In May 1933, thousands of people were deported to a small swampy island in Siberia with almost no food, shelter, or tools. What unfolded on Nazino Island became one of the starkest tragedies of Stalin’s rule, later known as Cannibal Island.

Drawing on archival records and firsthand testimony, these verified facts explain what happened and why it mattered. Read on to understand the context, the human toll, and how the truth finally emerged.

In May 1933, during the height of forced collectivization and internal deportations, Soviet authorities sent thousands to Nazino Island. The timing intersected with famine, mass arrests, and sweeping urban passport checks that categorized many people as socially harmful.

This convergence made the operation unusually chaotic and brutal from the start.

The month matters because spring thaw left the Ob River swollen and the island waterlogged. Supply lines were fragile, and officials prioritized speed over preparation.

As a result, deportees arrived before any workable plan for shelter or distribution existed, magnifying the crisis.

Primary sources include Soviet internal correspondence, transport manifests, and later inquiries by party officials. Historians cross reference these with survivor testimonies to reconstruct the timeline.

The documentation aligns on core points: the deportations occurred in mid May, the island was unprepared, and conditions deteriorated within hours.

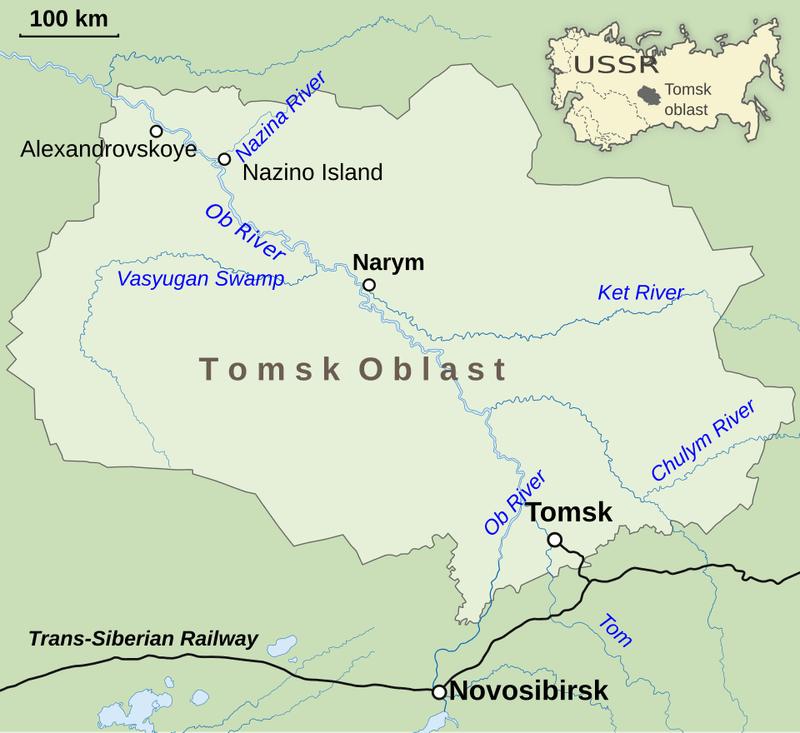

Archival figures indicate roughly 6,000 to 6,700 people were transported to Nazino Island. Trains and barges moved deportees from cities to staging points, then along the Ob River.

Headcounts varied by embarkation stop, but all credible estimates place the number well above six thousand.

Capacity planning did not match the scale of arrivals. Administrators lacked accurate rosters and issued flour rations without a distribution system.

Crowding on barges led to exhaustion and illness before anyone reached the island’s mud and brush.

Historians use overlapping rosters and NKVD summaries to triangulate the total. Though some documents conflict on exact tallies, the range is consistent across independent research.

The numbers matter because logistics for shelter and food should have scaled accordingly, yet no such preparation existed.

Although labeled socially harmful elements, many deportees were ordinary city residents swept up in passport sweeps. People lacking internal documents, including workers between jobs, migrants, and the homeless, were detained quickly.

The label criminal did not reflect due process or proven offenses.

Testimonies describe market vendors, students, and laborers suddenly arrested during checks. Some detainees expected brief verification but instead faced immediate transport.

Confusion persisted because detainees received little explanation or legal recourse before relocation.

Researchers cite police directives and urban passport regulations from early 1933 to explain how non criminals were ensnared. The system emphasized quotas and rapid throughput, not verification.

As a result, the island included a cross section of urban life, many unprepared for survival conditions.

The Nazino transports aligned with a broader plan to settle up to two million people in remote Siberian areas. Policymakers aimed to populate frontier zones, cultivate land, and secure resources quickly.

Colonization combined punishment, social engineering, and economic goals under centralized control.

Planning papers envisioned new settlements with agricultural teams and basic infrastructure. In practice, rapid execution outpaced logistics.

Officials diverted detainees to sites like Nazino without shelters, tools, or trained supervisors.

Scholars compare Nazino with other special settlements that housed deported peasants and urban detainees. The overarching system mixed penal elements with improvised colonization.

Nazino became an extreme failure case, illustrating what happened when quotas and ideology overrode capacity.

Nazino Island sat low in the Ob River, swampy, windswept, and exposed. There were no permanent structures, no latrines, and no storage.

Landing zones turned to deep mud as barges unloaded people and sacks of flour.

With no tools or timber supplies ready, deportees could not build reliable shelters before nightfall. Fires sputtered on wet ground, and smoke offered scant relief from cold.

Improvised lean tos collapsed under weather and crowding.

Reports from investigators noted the complete absence of preparation. Even basic tasks like organizing ration lines proved unworkable in marshy terrain.

The island’s geography magnified every shortcoming, turning logistical gaps into immediate health and safety crises.

On arrival, deportees received small amounts of flour rather than bread or cooked rations. Without ovens, pots, or fuel, many mixed flour with river water to make paste.

Some tried to cook lumps on sticks over smoky fires, often losing food to mud and ash.

Distribution broke down under pressure. Guards struggled to control lines, and sacks were sometimes torn open in panic.

Starvation set in as weak and ill people could not reach rations or keep them.

Archival accounts describe flour as the primary provision for days. There were no steady deliveries of meat, vegetables, or salt.

The nutritional gap worsened exposure and disease, linking food scarcity to the rapid death toll.

Overcrowding, exposure, and contaminated water accelerated disease on the island. People drank directly from the river or puddles near latrines, spreading infections quickly.

Malnutrition weakened immune systems, turning minor ailments into lethal threats.

Witnesses noted dysentery symptoms, fevers, and swelling from scurvy and protein deficiency. With no medical posts or trained staff, the sick lay on wet ground.

Bodies accumulated faster than they could be removed or buried.

Investigators later linked the outbreak to sanitation failures and inadequate supplies. Epidemiological patterns fit well known camp conditions documented in other settlements.

The speed of transmission reflected extreme density and the absence of clean water, shelter, and rest.

The NKVD deployed armed guards to encircle the island and patrol the riverbanks. Orders discouraged escape attempts, and gunfire was reported when people tried to swim away.

The river’s cold currents and distance to settlements compounded the barriers.

Some detainees hid in brush or fashioned rafts, but most efforts failed. Guards intercepted groups and returned or shot them.

Survivors recalled gunshots at night and bodies along the shoreline.

Official records acknowledge shootings and recaptures. Security protocols prioritized containment over safety, reflecting a penal approach rather than resettlement support.

The combination of force and natural obstacles trapped thousands in untenable conditions.

Scarcity and fear led to widespread violence within days. Small gangs formed to seize rations, clothing, and space near fires.

Weaker people, including the ill and elderly, were frequent targets as order collapsed.

Witness accounts describe beatings over flour and theft of boots or coats at night. Without authority structures or fair distribution, retaliation spiraled.

Guards intervened sporadically, often too late to prevent injury or death.

Historians compare these patterns to breakdowns in other crisis camps where resources were limited. Social bonds frayed under hunger and exposure.

The violence was not isolated incidents but a systemic outcome of unmanaged deprivation.

Survivor testimonies and official reports documented cases of cannibalism on the island. Researchers approach this evidence cautiously, corroborating multiple sources to avoid exaggeration.

The accounts consistently connect cannibalism to extreme starvation and the collapse of social controls.

Investigators recorded arrests related to mutilation of bodies and attacks on the living. Eyewitnesses described guards discovering remains and detaining suspects.

The island’s nickname, Cannibal Island, stems from these records rather than rumor alone.

Responsible reporting avoids sensational detail while acknowledging the verified facts. The evidence underscores how quickly desperate conditions erased basic norms.

It remains one of the most disturbing aspects of the Nazino tragedy.

Deaths began within the first 24 to 48 hours, driven by exposure, exhaustion, and shock. People arrived already weakened by transport and lack of sleep.

Cold wind, wet clothing, and no shelter accelerated hypothermia.

Witness statements and internal tallies mention bodies found each morning near fire pits and shoreline. Many lacked shoes or coats, having lost them during fights or barter.

Some died while waiting for rations that never reached them.

Researchers estimate early fatalities in the hundreds, consistent with later mortality totals. The pace of death shows how preparation failures had immediate consequences.

Once health collapsed, few recovered without rest, warmth, or medical care.

By late spring, thousands were dead or dying. Historians estimate at least 4,000 people perished within weeks, either on the island or shortly after removal.

This includes deaths from disease, starvation, exposure, shootings, and transport aftermath.

Records from camp administrators and inquiries provide overlapping figures. While exact counts vary, the scale is indisputable.

Survivors transferred to other sites often succumbed soon after, extending the toll beyond Nazino itself.

Demographers examine age, health, and ration data to model mortality curves. The catastrophic losses align with conditions seen in other famine and camp crises.

The outcome reflects systemic failure rather than isolated misfortune.

Vasily Velichko, a Soviet party official, investigated reports from the region and compiled a detailed account. He interviewed witnesses, guards, and survivors, documenting logistics, rations, and abuses.

His report became the foundational narrative for understanding Nazino.

Velichko’s work combined on site observations with administrative records. He described the island’s terrain, supply failures, and security practices.

The clarity of his findings contrasted with the vagueness of earlier communications.

Historians rely on his report because it triangulates various sources under official authority. While subsequent research added context, his documentation preserved facts that might have been lost.

Without Velichko, much of the event’s detail would remain obscured.

After submission, Velichko’s report was suppressed and classified. Circulation remained limited to senior officials, and public discussion was impossible.

The broader public learned little or nothing for decades.

Only in the late Soviet period did archival access expand. Glasnost reforms and historical initiatives brought the Nazino materials to researchers.

Journalists and scholars then synthesized the documents into accessible accounts.

The delay shaped memory and accountability. By the time sources opened, many witnesses had died.

Even so, the release allowed independent verification and placed Nazino within a documented pattern of repression and neglect.

Nazino was part of a wider system of forced deportations and special settlements. Across the Soviet Union, millions endured relocation, harsh labor, and inadequate supplies.

Some sites functioned for years, with fluctuating mortality depending on leadership and logistics.

Researchers compare Nazino to other failures where sudden transfers overwhelmed capacity. While not every settlement collapsed so quickly, systemic risks were constant.

Quotas, secrecy, and resource scarcity undercut humane administration.

Placing Nazino in this context helps explain both its scale and its speed. It was extreme, but not unimaginable within prevailing policies.

The tragedy illustrates how ambitious targets without planning translated into preventable death.

The Nazino narrative rests on multiple credible sources. Key materials include Velichko’s report, NKVD records, transport documents, and regional archives.

Historians also draw on survivor testimonies collected after declassification and during local investigations.

Modern scholarship synthesizes these primary sources with demographic analysis. Works by Russian and international researchers cross check numbers, dates, and events.

The overlap across independent studies strengthens confidence in core facts.

When reading about Nazino, look for citations to archives and published academic monographs. Reliable accounts avoid sensationalism and specify uncertainties.

This approach aligns with best practices for reconstructing events in closed, repressive systems.