The North Magnetic Pole is not standing still, and the latest shift is already pressuring defense, aviation, and tech systems to adapt fast. If you rely on maps, autopilots, drones, or satellites, the numbers under the hood just changed.

This is not a distant scientific curiosity but a live operational issue with real navigation and safety stakes. Here is what moved, why it matters, and how you stay ahead of it.

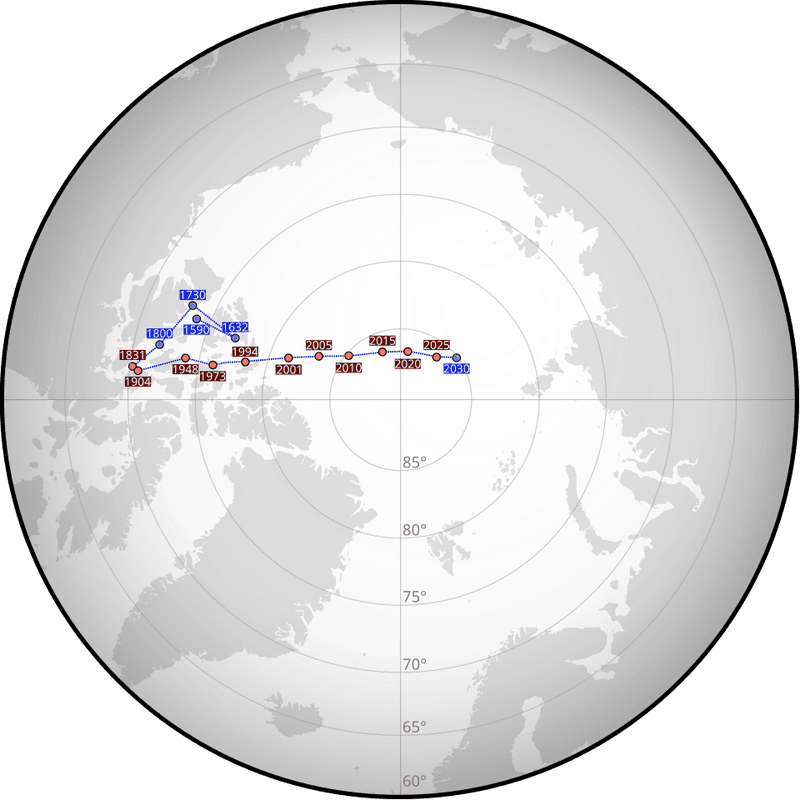

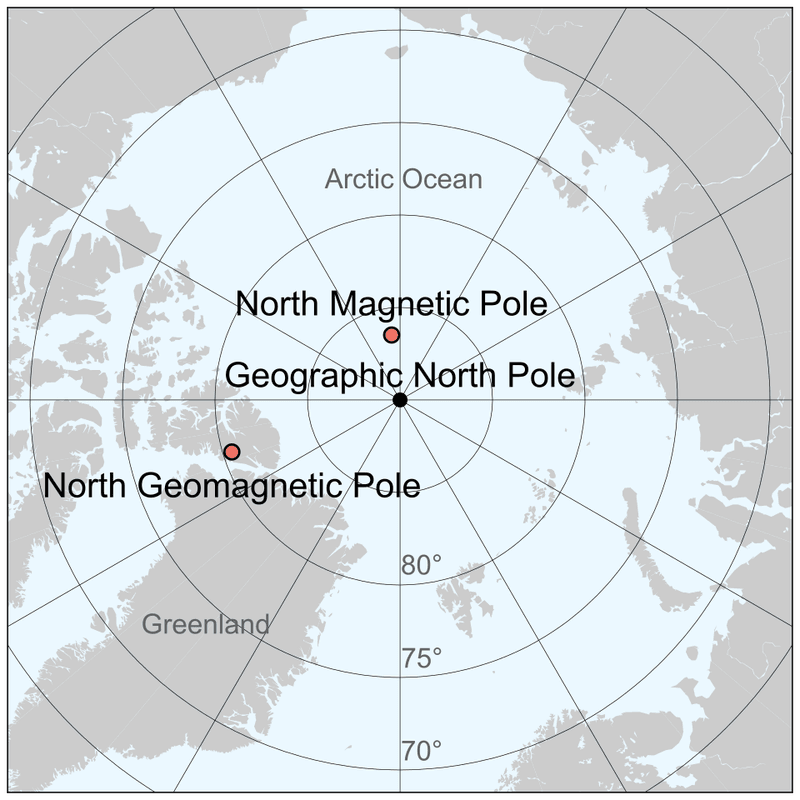

The pole’s crossing into the Russian hemisphere in 2025 is more than a cartographic milestone. At 86.38°N, 164.06°E, magnetic north now sits closer to Russian air and sea corridors, altering reference frames used by aircraft, ships, and sensors.

If you operate in polar routes or high latitudes, heading solutions and course corrections will feel slightly different, with corrections accumulating over distance. This shift demands recalibration across platforms that assume a historical alignment with Canadian Arctic reference points.

Autopilots, inertial navigation systems, and even handheld compasses depend on the right declination model to stay honest. When those angles drift, small errors compound into meaningful deviations, especially during instrument procedures and remote operations.

Defense planners are adapting flight planning, missile guidance margins, and geo-fencing tied to magnetic azimuths. Civil operators should mirror that urgency, verifying that charts, mission planners, and mobile mapping engines ingest the latest model data.

The physics did not change overnight, but the coordinates did, and your software must speak the new language. The World Magnetic Model underpins everything from your phone’s compass to a fighter jet’s heading reference.

Built by NCEI and BGS, WMM2025 and its high resolution sibling WMMHR2025 update the field’s secular change so instruments point where they should. If your platform trusts magnetic azimuths, it quietly trusts WMM.

Defense, NATO, and allied agencies treat these models as baseline truth for navigation, mission planning, and geospatial alignment. Civil aviation databases, maritime ECDIS, and drone autopilots ingest their coefficients to correct headings and bearings.

Without routine updates, even well tuned sensors give you beautifully consistent but wrong answers. Think of WMM as a living calibration file for the planet.

When the magnetic field evolves, the model translates physics into numbers your systems can use. When you apply those numbers regularly, maps line up, tracks align, and your situational awareness stays sharp.

Since the 1830s, the pole has walked more than 2,200 kilometers across the Arctic, a marathon powered by Earth’s churning core. Between 1990 and 2020, speeds hit roughly 60 kilometers per year.

As of 2025, the pace eased to about 35 kilometers per year, still brisk by historical standards. For operators, velocity matters as much as position.

Faster motion narrows the buffer before charts and software drift out of spec. WMM2025 captures these updates using spherical harmonics up to degree 12, modeling toroidal and poloidal components that shape regional differences you will notice in headings.

The takeaway is simple. Forecast skill over five to ten years is solid, but complacency ages fast.

If your workflows assume slow change, build in checks that flag stale coefficients before they quietly erode precision across fleets. WMMHR2025 pushes spatial detail dramatically, taking effective resolution from thousands of kilometers down to hundreds.

That leap matters for satellites skimming low Earth orbit, drones threading valleys, and guided systems that demand sub kilometer directional truth. When terrain, latitude, and field gradients interact, coarse models blur reality.

By extending harmonics to degree 36, the high resolution variant teases out smaller scale features your sensors will actually see. You get fewer residuals, cleaner heading solutions, and less post processing to iron out bias.

It is the difference between a rough sketch and a tight blueprint. If you operate fleets, align your updates with WMMHR2025 where feasible.

You will spend less time chasing anomalies, and more time trusting what the autopilot reports. In high drift regions, that trust translates directly to safety margins and fuel planning.

Shadow zones near the poles weaken the horizontal field below 2,000 nT, leaving compasses wobbly and easily misled. If you fly polar corridors, trek on ice, or pilot vessels in extreme latitudes, heading references degrade fast.

WMM2025 refines those boundaries so planners can reroute or layer sensors intelligently. In these regions, you should avoid relying on magnetics alone.

Fused solutions that blend GNSS, inertial, celestial, and vision based navigation keep guidance stable when needles lose authority. Redundancy is your friend where even small gusts of field variability nudge bearings.

The practical move is to brief crews and mission software with updated risk maps. Put shadow zones into your decision aids, precompute alternatives, and require cross checks during long legs.

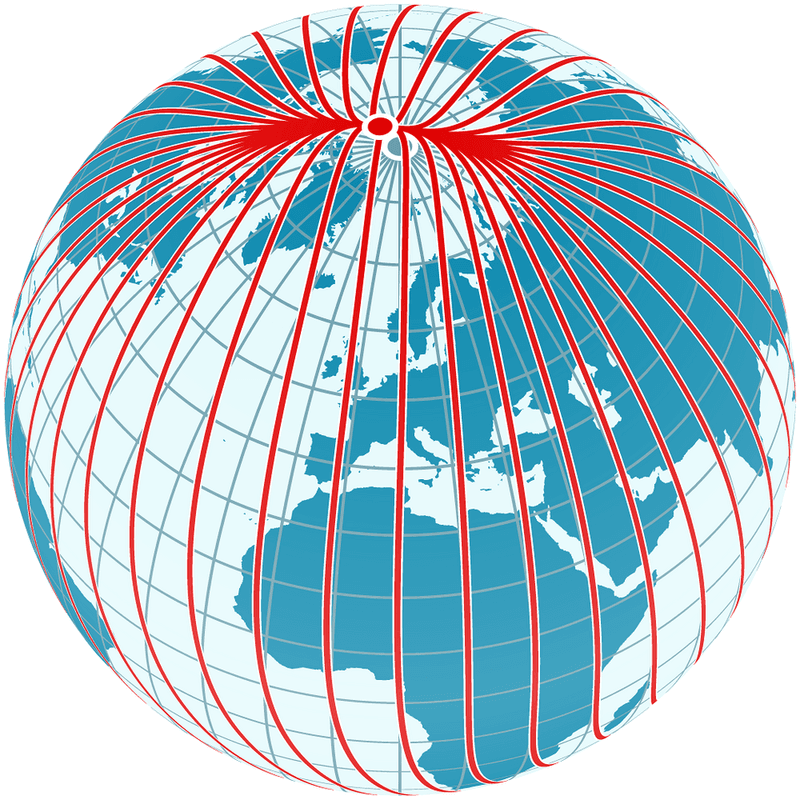

The physics will not accommodate wishful thinking, but smart planning carries you through. Magnetic declination is simply the angle between true north and magnetic north, but the consequences are not simple.

In parts of Alaska, that offset has shifted more than 10 degrees over two decades. If your procedures assume yesterday’s angle, headings and bearings can drift into unsafe territory.

WMM updates every five years with NGA and DGC coordination, and 2019’s mid cycle fix proved how quickly accelerations can force recalibration. Aviation charts, maritime ENC updates, and autonomous stacks must eat those new numbers promptly.

Your autopilot and your map database need to agree before you launch. To manage risk, schedule periodic compass swings, verify EFB chart currency, and confirm that mission planners export the right declination to onboard systems.

Cross check with test tracks or approach procedures you trust. Small angles add up, so catch them early.

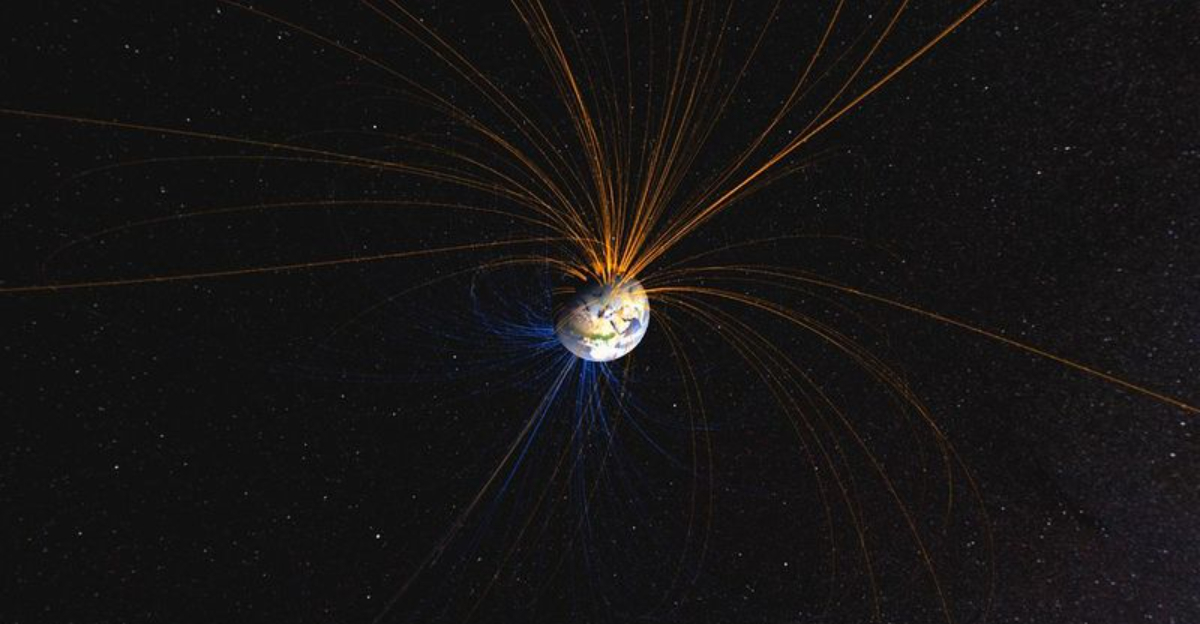

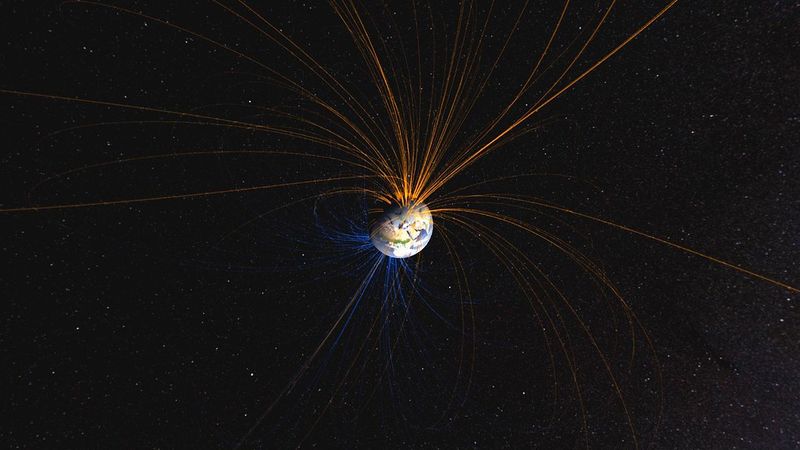

Beneath your feet, 2,900 kilometers down, liquid iron convects and generates our magnetic shield. Those flows twist, shear, and spawn features like the tangent cylinder, flux lobes, and the South Atlantic Anomaly.

The pole’s migration is a surface symptom of that deep engine. Satellites such as Ørsted, CHAMP, and Swarm have mapped the field exquisitely, but the mantle’s role still clouds the picture.

That is why long horizon forecasts remain speculative, even as five to ten year predictions hold water. You can trust near term guidance while planning for surprises beyond it.

For operators, the lesson is humility blended with discipline. Update models on schedule, keep an eye on anomaly regions, and maintain sensor diversity.

The core will do what it does, and your best defense is agile calibration. Headlines love the word reversal, but WMM2025 does not point to a flip any time soon.

Full reversals happen on scales of two to three hundred thousand years, with the last one roughly 780,000 years ago. Excursions like the Laschamps event are scientifically rich but not an operational red alert today.

What you are seeing now is drift and regional reshaping, not a wholesale swap of poles. That matters because planning horizons for defense and aviation rarely stretch beyond decades.

Sensible, steady recalibration will beat apocalyptic speculation every time. So keep the focus tight.

Align with current models, watch anomaly updates, and communicate clearly with crews and customers. Stability comes from process, not bravado.

WMM2025 is not optional if you expect headings to behave. Inertial systems, magnetometers, and calibration software depend on fresh coefficients to keep drift within tolerances.

Regulators already require periodic updates for aviation and maritime operations, and audits look for proof. The pain point is rollout, especially across legacy fleets that hide magnetic assumptions deep in firmware.

Some platforms need dockside or hangar time for a full compass swing. Others require patched mission planners so exported routes carry the right declination and grid references.

Your playbook should include version control for model files, hot spares for sensors, and a cutover checklist that crews can execute. Document it, simulate it, and verify it with known tracks.

The cost of delay shows up as deviations, fuel burn, and sometimes incident reports. Open questions are stacking up.

If pole motion re accelerates, the five year cadence might be too slow for high stakes corridors. Emerging Southern Hemisphere anomalies could complicate routing and degrade instruments where operators least expect it.

Autonomous systems will feel the squeeze first, because they digest angles continuously and act without human intuition. As regions approach the current disappearance threshold, planners must blend IMU, GNSS, vision, and terrain correlation to avoid magnetic dependence.

Testing those stacks under polar like conditions is no longer optional. The path forward mixes research, standards, and ops discipline.

Push for telemetry sharing, champion faster model distribution, and rehearse degraded mode procedures. The systems that win will be the ones that fail gracefully.

The pole’s march toward Russia is a reminder that navigation lives in a moving world. With WMM2025 and WMMHR2025, you can keep charts honest, sensors synchronized, and crews confident.

The work is procedural, not glamorous, but it pays off every day you launch. Build updates into your maintenance rhythm, validate headings against trusted references, and treat high latitude ops with deliberate redundancy.

When field gradients bite, layered navigation will save the mission. Precision is a habit, not a switch.

Adopt the high resolution model where it helps, brief shadow zones, and keep an eye on anomaly bulletins. You are not chasing perfection, just staying inside safe margins as Earth’s magnetic story evolves.

Keep calibrating, keep flying straight, and the globe stays navigable.