called ITER

The International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, known as ITER, is the world’s largest fusion experiment. While it will not generate electricity for homes, it aims to prove that fusion can work on an industrial scale.

Think of it as a prototype for future power plants.

ITER represents a collaboration among 35 nations, including the United States, China, Russia, Japan, India, South Korea, and the European Union. Each country contributes funding, expertise, and specialized components.

This level of international cooperation is rare in science and engineering.

The project began in 1985 with initial discussions and formal agreements signed in 2006. Construction officially started in 2010.

Since then, thousands of scientists, engineers, and technicians have worked together to turn blueprints into reality.

ITER’s success or failure will shape energy policy and research priorities for decades to come.

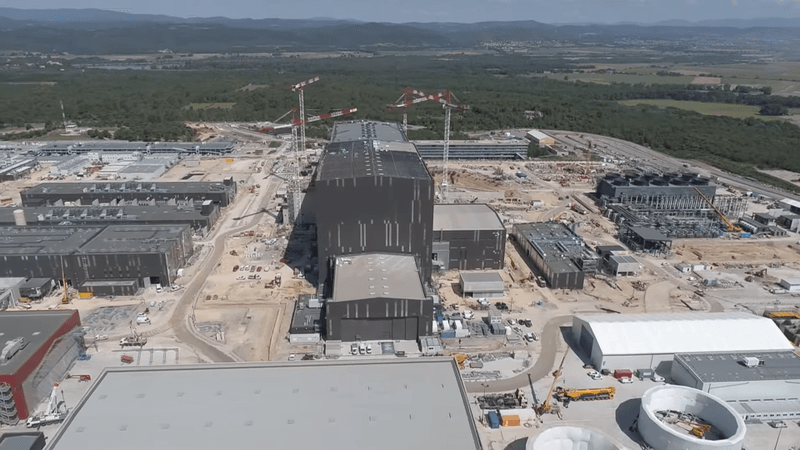

3. Construction Has Entered Its Most Sensitive Phase

Teams have begun lowering massive steel components into the reactor’s core. Each vacuum vessel sector weighs over 400 tons and must be aligned within millimeter-level precision.

Even minor errors could prevent plasma confinement.

The assembly process resembles building a puzzle where each piece weighs as much as a jumbo jet. Specialized cranes and robotic systems position components slowly and carefully.

Workers monitor every movement using lasers and sensors to ensure perfect alignment.

One misalignment could create gaps where superheated plasma escapes, damaging the reactor walls or causing the entire system to fail. There is no room for mistakes.

Engineers often spend weeks preparing for a single lift or installation.

This phase will continue for several years as more components arrive and get installed. Every step brings the project closer to its first test.

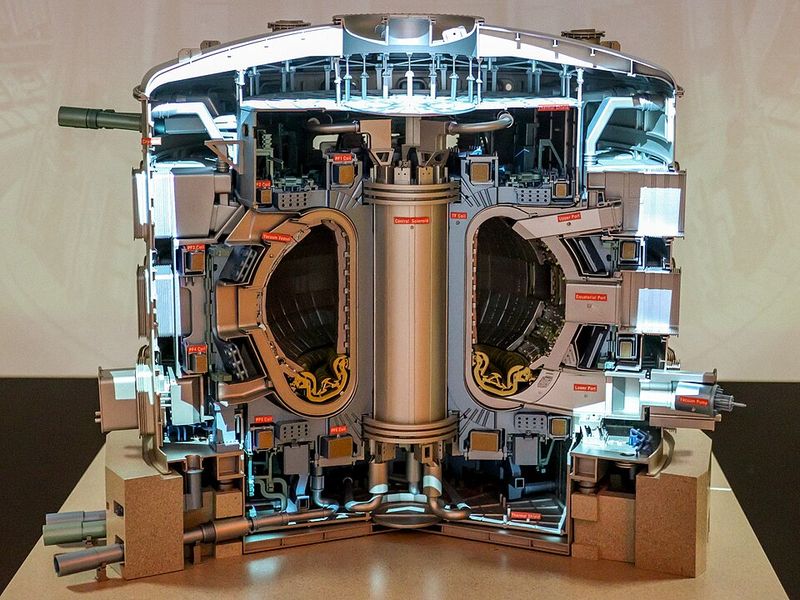

4. The Tokamak Design at Its Ultimate Scale

ITER is based on the tokamak concept, a magnetic confinement system developed in the 1960s by Soviet scientists. Once complete, ITER will be the largest tokamak ever built.

The design uses powerful magnets to hold plasma in a donut-shaped chamber.

Tokamak comes from Russian words meaning toroidal chamber with magnetic coils. The shape and magnetic field work together to keep plasma away from the walls.

Without this confinement, the extreme heat would instantly vaporize any material it touched.

Previous tokamaks were much smaller and used for research. ITER scales up this proven technology to demonstrate that fusion can produce more energy than it consumes.

The reactor chamber stands 30 meters tall and weighs 23,000 tons.

Building at this scale introduces challenges no one has faced before. Every system must work flawlessly under conditions never tested together.

5. Temperatures Hotter Than the Sun

Inside the reactor, hydrogen plasma will reach 150 million degrees Celsius, more than ten times hotter than the Sun’s core. Powerful magnetic coils will keep this plasma suspended without touching the reactor walls.

No material on Earth can withstand direct contact with such extreme heat.

Plasma is the fourth state of matter, created when gas becomes so hot that electrons separate from atoms. At these temperatures, hydrogen nuclei move fast enough to overcome their natural repulsion and fuse together.

This fusion releases energy.

The magnetic field acts like an invisible bottle, holding the plasma in place using forces instead of physical walls. Superconducting magnets generate fields strong enough to confine particles moving at incredible speeds.

The entire system must maintain stability for minutes at a time.

Achieving and sustaining these conditions will prove whether controlled fusion is possible on a practical scale.

6. The Goal: A Fusion Energy Breakthrough

ITER aims to produce 500 megawatts of fusion power from just 50 megawatts of input energy, achieving a performance ratio of Q equals 10. No fusion experiment has ever reached this level.

Getting ten times more energy out than you put in would prove fusion is viable.

Current fusion reactors consume more energy than they produce. Breaking even has been the goal for decades.

ITER’s design should finally surpass that milestone by a significant margin. This would demonstrate that fusion can become a practical energy source.

The 500 megawatts produced would be enough to power about 200,000 homes, though ITER will not connect to the electrical grid. Instead, scientists will study how the reactor performs and use that data to design commercial power plants.

Future reactors could produce even higher ratios.

Success here changes everything we know about energy production possibilities.

7. A Global Engineering Effort

Assembly is led by Westinghouse, working alongside European firms Ansaldo Nucleare and Walter Tosto. Components come from multiple continents, built under different regulatory systems and timelines.

Coordinating this effort requires constant communication and problem-solving across time zones and languages.

Japan manufactures superconducting coils. Europe produces the vacuum vessel sectors.

China delivers critical magnets and power supplies. India contributes cooling systems.

Each part must fit perfectly with components made thousands of miles away by different teams.

Shipping these massive pieces involves custom cargo ships, reinforced trucks, and specially designed transport equipment. Some components take months to manufacture and weeks to deliver.

Delays in one country can impact schedules everywhere else.

Despite these challenges, the collaboration continues. Engineers share solutions and adapt designs as problems arise.

The project proves that nations can work together on ambitious scientific goals.

8. A Revised Timeline Reflects Hard Reality

In July 2024, ITER leadership released a new baseline plan. Deuterium-deuterium plasma operations are now scheduled for 2035.

Full magnetic system testing will happen in 2036. Deuterium-tritium fusion experiments are planned for 2039.

Earlier goals aimed for first plasma by 2018, now delayed by nearly two decades. Technical challenges, funding issues, and coordination problems all contributed to the delays.

Building something this complex and unprecedented takes longer than initial estimates suggested.

Critics argue the delays show fusion energy remains impractical. Supporters counter that groundbreaking science cannot be rushed.

Each setback teaches lessons that improve the final design. The revised timeline reflects a more realistic understanding of what the project requires.

Transparency about delays helps maintain trust and support from member nations. Everyone involved understands the stakes and remains committed to seeing ITER through to completion.

9. Key Design Changes Improve Durability

One major update replaces the original beryllium first wall with tungsten, which better withstands extreme heat and neutron bombardment over long periods. The first wall faces the plasma directly and endures the harshest conditions inside the reactor.

Beryllium was chosen initially for its low atomic weight and good thermal properties. However, testing revealed it would degrade faster than expected under constant neutron exposure.

Tungsten has the highest melting point of any metal and handles neutron damage better.

Making this change required redesigning parts of the reactor and testing new manufacturing techniques. Engineers had to ensure tungsten components could be produced at the required scale and quality.

The switch delays construction slightly but extends the reactor’s operational lifespan significantly.

These kinds of adjustments happen throughout large projects as new information becomes available. Adapting the design now prevents costly failures later.

10. Superconducting Magnets on an Unmatched Scale

ITER required over 100,000 kilometers of superconducting wire, forcing a tenfold increase in global production capacity. Each toroidal field coil stands 17 meters tall and weighs over 300 tons.

These magnets create the powerful fields needed to confine plasma.

Superconducting wire carries electricity with zero resistance when cooled to extremely low temperatures. ITER uses niobium-tin and niobium-titanium alloys that become superconducting near absolute zero.

Liquid helium keeps the magnets cold enough to function properly.

Manufacturing enough wire required building new factories and training specialized workers. The coils themselves are wound with incredible precision, then encased in steel structures.

Installing them involves lifting and positioning these massive components without damaging delicate superconducting materials.

The magnet system represents one of the most expensive and technically demanding parts of the entire project. Without it, plasma confinement would be impossible.

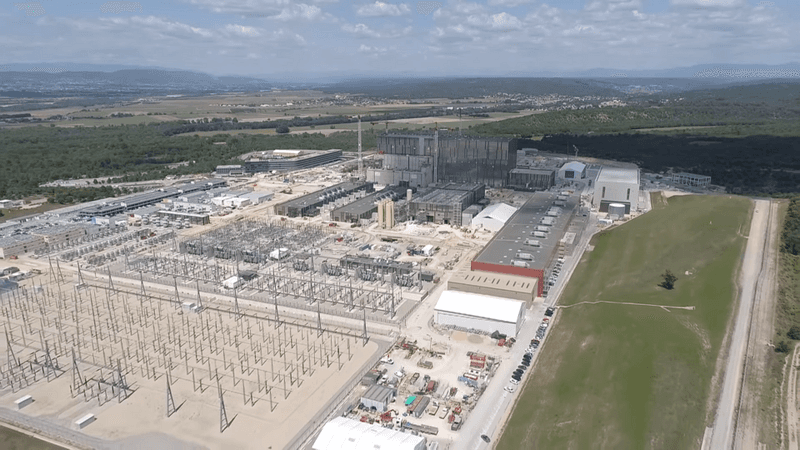

11. Extreme Logistics Made It Possible

To transport massive components, engineers built a 104-kilometer specialized transport route capable of handling loads up to 900 tons. Components are moved at night using remote-controlled platforms.

The route winds through narrow villages and steep hillsides in southern France.

Roads had to be widened and reinforced. Bridges were strengthened or rebuilt.

Power lines were raised or buried to allow oversized cargo to pass underneath. Local residents were consulted and compensated for disruptions.

Planning each transport took months of preparation.

The transport vehicles move at walking speed, guided by operators using joysticks and cameras. Police escort convoys and manage traffic.

Each journey can take hours or even days depending on the component size. Timing is carefully coordinated to minimize impact on daily life.

This logistical achievement demonstrates the extraordinary effort required to build something at ITER’s scale in a developed area.

12. Why ITER Matters for the Future of Energy

ITER will not power homes, but it could pave the way for DEMO, a future commercial fusion plant. Success would mean a near-limitless, carbon-free energy source with minimal waste and no risk of meltdown.

Fusion fuel comes from water and lithium, both abundant resources.

Unlike fossil fuels, fusion produces no greenhouse gases. Unlike current nuclear fission, it generates far less radioactive waste and cannot experience runaway reactions.

A fusion plant could operate safely near populated areas without catastrophic risk. The fuel supply would last for thousands of years.

DEMO is planned to begin construction in the 2030s if ITER succeeds. Commercial fusion plants could start operating by the 2050s.

These facilities would provide steady, reliable power without dependence on weather like solar and wind energy.

ITER represents humanity’s best chance to solve the energy crisis while protecting the planet for future generations.