Deep beneath one of the world’s most studied cities, archaeologists have uncovered something that is changing the way we understand ancient Jerusalem. A massive rock-cut structure in the City of David appears to be a 3,000-year-old defensive moat from the First Temple period.

The find connects physical evidence to descriptions found in biblical texts, offering a rare bridge between archaeology and ancient writing. Here are the verified facts behind this remarkable discovery.

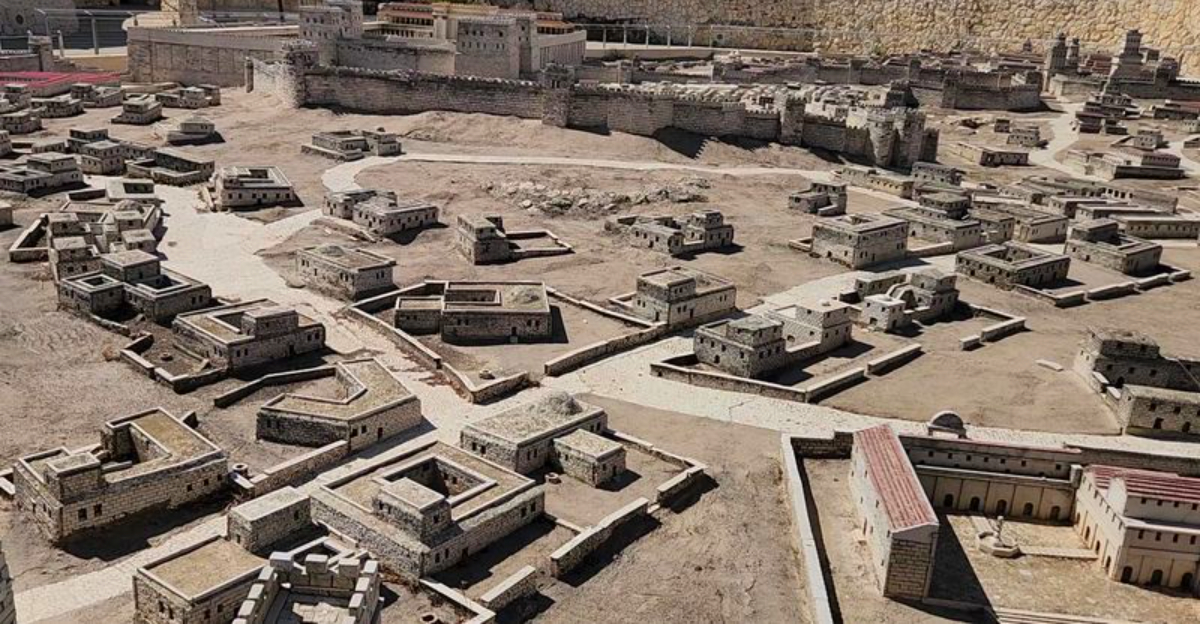

The Structure Was Found in the City of David

Just south of Jerusalem’s famous Old City walls lies one of the most historically rich patches of land on Earth. The City of David has been the focus of serious archaeological research for decades, drawing teams from universities and institutions around the world.

This excavation site sits on a narrow ridge that ancient inhabitants chose for its natural defenses. Researchers have uncovered layers of history here, from pottery shards to monumental architecture, each find adding detail to a complex story.

The discovery of this rock-cut structure adds a major new chapter. Its location in the City of David places it at the very heart of debates about ancient Jerusalem’s size, power, and organization during one of the most discussed periods in all of human history.

It Dates to the First Temple Period

Three thousand years is almost impossible to picture, yet archaeologists have methods to anchor discoveries firmly in time. Pottery styles, stratigraphic layers, and radiocarbon dating all help researchers assign approximate dates to what they find underground.

The structure aligns with the First Temple period, traditionally placed between the 10th and 6th centuries BCE. This era is associated with the reigns of kings like Solomon and David in biblical accounts, making any physical find from this time especially significant to historians and religious scholars alike.

Dating a discovery this old with confidence requires cross-referencing multiple lines of evidence. When those lines all point to the same era, researchers gain real confidence in their conclusions.

The convergence of evidence here makes the First Temple period dating particularly compelling and hard to dismiss.

The Feature Is a Rock-Cut Channel

What makes this structure genuinely unusual is how it was made. Rather than being built up from stacked stones or mudbrick, the channel was carved directly into the natural bedrock beneath the city.

That distinction matters enormously to archaeologists trying to understand its purpose.

Rock-cut features require different tools, different planning, and a different kind of workforce than constructed walls. The precision involved in cutting a long, wide, and deep trench into solid limestone tells us something important about the people who made it.

Carved bedrock also preserves differently than built structures. It cannot collapse the same way walls do, which is partly why portions of this channel survived thousands of years underground.

The sheer durability of rock-cut architecture is one reason researchers were eventually able to recover enough of it to understand its original form and function.

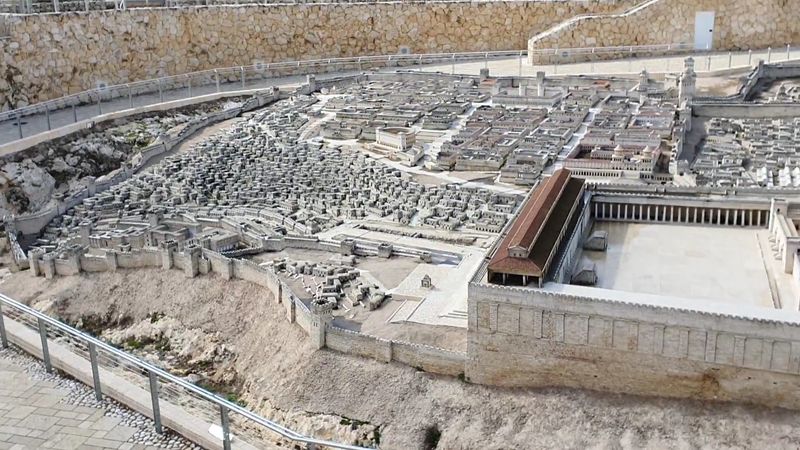

It Separates Key Areas of the Ancient City

Geography and city planning go hand in hand, especially in the ancient world. Researchers studying the channel’s position found that it physically divided two distinct zones within ancient Jerusalem.

On one side sat residential neighborhoods; on the other stood the city’s political and religious core.

That kind of spatial separation was not accidental. Ancient city planners understood the value of controlling movement between everyday living spaces and the seat of power.

A physical barrier between the two would have reinforced social hierarchies and protected the most important buildings.

Finding evidence of deliberate urban zoning in a 3,000-year-old city challenges older assumptions that early Jerusalem was loosely organized. The channel’s placement suggests careful thought about how the city functioned as a whole, pointing to a level of administrative planning that many scholars previously doubted existed this early.

It Was Previously Partially Known

Archaeological discoveries rarely appear out of nowhere. Portions of this channel had actually surfaced in earlier excavations, but the pieces never quite fit together into a clear picture.

Without understanding the full extent of the feature, researchers could not agree on what it was or why it existed.

Earlier theories ranged widely. Some scholars suggested the cuts were related to water management, while others thought they might be quarry marks left behind when builders extracted stone for construction projects elsewhere in the city.

Partial knowledge can sometimes be more confusing than no knowledge at all. When only fragments of a large structure are visible, it is easy to misread their purpose.

The history of this particular feature is a good reminder that archaeological interpretation improves steadily over time as more evidence comes to light and new excavation techniques are applied.

New Excavations Revealed Its Full Scale

Recent fieldwork changed everything. New excavations exposed the channel’s true depth, width, and continuous alignment in a way that earlier digs simply had not managed.

Seeing the full picture finally allowed researchers to understand what they were actually looking at.

Modern excavation techniques, including precise mapping tools and improved stratigraphic analysis, helped the team document the feature systematically. Every meter of the channel was recorded, photographed, and analyzed before any conclusions were drawn.

The scale turned out to be far greater than anyone had previously assumed. A feature that once seemed like a minor cut in the rock was revealed to be a massive, intentionally engineered structure running a considerable distance through the bedrock.

That shift in understanding from small and ambiguous to large and purposeful fundamentally changed how archaeologists interpreted everything else around it at the site.

It Appears to Have Served a Defensive Purpose

Once the full scale of the channel became clear, its purpose started to come into focus. Archaeologists considered several possibilities, weighing the structure’s size, placement, and engineering against what is known about ancient defensive architecture in the region.

A drainage channel would not need to be this wide or this deep. A quarry would typically show less uniform cutting and would not follow the city’s edge so precisely.

The evidence kept pointing in one direction: this was a defensive moat, designed to slow or stop attackers from reaching the city’s most important areas.

Moats were a well-documented defensive strategy in the ancient Near East. Cutting one directly into bedrock rather than flooding a ditch with water created a permanent, maintenance-free barrier.

For a city without easy access to large quantities of water for flooding, a dry rock-cut moat was a practical and effective solution.

The Moat Would Have Restricted Movement

A moat does more than stop a frontal assault. Its real power lies in controlling where people can and cannot go.

By positioning the channel strategically, ancient planners forced anyone entering or leaving the city’s core to pass through specific, easily monitored points.

Think of it like a fence around a schoolyard. The fence does not just keep people out; it channels everyone through the main gate where they can be seen and counted.

The same logic applied here, but the stakes were much higher than attendance records.

Controlling access to the political and religious center of a city was a matter of security, ceremony, and power. Visitors would have approached through designated routes, making it easier for guards to screen them.

That kind of controlled movement is a hallmark of organized, hierarchical societies with something valuable to protect.

It Demonstrates Advanced Engineering

Carving a large moat directly into solid limestone is not a weekend project. It required a workforce that was organized, fed, and directed over an extended period of time.

The labor involved points to a governing authority capable of mobilizing large numbers of people toward a single long-term goal.

Planning the channel’s route, depth, and width would have required surveyors or at least experienced craftsmen who understood how to read terrain and anticipate the structural behavior of rock as it was cut. Getting those calculations wrong could have wasted enormous effort.

The quality of the engineering visible in the channel’s surviving walls suggests this was not improvised work. Someone designed it, someone oversaw it, and many people executed it.

That chain of command implies a level of civic organization in First Temple period Jerusalem that gives archaeologists and historians a great deal to think about.

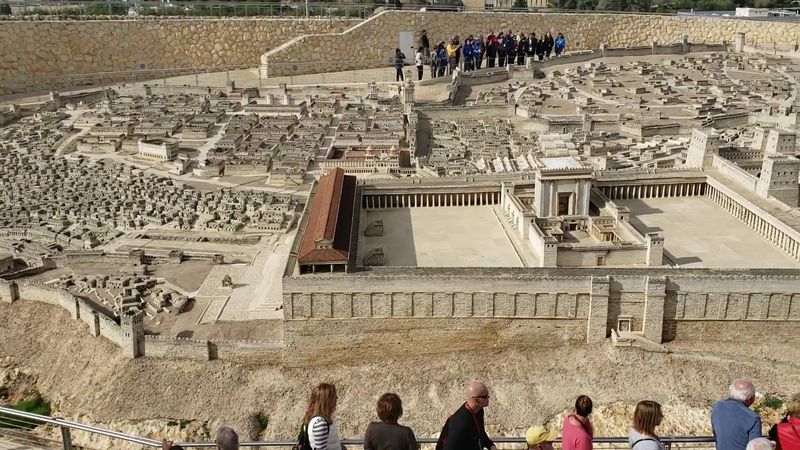

It Supports Evidence of Fortified Jerusalem

For years, some scholars argued that ancient Jerusalem was a modest, lightly defended settlement rather than the powerful fortified city described in certain historical and religious texts. Each new discovery at the City of David pushes back against that view a little more firmly.

Previous finds, including walls, gates, and administrative buildings, already suggested a city with real organizational complexity. The moat adds another layer of evidence, literally and figuratively, that Jerusalem during the First Temple period had serious, intentional defenses.

Accumulating physical evidence matters in archaeology because no single find proves everything on its own. But when a moat, walls, gates, and administrative structures all appear together in the same location and the same time period, the overall picture becomes hard to argue with.

Fortified Jerusalem is no longer just a textual claim; it is increasingly a documented archaeological reality.

Scholars Have Long Debated Its Purpose

Academic debates about this feature have been going on for years. Researchers looking at the same partial evidence came to very different conclusions, which is actually a healthy sign in a field where overconfidence can lead to serious interpretive mistakes.

Water management was one popular theory. Ancient cities needed to move rainwater and waste efficiently, and rock-cut channels were sometimes used for exactly that.

Stone quarrying was another competing explanation, since Jerusalem’s builders constantly needed raw material.

What the new excavations did was provide enough data to test each theory seriously against the physical evidence. When the full dimensions and positioning of the channel were mapped, the water management and quarry theories struggled to hold up.

The defensive moat interpretation fit the evidence more completely and consistently, which is ultimately how archaeological debates get resolved: not by authority, but by evidence.

It Aligns With Descriptions of Defensive Features in Biblical Texts

Biblical texts describe ancient Jerusalem as a fortified city with walls, towers, and defensive structures protecting its political and religious center. For a long time, matching those descriptions to physical evidence was more hope than reality for archaeologists working the site.

The moat does not prove any specific biblical passage word for word. Archaeology rarely works that neatly, and responsible researchers are careful not to overstate connections between texts and physical finds.

What the channel does offer is a chronological and structural alignment that is genuinely meaningful.

A large defensive feature, dated to the right period, positioned in the right place, and engineered to protect the city’s core fits comfortably alongside textual descriptions of a fortified Jerusalem. That kind of correspondence between the written record and the physical record is exactly what archaeologists work toward, and finding it here represents a significant step forward in understanding this ancient city.