On a small island in Southeast Asia, daily life runs on a different rhythm. Homes are busy, decisions are made quickly, and the people holding everything together are usually women.

It’s not a trend, and it’s not a slogan. It’s what happens when work pulls a huge share of the men far from home for months or years at a time.

Over time, that distance changes more than schedules. It shifts responsibilities, reshapes family roles, and turns waiting into a way of life.

Women manage the money, raise children, protect customs, and keep communities steady while loved ones earn income far away.

What makes this place fascinating is that its story isn’t just about one community. It’s about how migration and economics can quietly rewrite an entire culture, without anyone voting on it or planning it.

And the reasons behind it are more complex than they first appear.

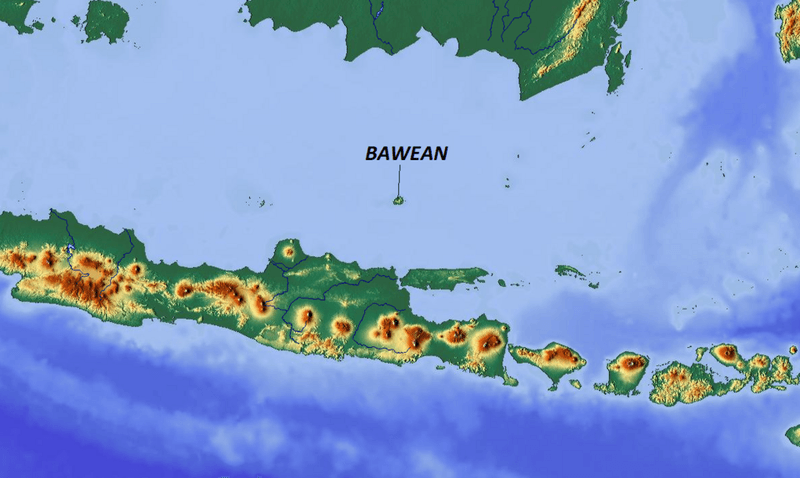

1. A Real Indonesian Island Floating in the Java Sea

Bawean isn’t folklore. It sits about 150 kilometers north of Surabaya in East Java, far enough from the mainland that life moves at its own rhythm.

The Java Sea surrounds it on all sides, giving the island a sense of isolation that modern Indonesia rarely offers anymore.

When you visit, you’ll immediately noticed how quiet everything feels compared to Java’s crowded cities. No traffic jams.

No honking motorbikes every five seconds. Just waves, wind, and the occasional fishing boat chugging past the shore.

The remoteness isn’t just geographical. It’s cultural too.

Bawean operates on a different clock, shaped by decades of men leaving and women staying. That distance from the mainland created space for unique traditions to flourish, traditions that might have faded elsewhere under the pressure of modernization.

Getting there requires planning. Ferries run from Gresik, and small planes occasionally connect the island to Surabaya.

The journey itself filters out casual tourists, leaving Bawean largely untouched by the crowds that swarm Bali or Lombok. For travelers seeking authenticity over Instagram backdrops, this island delivers.

2. Men Leave for Paychecks, Not Police Orders

No law forces men off Bawean. No government policy exiles them.

The “must” in “men must leave” comes from empty pockets and limited options. Jobs on the island pay poorly or don’t exist at all, pushing men toward Malaysia, Singapore, and other countries where wages can support entire families back home.

Economics wrote the script here, not politics. When a man can earn in one month abroad what would take six months on Bawean, the choice becomes obvious.

Tradition reinforced the pattern over generations, turning temporary migration into a rite of passage for young men.

Some leave for a year. Others stay away for five or ten.

The separation strains marriages and reshapes childhoods, but it also keeps roofs over heads and rice in pots. Women wait, manage, and adapt while their husbands send money from factories, construction sites, or ships.

This isn’t unique to Bawean. Millions of Indonesians work abroad as migrant laborers.

But few places have seen such a concentrated, sustained exodus that it flipped the gender ratio and earned a nickname. The island’s story is Indonesia’s labor migration writ small and intimate.

3. The Math Behind the “Island of Women” Label

Numbers tell the story. Reports suggest women make up roughly 77 percent of Bawean’s resident population, a ratio dramatic enough to earn the island its Pulau Putri nickname.

That translates to three women for every man actually living there day to day.

The calculation only counts people physically present, not those working abroad. If you included absent men in the total, the ratio would balance out.

But lived reality matters more than census data, and the lived reality is that women dominate public spaces, markets, schools, and community gatherings.

Walking through a village gets you noticing how few adult men appear anywhere. Women chat outside shops.

Women herd kids to school. Women repair fences and hauled water.

The absence becomes visible only through its effects.

This gender imbalance isn’t static. It fluctuates with economic conditions abroad and holidays when men return.

During Ramadan or major festivals, the ratio temporarily shifts as workers fly home. But for most of the year, Bawean remains a place where women outnumber men by a wide margin, shaping everything from social dynamics to local politics.

4. Not a Tiny Village Despite the Mystique

Headlines love framing Bawean as some tiny, forgotten outpost. Reality disagrees.

The 2020 census recorded around 80,000 residents, with later estimates pushing that number higher. That’s bigger than many small cities.

The “mysterious island” label sells clicks but obscures scale. Bawean has schools, clinics, government offices, and functioning infrastructure.

It’s not a deserted sandbar with three huts and a palm tree. Tens of thousands of people call it home, even if many men are temporarily elsewhere.

Size matters because it changes the narrative. This isn’t a quirky anomaly affecting a handful of families.

It’s a systemic pattern shaping an entire regional population. The migration phenomenon touches nearly every household, creating ripple effects through education, health care, and local governance.

Population density varies across the island. Some villages cluster tightly, while others spread across hillsides.

The main towns feel lively during daylight hours, with markets, mosques, and shops serving daily needs. At night, things quiet down fast, but that’s true for much of rural Indonesia.

Bawean isn’t empty. It’s just different.

5. Women Become the Household CEOs

Forget traditional gender roles. When your husband works 2,000 miles away, you become the decision maker by default.

Women on Bawean handle everything: raising kids, budgeting remittances, fixing broken roofs, negotiating with teachers, and planning long-term investments.

Women described themselves as “the manager, the accountant, and the security guard.” Their husbands send money monthly from Malaysia, but they decide how to spend it. Education for the kids?

Their call. New fishing boat?

They ran the numbers.

This responsibility builds competence fast. Women learn financial management, conflict resolution, and problem-solving skills out of necessity.

They can’t wait weeks for their husbands to weigh in on urgent matters. Life demands immediate answers, so they provide them.

The shift empowers some women and exhausts others. Juggling every household role leaves little time for rest or personal pursuits.

But it also proves what women can accomplish when given full authority. Bawean’s women aren’t just surviving their husbands’ absences.

They’re running complex operations that would overwhelm many people regardless of gender. The island functions because they do.

6. Remittances Function as Invisible Infrastructure

Money from abroad doesn’t just pay for rice and school uniforms. It builds houses, funds weddings, and shapes the island’s entire standard of living.

Remittances act like invisible infrastructure, supporting Bawean’s economy more reliably than any government program.

Walk through any village and you’ll spot homes built with overseas earnings. Newer construction stands out against older structures, marking families with workers abroad.

Education choices also reflect remittance income, with some families affording better schools or tutors because dad earns in ringgit or dollars.

This dependence creates a feedback loop. Kids grow up watching fathers leave and return with money.

They internalize the message that success means working abroad. When they reach adulthood, many follow the same path, perpetuating the cycle across generations.

Economists call this “remittance dependency,” and it worries development experts. What happens if foreign labor markets tighten?

What if host countries restrict migration? Bawean’s prosperity hangs on forces beyond local control, making the island vulnerable to global economic shifts.

For now, the money keeps flowing, but the system’s fragility lurks beneath the surface.

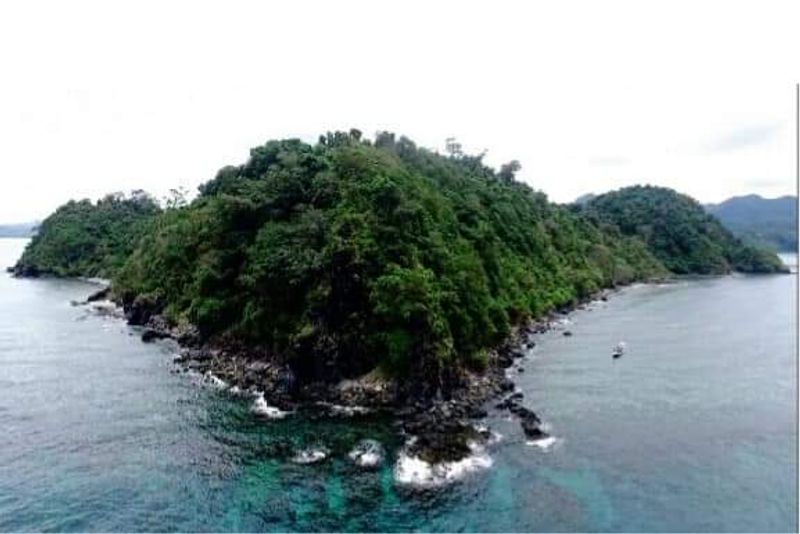

7. Volcanic Hills Perfect for Slow Exploration

Bawean rose from volcanic activity, leaving behind a hilly, forested landscape that rewards patient exploration. A main road loops much of the island, but the real beauty hides along smaller paths winding through green hills and quiet villages.

Bicycles work better than cars here. The island’s scale suits pedaling, and the slower pace lets you actually see things: kids playing in yards, women tending gardens, chickens scattering across dirt paths.

Rushing misses the point entirely.

You can bike uphill to a viewpoint overlooking the coast. The climb will hurt your legs, but the top offers views across forest canopy to the Java Sea beyond.

No other tourists. Just wind and bird calls and the occasional motorbike putting past below.

The terrain isn’t flat or easy. Hills dominate the interior, and some roads turn steep enough to force walking.

But that difficulty filters out casual visitors, preserving a sense of discovery. Bawean rewards effort with solitude and scenery that hasn’t been photographed to death.

For travelers who enjoy destinations that demand something from them, this island delivers perfectly.

8. Getting There Requires Commitment

Reaching Bawean involves either a ferry from Gresik or a small aircraft connection through Surabaya. Neither option is quick or frequent.

The ferry takes several hours and doesn’t run daily. The plane seats maybe a dozen people and books up fast during holidays.

This limited access explains why Bawean stays under the radar. Bali has international airports and endless flights.

Lombok connects easily from multiple cities. Bawean makes you work for it, which keeps crowds away but also limits economic development.

If you take the ferry, you’ll immediately understand why tourism hasn’t exploded here. The boat rocks hard enough to turn stomachs, and the schedule meant arriving late or leaving early with no flexibility.

Convenience isn’t Bawean’s selling point.

Yet that difficulty creates value for certain travelers. If you want unspoiled, unfiltered Indonesia, the hassle pays off.

You’ll share the island with locals, not tour groups. Restaurants serve food for residents, not tourists.

The experience feels authentic because it is. Bawean hasn’t been packaged and polished for foreign consumption.

It simply exists, take it or leave it.

9. Home to a Deer Found Nowhere Else

Bawean’s most famous resident isn’t human. The Bawean deer, scientifically named Axis kuhlii, lives only on this island and nowhere else on Earth.

Conservation groups list it as Critically Endangered, with fewer than 300 individuals surviving in the wild.

These deer are small, about the size of a large dog, with reddish-brown coats and white spots. They stick to forested areas, avoiding human settlements when possible.

Spotting one requires luck and patience, preferably with a local guide who knows their habits.

Habitat loss threatens their survival. As Bawean’s human population grows, forests shrink.

Agriculture expands, roads cut through habitat, and the deer lose ground. Conservation efforts exist but struggle with limited funding and competing land-use pressures.

The deer’s rarity makes it symbolically important. It represents what makes Bawean unique beyond the gender ratio story.

This island harbors biodiversity found nowhere else, a reminder that isolation preserves more than cultural traditions. Protecting the Bawean deer means protecting the forests, which benefits everyone.

But economic pressures make conservation difficult when families need land and income. The deer’s fate hangs in the balance.

10. Wildlife Isn’t Just Cute Postcard Material

Bawean’s forests hold more than adorable deer. Reports mention reptiles, including venomous species, plus forest wildlife that ranges from harmless to potentially dangerous.

Nature here demands respect, not just Instagram photos.

Snakes live in the underbrush. Some are harmless.

Others aren’t. Locals know which is which, but visitors often don’t.

Walking off-trail without a guide is asking for trouble. The island’s isolation means medical facilities are basic, and serious bites require evacuation.

Tourists have reported seeing lizard, easily five feet long, sunning itself near a stream. Beautiful creature, but they kept their distance.

Wild animals aren’t petting zoo residents. They’re wild, with all the unpredictability that implies.

This reality adds edge to Bawean’s appeal. It’s not sanitized or safe in the way resort islands are.

You’re visiting functioning ecosystems where humans are guests, not masters. That authenticity attracts some travelers and repels others.

If you want guaranteed safety and controlled experiences, stick to Bali. If you’re okay with a little risk in exchange for genuine wilderness, Bawean delivers.

11. A Diaspora Story Spanning Generations

Baweanese communities exist far beyond the island itself. Singapore and Malaysia host longstanding populations of Boyanese (another name for Baweanese people), with migration histories stretching back generations.

These diaspora networks shape life on Bawean as much as anything happening locally.

Family connections abroad provide job leads, housing, and support for new arrivals. A young man leaving Bawean for the first time often stays with relatives who left years earlier.

This system reduces risk and maintains cultural continuity across borders.

The diaspora also sends money, advice, and ideas back home. Trends in Malaysia influence Bawean fashion and consumer preferences.

Success stories from Singapore inspire kids to study harder. The island and its scattered population remain connected through constant communication and circular migration.

Scholars describe this as transnational community, where identity and belonging span multiple countries. Baweanese people don’t just live on an island.

They occupy a network stretching across Southeast Asia, with Bawean as the symbolic and emotional center. Understanding the island requires understanding the diaspora.

They’re inseparable parts of the same story, written across oceans and generations.

12. Not Anti-Men, Just Pro-Survival

Sensational headlines make Bawean sound like some matriarchal society that exiled men. Wrong.

The “Island of Women” label describes an economic survival strategy, not gender politics. Women dominate because men are elsewhere earning money to support those same women and children.

No one celebrates the separation. Wives miss husbands.

Kids grow up without fathers present. Men endure loneliness and harsh working conditions abroad.

The system exists because alternatives are worse, not because anyone prefers it this way.

Women’s central role emerged from necessity, not ideology. They keep families stable, culture alive, and daily life functioning because someone has to.

The arrangement empowers women in some ways while burdening them in others. It’s complicated, like most real-life situations.

The most important takeaway? Bawean’s story is about resilience, not gender conflict.

Families adapt to economic realities beyond their control, finding ways to survive and sometimes thrive despite separation. Women become leaders because circumstances demand it.

Men leave because staying means poverty. Together, they maintain a community across distance, held together by remittances, phone calls, and the hope of eventual reunion.

That’s survival, pure and practical.