An 80-mile crack ripped across Lake Erie’s frozen surface on February 8, 2026, stunning residents who said it sounded and felt like an earthquake. The fracture was so vast it showed up clearly on weather satellites, unfolding over hours as the ice shifted and split.

Officials say the lake was almost entirely frozen when it happened, which can set the stage for dramatic breaks. Here is what happened, why it happened, and why it matters for safety and science.

The crack stretched an estimated 80 miles

The fracture that tore across Lake Erie on February 8 was not a hairline fissure near shore. It stretched an estimated 80 miles, a distance large enough to cut across multiple basins and challenge how we picture a frozen lake’s stability.

From the ground, it looked like a dark seam, sometimes several feet wide, winding beyond view.

On the ice, long straight sections alternated with gentle curves, telling a story of tension and release. The magnitude matters because such length means stresses were transmitted far from the origin, accumulating until a failure ran like a zipper.

You could stand on the shore and trace the line with binoculars for minutes without reaching its end.

Local officials said the crack likely formed where wind-driven forces and underlying currents met the strongest gradients in ice thickness. That created a failure path the stress could follow efficiently.

The size alone turns a winter spectacle into a community hazard, splitting familiar routes and isolating areas people assume are safe.

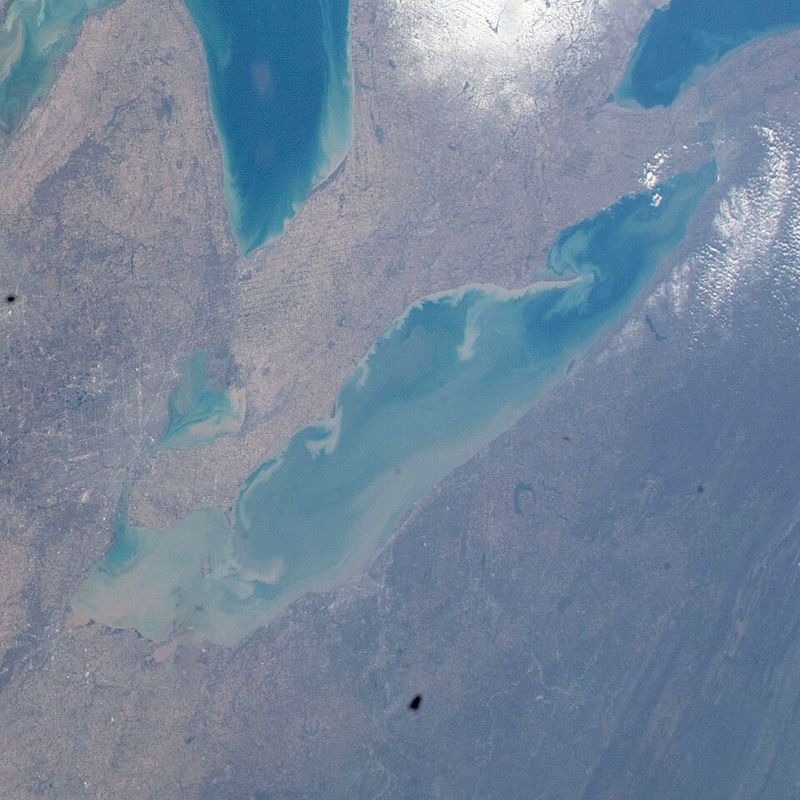

It was visible from space

The crack was so large and stark that it registered clearly on satellite imagery. That is unusual for ice fractures on inland lakes, which often blend with cloud shadows or thin ice streaks.

In this case, a dark, high-contrast line split the bright expanse of Lake Erie, signaling a structural break rather than a surface blemish.

From 22,000 miles up, geostationary sensors do not typically resolve fine features over the Great Lakes. Yet the fracture’s width and thermal contrast stood out across multiple frames.

The visibility underscores how abrupt and energetic the failure was, altering the surface enough for broad scale detection.

Seeing it from space also meant forecasters could quickly verify what residents were hearing and feeling onshore. Emergency managers shared annotated loops to warn anglers and snowmobilers to avoid unstable areas.

Space-based confirmation turned anecdote into documented event, speeding decisions and placing the crack into a regional context.

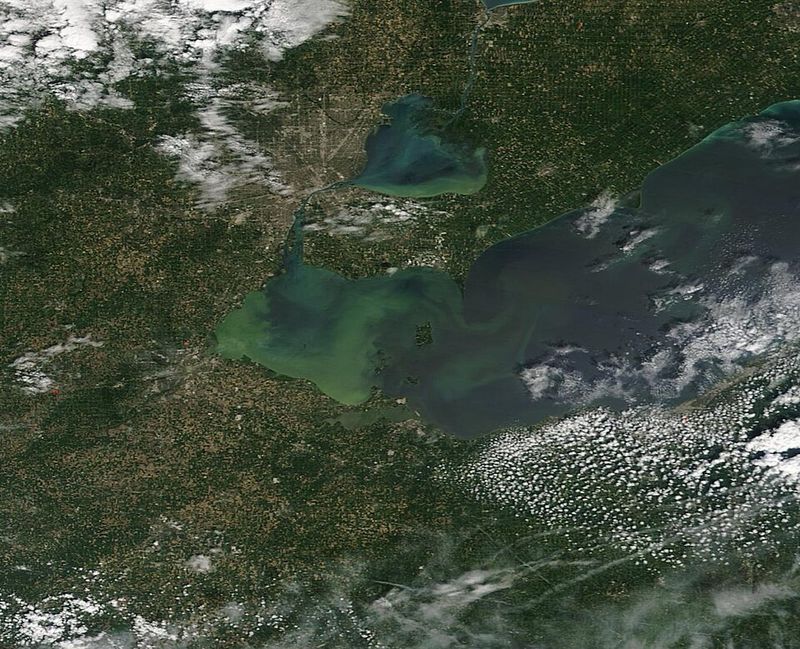

GOES-East captured it forming in real time

GOES-East, the geostationary weather satellite serving the eastern United States, captured the fracture forming in real time. In rapid loops, a thin line appeared, then widened and lengthened as daylight progressed.

The animation looked almost surgical, a cut slicing through continuous ice and branching slightly at stress points.

Forecasters watched the evolution frame by frame, noting when the line first emerged and how quickly it propagated. The speed suggested a cascading failure where one section’s release redistributed stress to the next.

That is a hallmark of brittle systems, where gradual pressure suddenly culminates in an all-at-once break.

Real-time imagery provided more than spectacle. It offered timing, orientation, and rate-of-change information, allowing meteorologists to infer wind alignment and current contributions.

For the public, seeing the moment of failure helped explain why the lake sounded alive with booms and cracks, and why conditions flipped from seemingly solid to hazardous within hours.

The lake was about 95% frozen

NOAA ice analyses showed Lake Erie was roughly 95 percent covered by ice when the crack formed. That sounds reassuring, but near-total coverage can be deceptive.

Instead of lots of independent floes, the lake behaves like a single, connected plate able to carry and concentrate stress across large distances.

Uniform ice cover reduces the options for motion to diffuse gently. When wind and current forces ramp up, the energy must be accommodated somewhere along the sheet.

The result can be a sudden, clean fracture when the weakest pathway finally yields.

High coverage also allows pressure to build silently. People standing on thick ice may feel confident, reading the surface as stable.

In reality, buried weak layers, variable thickness, and temperature gradients set the stage for abrupt failure. When it goes, it goes fast, explaining why observers reported shakes and booms rather than gradual creaks.

Near-total ice cover can behave like one giant sheet

When a lake nearly freezes over, it often functions mechanically like a single sheet. Stresses introduced at one location can travel surprisingly far because the ice is bonded and stiff.

That creates conditions where a fracture can initiate remotely from where the highest winds or currents are occurring.

Think of it as a pane of tempered glass stretched over water. It can flex a little, then suddenly snap along a line that best relieves the accumulated strain.

The snap does not necessarily happen where you push, but where the structure is primed to fail.

This behavior explains why the Lake Erie crack formed as a relatively straight, continuous feature instead of a patchwork of random breaks. Once a path with the least resistance existed, the fracture raced along it, linking weak spots that might otherwise have stayed quiet.

The bigger the connected sheet, the bigger and cleaner the break can be.

Wind and currents can turn solid ice into a moving machine

Even when ice looks locked in place, wind and currents keep pushing and pulling. Friction with the air moves the surface, while subsurface flows tug from below, creating shear.

Over hours, that constant nudge builds pressure along hidden seams until the structure gives way.

On February 8, wind aligned across long fetches on Lake Erie, enhancing momentum. Currents associated with basin circulation likely added crosswise stress.

The combination converts a tranquil scene into a kinetic system, with forces that rival what you feel on an old wooden ship groaning under strain.

Once the ice fails, the motion does not stop. The new edges can slide, rotate, and pile up, expanding the gap and creating chaotic ridges.

That is why a narrow fissure at noon can become an open lead by afternoon, turning a comfortable walk into a risky crossing with icy water churning just beneath the surface.

Forecasters warned about shifting and ridging

The National Weather Service office in Cleveland warned that the ice was actively shifting, ridging, and rafting before the major fracture occurred. Those terms are red flags for unstable conditions.

They describe mechanical changes that happen when ice plates collide, overlap, and buckle under stress.

Forecasters issued marine and public statements urging caution, especially for anglers and anyone traveling on frozen bays. The alerts mentioned rapidly changing leads and pressure ridges that could block traditional routes.

That messaging helped some residents decide to stay off the ice entirely that weekend.

Warnings like these rely on satellite loops, surface observations, and reports from local agencies. When they reference ridging and rafting, it means the system is already in motion, not theoretically stressed.

In other words, the dice are rolling. With the February 8 event, the warnings proved prescient, arriving hours before the long crack fully revealed itself to the entire lakeshore.

Ridging and rafting are violent ice processes

Ridging happens when ice plates push together and stack like broken masonry. Blocks tilt, climb, and lock into jagged walls that can rise several feet above the surface.

Rafting is similar but flatter, as one sheet slides atop another, forming a step rather than a pile.

Both processes are violent at the scale of human movement. You may hear grinding, cracking, and hollow booms as the ice rearranges itself under pressure.

These shifts can propagate quickly, reopening old cracks and carving new ones that radiate outward.

During the Lake Erie event, ridging and rafting likely intensified local stresses until a long fracture offered a cleaner release. Once the failure line formed, nearby plates could reorganize more freely, expanding gaps and sprouting new ridges.

For anyone on the ice, these features are both obstacles and warnings, broadcasting that what looked solid moments ago is now an active construction zone under your feet.

Locals reported booming sounds and shaking

People living along Lake Erie’s shore described loud cracks and deep, percussive booms that rattled windows. Some felt vibrations underfoot, likening the moment to a small earthquake.

Pets reportedly reacted first, followed by neighbors stepping outside to scan the ice for movement.

The sounds travel well across flat, frozen expanses. When a fracture releases tension, it can send acoustic waves that bounce between the ice and the air.

That resonance amplifies the experience, turning a distant break into a neighborhood event.

Descriptions were remarkably consistent across communities, suggesting a widespread structural change rather than isolated settling. While the shaking was not a tectonic quake, the comparison makes sense.

It is how sudden mechanical energy feels and sounds when the ground itself participates, even if that ground is a temporary sheet of winter ice.

The event may qualify as an ice quake

Scientists use the term cryoseism, or ice quake, to describe sudden releases of energy from rapidly shifting or fracturing ice. These events can produce seismic signals detectable on nearby instruments, along with audible booms.

The Lake Erie fracture checks many boxes, from abrupt onset to widespread acoustic reports.

Unlike tectonic earthquakes, cryoseisms are driven by thermal contraction, pressure from wind and currents, and structural failure of ice slabs. They do not signify faults deep underground.

Instead, they mirror brittle fracture mechanics at the surface, where temperature gradients and motion collide.

Whether this event will be logged as an ice quake depends on seismometer records and timing alignment with the satellite-observed break. If instruments show a spike corresponding to the fracture, the classification strengthens.

Either way, the phenomenon helps explain why residents described an earthquake-like feeling, even as the cause rested atop the lake rather than below it.

It created a major safety hazard for anyone on the ice

A fracture this long can open rapidly into a lead, a ribbon of open water that isolates people in minutes. Anglers, snowmobilers, and hikers are especially at risk because routes they trusted an hour earlier may vanish.

If you end up on the far side, the floe can drift away, pushed by wind before help arrives.

Rescues on moving ice are complex and dangerous. Responders need specialized gear, boats, and sometimes air support to reach stranded groups.

Cold water shock adds urgency, turning slips near the edge into life-threatening emergencies.

Officials advise carrying ice picks, flotation, and a charged phone, and never traveling alone. Watch for pressure ridges, listen for booms, and backtrack at the first sign of widening gaps.

On days like February 8, the best safety choice is often simple: stay off the lake until the ice stops reorganizing and conditions stabilize.

Scientists say Lake Erie’s ice is becoming harder to predict

Lake Erie is shallow, warms and cools quickly, and reacts strongly to weather swings. Some winters it nearly freezes end to end, while others remain mostly open.

That variability can produce more whiplash events where ice forms, consolidates, then breaks apart under shifting winds.

Researchers say increased temperature volatility and fast-moving storm tracks complicate forecasts. Models can capture broad trends, but local thickness, snow cover, and currents still drive surprises.

The February 8 fracture fits that pattern, a big response emerging from subtle imbalances.

For communities and anglers, the takeaway is humility. Treat each day’s ice like a new system, not a continuation of yesterday’s conditions.

Check forecasts, look at recent satellite loops, and remember that near-total cover can raise, not lower, the risk of dramatic failures. Predictability is toughest when the lake hovers between seasons, and that shoulder state is showing up more often.