Walk down a city street that’s slowly sinking and you might not notice the danger at first. There’s no sudden collapse, just small, easy-to-ignore changes: a door that starts sticking, a crack that wasn’t there last year, a sidewalk that tilts a little more after every rainy season.

Most people blame age or poor construction. But sometimes those “quirks” are early signs of land subsidence – the ground itself quietly dropping beneath the city.

What surprised scientists wasn’t just how common this problem is, but what can help slow it down. In some places, the most effective fix has been counterintuitive: carefully pumping water back underground to restore pressure and support the land from below.

The Ground Under Cities Isn’t Solid – It’s More Like a Sponge

The ground beneath many big cities isn’t solid rock. It’s often made of layered sediment – sand, silt, and clay packed tightly together.

Between those tiny grains are microscopic pores, and those pores are filled with fluids like groundwater, oil, or gas. That fluid pressure matters because it helps support the weight of everything above, from roads and buildings to entire neighborhoods.

As long as the pores stay full and pressurized, the ground can hold its shape. But when people pump fluids out faster than nature can replace them, the pressure drops.

The grains shift closer together, the layers compress, and the surface begins to sink. That’s why engineers now treat subsurface pressure like invisible support: manage it carefully, and cities stay steadier.

Why Pumping Fluids Makes Cities Sink

Here is the chain reaction. Pump water or hydrocarbons too fast, and pore pressure drops.

With less internal support, sediment grains shoulder more weight. The sponge compresses, and the ground surface begins to sink.

This is not guesswork. It is measured physics repeated across continents.

Groundwater, oil, gas: the details differ, but the mechanics rhyme. Remove pressure quickly, compaction accelerates.

Keep doing it, and structural damage appears topside. Slower extraction can help, but sometimes the damage has already begun.

Once grains rearrange tightly, much of that volume loss is permanent. Even if fluids return, pores may not rebound.

That is why prevention and pressure management matter early. Waiting turns a manageable issue into an expensive, long-running problem.

The First Warning Signs Are Almost Always ‘Boring’

Subsidence rarely begins with a headline-grabbing collapse. Instead, it whispers through daily nuisances.

Doors that suddenly stick. Windows that do not shut cleanly.

Hairline cracks snaking across stucco. Sidewalks buckling just enough to trip a hurried commuter.

Storm drains that cannot quite keep up anymore.

Individually, each flaw seems mundane, blamed on age or shoddy repairs. Together, they tell a larger story: ground shifting in slow motion beneath neighborhoods.

Utilities notice it too, through more frequent pipe breaks and awkward joint angles.

It can take years for a city to connect the dots. By then, patterns span blocks and districts.

What felt like maintenance noise becomes evidence of the surface settling. The lesson is simple: boring patterns are early warnings.

Mexico City: The Mega-City That’s Sinking Faster Than Many Coastlines Rise

Mexico City sits atop ancient lakebed sediments that compact under stress. Over the last century, parts have dropped more than 7.5 meters.

That is the height of a two-story house erased from elevation. Some neighborhoods still see 40 to 50 centimeters of loss each year driven by deep groundwater pumping.

What makes it worse is irreversibility. Once clay layers compress beyond a threshold, they do not puff back up.

Even if water tables recover, the fabric of the soil has rearranged. The city has tried to curb extraction and diversify supplies, but legacy compaction remains.

So planning now treats lost elevation as permanent. Adaptation focuses on flood risk, drainage redesign, and protecting critical infrastructure as the ground continues its slow descent.

Why Subsidence Is a Coastal City’s Worst Nightmare

Coastal cities already battle rising seas. Add land subsidence, and the effective elevation drops from both directions.

Even small amounts of settling can push storm surges farther inland, undermine seawalls, and flood tunnels that once stayed dry. Drainage systems lose head, so water lingers longer.

Salty groundwater creeps upward through stressed aquifers, threatening foundations and utilities. Pumps work harder, burn energy, and still fall behind during heavy rain.

What looked like a one-in-100-year flood shows up more often.

Unlike sea-level rise, subsidence can accelerate quickly when extraction ramps up. That speed makes planning tricky.

A few centimeters here can redraw a risk map. For low-lying districts, that is the difference between nuisance pooling and knee-deep street floods.

The Obvious Question: What If We Put the Pressure Back?

Once you know pressure loss drives sinking, a simple idea follows: restore it. Instead of only pulling fluids out, inject water carefully back into the drained layers.

Could that slow subsidence, halt it, or even nudge land upward a bit? In some cities, yes.

This is not flooding the subsurface blindly. It is targeted, measured, and modeled.

Engineers watch pore pressures and ground motion in near real time, adjusting injection rates. The goal is stability, not overcorrection.

Early programs showed that introducing water can shrink the footprint of severe sinking. Uplift sometimes appears, but the safer promise is braking the descent.

That breathing room buys time for redesigning drainage, reinforcing levees, and protecting what matters most.

Long Beach, California: The Place That Learned the Hard Way

Long Beach rode a petroleum boom above the Wilmington Oil Field and paid dearly. Mid-20th century extraction triggered dramatic subsidence.

Harbor zones slumped by as much as nine meters, nearly 30 feet, in a dense industrial landscape. Docks, pipelines, roads, and buildings distorted.

The threat was existential for a major port. Damage spread, and the city faced potentially losing parts of its coastline.

Emergency engineering shifted from production to preservation.

The lesson was stark: reservoirs do not just give oil, they provide pressure that props up the land. Remove it without a plan, and the ground follows the fluids.

Long Beach became a global case study, spurring one of the first large-scale, coordinated injection responses.

The ‘Upside-Down’ Solution: Massive Water Injection

Engineers countered Long Beach subsidence by injecting water back into the Wilmington field. Treated seawater and produced water flowed through hundreds of wells, restoring pore pressure.

As volumes increased, the area of severe sinking shrank from roughly 58 square kilometers to about 8.

In some spots, the ground rebounded around 30 centimeters. Overall, subsidence slowed to a crawl.

No miracle, just physics applied with discipline: pumps, gauges, and iterative control.

The effort became a template for managing extraction with pressure maintenance. It proved invisible infrastructure could protect visible infrastructure.

Ports, refineries, and neighborhoods stayed workable while the subsurface regained balance. The big takeaway: you can stabilize the earth without touching the skyline.

What Water Injection Really Is: An Invisible Scaffold

Think of injection as erecting a scaffold you will never see. Instead of steel, it is pressure distributed through pore spaces.

That pressure supports part of the load that buildings, roads, and seawalls transmit downward. When tuned carefully, it keeps sediments from collapsing further.

The beauty is subtlety. Streets look unchanged, but sensors record stability where there was steady descent.

No ribbon-cuttings or skyline transformations, just quiet protection from below.

Get it wrong, and risks appear. Push pressures too high or into the wrong layers, and faults may respond.

That is why modern programs lean on data and patience, treating the subsurface like a living system rather than a static tank.

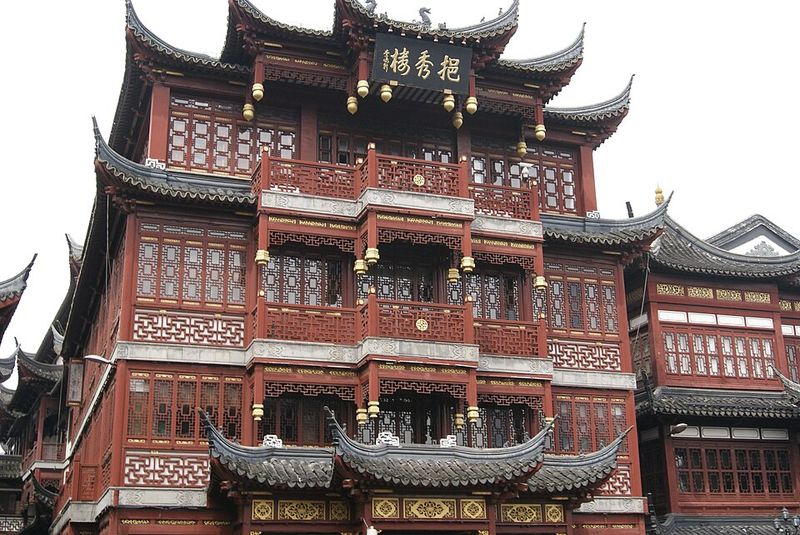

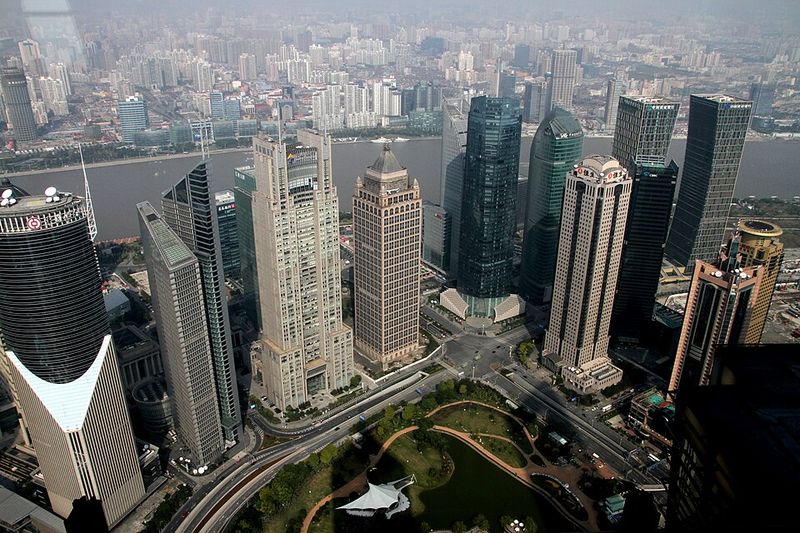

Shanghai: A Mega-City That Was Sinking at 17 Centimeters a Year

Shanghai ballooned into a megacity on a soft delta plain. By the late 1950s and early 1960s, subsidence hit around 17 centimeters per year in some periods.

Aggressive groundwater pumping pulled pressure from compressible soils near the Yangtze River delta.

That rate is alarming anywhere, but especially where land sits low and flood risk is naturally high. Infrastructure was not built for that pace of descent.

Shanghai’s scientists and planners documented the mechanism clearly and began a decades-long push to slow the fall. The numbers became a rallying cry: double-digit loss demanded a new playbook.

The city would not gamble its future on luck. It would change how water moved underground.

Shanghai’s Strategy Was More Complex Than Long Beach

Shanghai lacked a single oil field to manage. Its problem was diffuse groundwater extraction.

The response mixed policy and engineering: reduce pumping, shift withdrawals deeper, install recharge wells, and inject purified river water into target formations.

Over time, average subsidence fell toward about one centimeter per year. Still sinking, yes, but no longer in freefall.

That slower pace lets planners adapt drainage, rail tunnels, and seawalls more rationally.

The program’s strength was coordination. Utilities, hydrologists, and city leaders aligned monitoring with action.

Data guided where to inject and how much to cut withdrawals. It is not glamorous, but it is the kind of steady governance that keeps a megacity functional.

Why ‘Buying Time’ Might Be the Most Valuable Outcome

Stopping subsidence entirely is rare. Slowing it can be priceless.

A few centimeters preserved over a decade changes flood math, pump sizing, and insurance outcomes. It means stormwater stays on promenades instead of pouring into subway entrances.

That window lets cities phase upgrades intelligently.

Buying time is not defeatist. It is pragmatic resilience.

Coastal megacities juggle budgets, politics, and physics. Slower descent aligns projects with realistic timelines and avoids crisis-driven spending.

Engineers treat injection as a brake rather than a rewind button. The value appears in avoided losses and smoother transitions.

By stretching the calendar, a city can strengthen levees, reroute power, and protect hospitals before the next big storm arrives.

Injection Can Sometimes Lift Land – But Experts Don’t Oversell It

Yes, injection can produce measurable uplift in some formations. But sediments are not rubber.

Once grains rearrange tightly, much of that compaction is locked in. Mexico City shows minimal elastic rebound even when groundwater rises.

That reality keeps expectations honest.

Experts frame injection as stabilization first. Lift, if it happens, is a welcome bonus.

The primary success metric is slowing or halting downward trends, not recovering historic elevation.

Treating it like a brake avoids overpromising and underdelivering. Cities plan for today’s ground level, not yesterday’s.

That mindset drives better investments: floodgates aligned to current grades, foundations designed for present loads, and monitoring that catches drift early.

The Hidden Risk: Injecting Too Fast Can Trigger Earthquakes

Push pressure too quickly and the subsurface can push back. Faults and fractures thread through many basins.

If injection fronts meet stressed faults, small earthquakes may follow. Fluids can also migrate into unwanted layers, warping the ground or salinizing aquifers.

That is why modern programs throttle flow rates, target specific formations, and keep buffers from known structures. Engineers borrow techniques from petroleum and geothermal fields to manage pressure fronts responsibly.

Risk is managed, not ignored. Seismic networks, step-rate tests, and shutoff thresholds create guardrails.

The aim is a stable city above and a quiet reservoir below, with data steering clear of dangerous thresholds.

The New Surveillance Network Under Cities

Today, subsidence control is inseparable from measurement. Rooftop GPS arrays capture millimeter-scale motion.

Satellites using InSAR scan entire metros for subtle warping. Borehole sensors read pore pressures where it matters, not just at the surface.

These streams feed models that predict how layers will respond to each injection tweak. When a district drifts downward faster, operators adjust.

When pressure climbs near a fault, rates ease off. Feedback turns a risky guess into a controlled process.

The result is a nervous system for the ground beneath a city. It is not flashy, but it lets teams steer toward stability, catch anomalies early, and budget upgrades with confidence.

The Price Tag Problem: Water Injection Isn’t Cheap

Injection takes water, treatment, and lots of energy. Every cubic meter pressurized underground shows up on a bill.

That same water may be wanted for drinking, farms, factories, or rivers. Budgets and priorities collide fast.

Cities have to weigh avoided flood damage against operating costs. Some choose seasonal or targeted injection to stretch dollars.

Others bundle recharge with wastewater reuse, squeezing more value from each drop.

There is no free uplift. The economics work when protection of ports, transit, and hospitals justifies the watt-hours and pipeline miles.

Transparent accounting helps, showing citizens what stability costs and what disasters might cost without it.

Why This Matters More as the Planet Warms

Climate change stacks the deck. Seas rise while storms strengthen, squeezing low-lying districts.

Add subsidence, and effective elevation erodes from both sides. A city can lose altitude twice as fast as models predict if it ignores the ground’s motion.

That is why some researchers call subsidence a core climate risk factor. Managing extraction and recharge can reshape flood probabilities as much as seawalls or pumps.

Ignoring it leaves defenses miscalibrated.

In parts of China and beyond, planners now fold pore pressure management into resilience plans. It is not a silver bullet, but it shifts odds in a world tilting toward wetter, wilder storms.

The Real Goal: Turning Aquifers and Oil Fields Into ‘Hydraulic Supports’

Modern programs treat depleted aquifers and oil fields as potential supports. Restore enough pressure, and those layers behave like hydraulic beams under a metropolis.

The goal is not immortality. It is stability that slows the clock.

Engineers set pressure targets, install control valves, and nudge the subsurface toward equilibrium. It is systems engineering for geology: sensors, models, and conservative margins.

When successful, streets stay level, tunnels stay dry longer, and flood maps stop shifting so fast. That buy-in requires cross-agency cooperation and public trust, because the work is invisible and long-term.

Yet the payoff can be profound on the next storm’s worst day.

The Future of Coastal Cities Might Be Underground

Coastal defense usually makes us think of concrete and steel – seawalls, storm barriers, raised roads, protective dunes. But another layer of protection may be working quietly out of sight.

Beneath streets and subway stations, injection wells, pressure sensors, and groundwater models help stabilize the ground itself.

This underground system doesn’t replace pumps or wetlands; it supports them. By preventing the land from slowly sinking, it helps surface defenses do the job they were built for.

When it works, nothing dramatic happens – fewer surprise floods, fewer cracked pipes, fewer costly repairs. You barely notice it.

And that quiet reliability is what real resilience looks like.