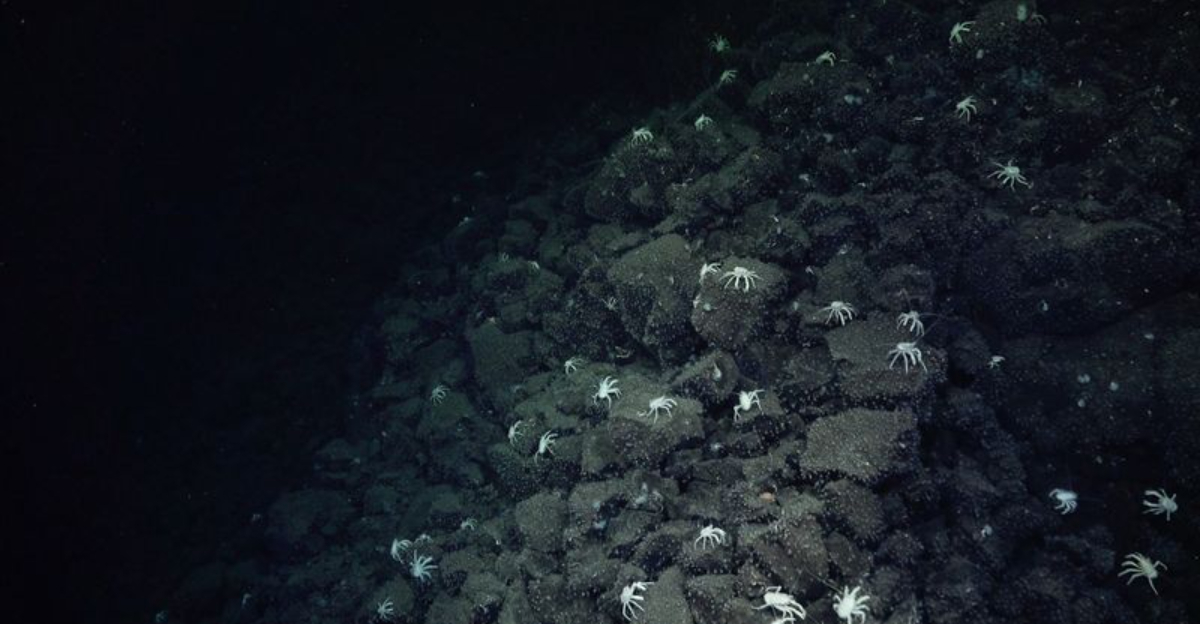

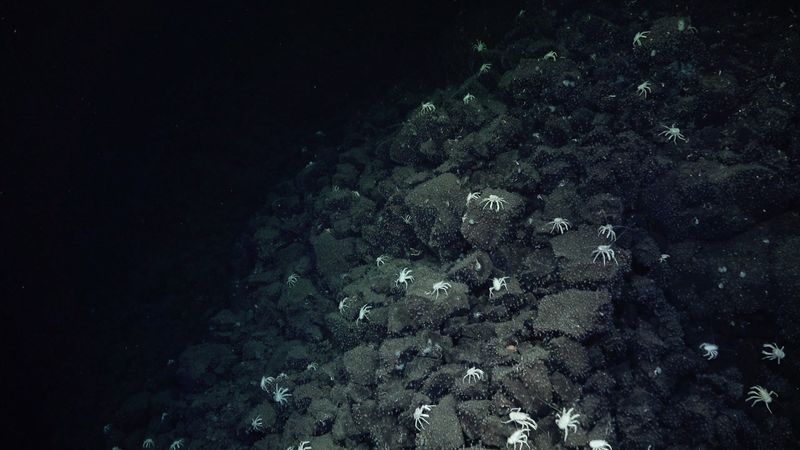

Deep beneath the Pacific Ocean, off the coast of the Galápagos Islands, scientists made an incredible discovery—and they had some unexpected guides. A trail of ghostly white crabs led researchers to a hidden hydrothermal vent field, a place where superheated water bursts from cracks in the seafloor. This find reveals how even the smallest creatures can unlock secrets of the deep sea.

Crabs Became Underwater Tour Guides

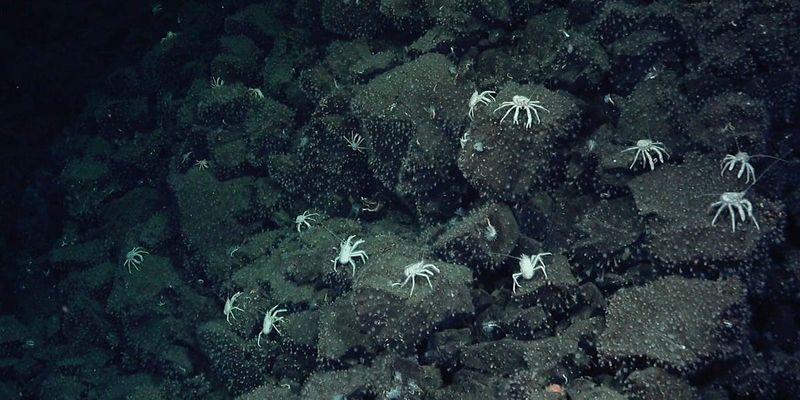

Marine biologists weren’t searching blindly when they found this underwater wonder. Galatheid crabs, also called squat lobsters, naturally flock to areas where warm, mineral-loaded water seeps from the ocean floor. These pale crustaceans act like living signposts, marking spots where vents create unique habitats.

Researchers deployed a remotely operated vehicle and followed increasing numbers of crabs through the darkness. The denser the crab populations became, the closer the team got to their target. Eventually, the crustaceans led them directly to a brand-new vent field, proving that sometimes nature’s own residents know the neighborhood better than any high-tech equipment.

A Field Named After Its Discoverers

Covering roughly 9,178 square meters—about the size of two football fields—this newly found vent field earned the name “Sendero del Cangrejo,” which translates to “Trail of the Crabs” in Spanish. The site honors the crustaceans that made the discovery possible.

Five towering chimney structures and three bubbling hot springs dot the area, with water temperatures soaring up to 288 degrees Celsius. That’s hot enough to melt lead! The field sits along the Galápagos Spreading Center, where two massive tectonic plates pull apart. Chemical clues first hinted at this location back in 2008, but it took years of detective work to pinpoint the exact spot.

Extreme Conditions, Extraordinary Life

You might think nothing could survive in such scorching, oxygen-starved water, but you’d be wrong. Scientists found giant tube worms swaying near the vents, some stretching several feet long. Massive clams the size of dinner plates clung to rocks, while clusters of mussels thrived in conditions that would kill most ocean creatures.

These organisms don’t rely on sunlight like surface dwellers. Instead, they use chemosynthesis, converting chemicals from the vent water into energy. This discovery reminds us that life finds ways to flourish in Earth’s most hostile environments, teaching us valuable lessons about adaptation and survival in extreme places.

Why This Discovery Matters

Hydrothermal vents represent biological treasure chests hidden thousands of feet below the surface. Each new vent field helps scientists understand how life evolved in Earth’s earliest oceans and how ecosystems function without sunlight. The Schmidt Ocean Institute collaborated with Ecuador’s Galápagos National Park, the Charles Darwin Foundation, and the Ecuadorian Navy to make this happen.

Finding these vents also matters for conservation. As deep-sea mining becomes more common, knowing where fragile ecosystems exist helps protect them. Did you know fewer people have visited these deep-sea vents than have walked on the moon? Every discovery opens doors to understanding our planet’s final frontier.