You wouldn’t expect a Chrysler Turbine Car to hide beside a quiet canal off Lake St. Clair, but that’s exactly what you’ll find at the Stahls Motors and Music Experience in New Baltimore, Michigan. Tucked behind a modest facade on North Bay Drive, this unique museum blends rare vintage automobiles with perfectly restored player organs and mechanical music machines.

Open the door and the temperature shifts, the air faint with oil and wax as a Wurlitzer organ breathes to life. Every step carries you past cars and machines that feel pulled from another era – except here, they still run, sing, and shine.

Finding the Door: First Steps Into the Warehouse of Time

Pull off Gratiot, wind through a low industrial strip, and you will second guess the address until 56516 N Bay Drive appears. The building looks like any warehouse, which feels like part of the magic.

Step inside and the temperature dips a few degrees, crisp with the scent of carnauba wax, cool steel, and old varnish.

To your left, neon signs glow like bottled sunset. A docent at a small podium nods hello, then slips in a detail you will want to remember: certain cars still run.

Your shoes echo on polished concrete that mirrors fenders and chrome; right away you learn to walk softly, like you are inside a cathedral, but built for pistons.

Do not rush. Let your eyes adjust to the soft pools of light that isolate silhouettes, each car with a little stage.

The first whisper of the Wurlitzer organ drifts from deeper in the hall, a warm exhale through wood and brass. The space totals 45,000 square feet, but it feels bigger because time moves differently here.

Museum hours skew friendly and specific: free on Tuesday afternoons, first Saturdays, and most Thursdays in summer, barring the third. That means pacing yourself matters.

If you love an open loop, leave a few placards unread on purpose so you have a reason to circle back when the organ wakes up.

The Wurlitzer Breathes: When Music Turns the Lights in Your Head

Sound happens first as a vibration in the ribcage. The Wurlitzer theater pipe organ does not merely play melodies, it pressurizes the air until the room becomes an instrument.

Stop tabs flicker like candy buttons, and somewhere behind walls, ranks of pipes answer with voices that swing from church to carnival.

You feel it in the floor, a velvet push that softens your knees. The organist, palms wide, feathers the keys and cranks a tremulant that turns light into liquid.

Every car looks shinier when the chord swells, as if chrome were invented for this soundtrack.

Docents measure time by songs. When the last note hangs, somebody always whispers that the instrument outlived the movie palaces it once powered.

Here, among hood ornaments and deco fonts, it finds natural company in machinery designed to move humans without speaking.

If you are lucky, a roll of paper on an orchestrion starts punching out ragtime nearby. The instruments converse across the room, machine to machine, reminding you that automation once wore mahogany and velvet.

Keep an ear tuned during the first Saturday sessions; music cues often precede a engine demo, and that handoff from reed to exhaust feels like a tightrope walk between two golden ages.

Art Deco in Steel: Hood Ornaments That Tell You Secrets

Move closer than you usually would. The light here rewards nerve, slicing along a winged goddess where chrome meets shadow.

You can see a thumbprint swirl from some forgotten polishing session, sealed into the metal like a quiet signature.

Art Deco was not subtle, and neither are these mascots. They extend the car’s imaginary speed, frozen leaps over radiators that still smell faintly sweet from coolant.

The placards speak dates and designers, but the real story rests in the unscuffed edges, proof someone cared more about preservation than attention.

A 1930s bird flares its wings, split like piano keys, and you will swear you hear a whispering whoosh. Another figure tilts forward with a gymnast’s certainty, knees hidden inside geometry.

You realize that style once existed to pull future closer, not to shout about it.

Photograph with restraint. Do not lean.

A docent might slide over to point at a hairline casting seam, then tell you which sculptor also designed perfume bottles. That crosscurrent of machine and luxury sets the tone for everything else here: speed imagined by artists who also cared about touch, weight, and how a gloved hand meets cold chrome at 1 PM on a Tuesday.

Tucker 48: The Car That Blinked at the Future

The Tucker 48 sits low and smooth, like it knows the lawsuits are over and it finally gets to rest. Stand at the nose and let your eyes settle on the cyclops headlight, a wink aimed right down the centerline of American car history.

Doors shut with the modest thud of a midcentury front door, not a vault.

Placards mention safety glass, perimeter frame, and a rear engine that suggested common sense while the industry looked away. You can picture Preston Tucker pitching features that would not be mainstream for decades.

The bodywork wears a light that rolls like water over lake stones, and the color reads different under every spotlight.

There is a soft drama to how visitors move around it, slower than at the muscle cars, closer than at the Duesenberg. People ask each other if it really steered the headlight.

Someone always leans in to peer through the rear glass, then steps back as if they caught the car thinking.

Ask a docent about the film and the real court transcripts if you like rabbit holes. The answer usually includes a quiet shrug that says vision meets timing, and timing wins.

Then you will hear a kid say it looks modern, which tells you Tucker did not miss his shot, he fired early and the world kept the echo.

Duesenberg Model J: The Weight of Quiet Money

Stand beside a Duesenberg Model J and time goes formal. The fenders arc like practiced gestures, and the hood stretches farther than your first apartment.

Chrome pipes march from the engine bay like polished ribs, a whisper that power once wore tuxedos.

Everything feels heavy here, from door handles to the expectation. You can almost hear a valeted cough on Fifth Avenue, a doorman watching the meter of a Great Depression that did not touch everyone equally.

The coachwork carries small flourishes that reward a patient scan: a hinge that looks beveled by a jeweler, a taillamp bracket with unearned confidence.

A docent may point to the supercharger story, or the horsepower numbers that turned adjectives into understatements. People nod like the figures make sense, but what lands is the poise.

Even parked, the car seems to understand arrivals.

There is context on the wall for the era that birthed it, the uneven calculus of opulence during scarcity. It deepens the room, nudging you to look back at simpler dashboards nearby.

On your way out of the Duesenberg’s orbit, catch the reflection of Art Deco lettering in the lacquer and ask yourself whether luxury is louder now or just thinner.

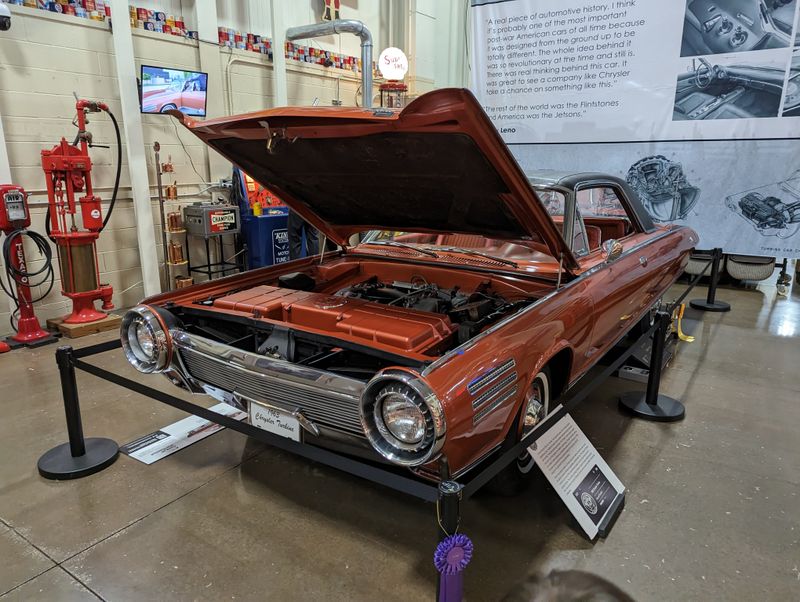

Chrysler Turbine Car: The Orange That Hums Different

It sits like a prototype that somehow outran the trapdoor. The Chrysler Turbine Car glows in that burnished orange, a color that feels both government issue and sci fi.

Walk to the rear and the exhaust ring tells you this was a bet placed on a different kind of breath.

Engines purr, turbines whine, and even standing still you can hear the idea. The placard notes that only nine survive, with two in private hands, and somehow this fact compresses the room.

You find yourself circling, searching for the piece that explains why we did not all commute on jetwash.

Ask how it sounded on demo days and people will describe a distant airplane idling at shoulder height. There is a disciplined restraint to the design, as if Chrysler wanted to look normal while renegotiating physics.

Seats, dash, switchgear: all midcentury calm wrapped around an engine that would rather live on a runway.

That hum still pulls visitors who heard it long ago. For everyone else, the absence of noise becomes a second soundtrack, a memory others lend you.

The car proves the museum’s central thesis: innovation is rarely loud at the start, it just changes the color of the air and waits for you to notice.

Engines That Still Wake Up: Live Demonstrations

Schedules here are friendly but elastic, which makes the engine demos feel like you won a raffle. A docent lifts a rope, a small crowd folds in, and suddenly a hand twists a key that smells faintly of brass.

The starter chatters, fuel finds spark, and the room inhales at once.

It is not theatre. Belts twitch, fans blur, and a cough becomes a steady heartbeat.

Exhaust wings a soft blue ribbon that drifts toward the rafters, fading under the HVAC like a secret exhaled and caught.

People turn into kids as gauges climb. You will, too.

There is a distinct dignity to machines that still do their job after nearly a century, an earned right to be noisy for a minute on a Tuesday.

Practical note: ask staff about demo windows right when you arrive. Timing is everything, and first Saturday sessions stack the odds.

Stay near the cars with drip pans and fresh tire chalk; those quiet clues often predict which one might wake, and nothing feels better than being close enough to feel that first shiver through the floor.

Talking With Docents: Conversations That Change the Room

Find the person with the lanyard and the easy stance. Ask one sincere question and you will get three stories, one technical and two human.

Docents here carry timelines in their pockets, plus torque specs they can recite like birthdays.

One might tell you which car was a veteran’s first ride home after deployment, then segue into why that carburetor hates ethanol without sounding scoldy. Another will point at a dash knob and trace a designer’s hand across decades, from bakelite to brushed aluminum.

These are not lectures so much as tuned engines of memory.

Bring one fresh fact to prime the pump. Mention the collection’s 45,000 square feet, or that it ranks 4.9 stars online, and watch eyes light.

You will get a corrective detail that sharpens the number, because context is the local currency.

Conversations change how you see the cars. A Duesenberg turns into a family argument about maintenance, a Tucker becomes a courtroom drama with sanity on the stand.

Leave time for these detours, and if you can, circle back to the same docent after the Wurlitzer set; music loosens stories the way warm oil loosens old bolts.

Autos for Autism and Veterans Day: When the Community Shows Up

Calendar events change the museum’s temperature. Autos for Autism turns the floor into a fundraiser with heart, where rare cars park beside handmade posters and kids trace fenders with their eyes.

Veterans Day opens the doors wider, and the sound of the organ lands different when the crowd stands still for a moment.

People dress up a little, wearing club jackets with stitched history. You will see handshakes that mean more than hello, and a few quiet corners where someone finally sits in a seat they remember from a busier decade.

Cars get framed by people who understand them in their bones.

These days compress the distance between collection and community. Admission is often free already, but the donation boxes grow full and the docents move fast, ferrying stories as if time were a warm pie that needs slicing before it cools.

There is gratitude in the air, unshowy and practical.

If you want the deepest version of this place, plan around one of these dates. Check the site early.

It fills fast, and you will want room to stand back when the Wurlitzer hits a chord that turns conversation into shared silence, then applause that sounds like wrenches on a well kept bench.

Planning Your Visit: Hours, Routes, and Smart Timing

Put the address in your notes: 56516 N Bay Dr, New Baltimore, MI 48051. The museum opens to the public free on Tuesday afternoons, first Saturdays, and most Thursdays in summer except the third.

Doors at 1 PM on Tuesdays mean you can grab an early lunch, beat the first rush, and park without hunting.

From I-94, the last miles feel local in a good way. Lake St. Clair air rolls across flat lots, and the building hides in plain sight beside low water and quiet side streets.

Bring a light jacket; the climate stays museum cool, and you will be standing still more than you expect.

Photos are welcome, but tripods slow traffic and earn frowns. Keep your bag slim and your shoes quiet.

If you want music and engines in one visit, first Saturday is the high percentage play.

Final tip: build flex into your day. Demos cluster, conversations bloom, and you will not want to clock out early.

The best visits stretch just a bit past whatever you planned, like the last note of the Wurlitzer leaning into an echo you can feel under your ribs on the walk back to the car.