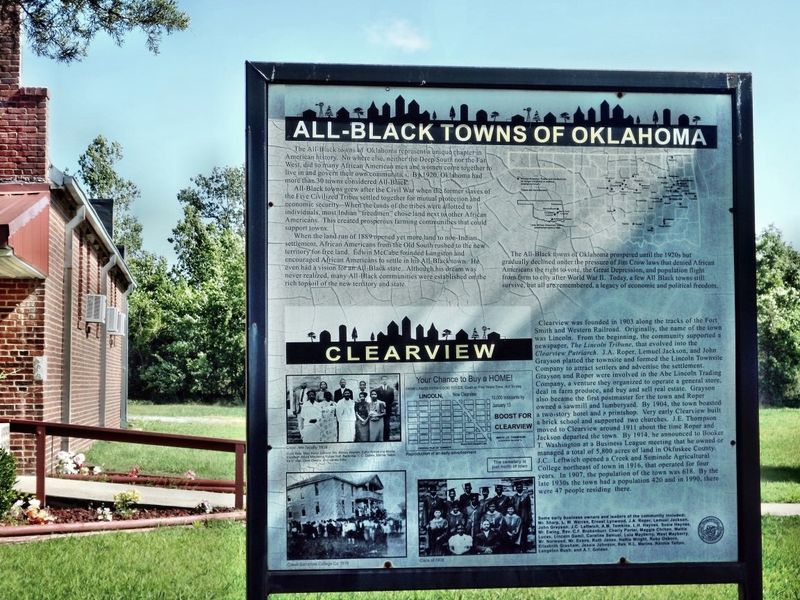

Clearview, Oklahoma, once thrived as a beacon of hope and independence for Black settlers in the early 1900s. Today, this tiny town of just 41 residents has nearly vanished from modern maps, yet its powerful story refuses to be forgotten.

From its roots as an all-Black freedmen’s settlement to its current status as a near-ghost town, Clearview represents a fascinating chapter of American history that deserves to be remembered.

Founded by Former Slaves Seeking Freedom

Former slaves and their descendants carved Clearview out of Oklahoma Territory in 1903, determined to build something entirely their own. The Lincoln Townsite Company platted the area originally as “Lincoln,” creating a safe haven where Black families could own land, govern themselves, and escape the oppressive Jim Crow laws spreading across the South.

Freedmen traveled from Texas, Arkansas, and other states, drawn by advertisements promising equality and opportunity.

These pioneers faced incredible challenges. They cleared dense forests, built homes from scratch, and established farms on unfamiliar soil.

Despite harsh weather, limited resources, and isolation, they persevered with remarkable determination.

The town represented more than just property ownership. It symbolized true freedom and self-determination for people who had been denied basic rights for generations.

Families could vote, hold office, and make decisions about their community without white interference.

By 1910, Clearview had grown to over 400 residents. The settlement proved that Black Americans could thrive independently when given the chance.

This founding spirit still echoes through the town’s remaining structures and in the memories of descendants who honor their ancestors’ courage.

One of Over 50 All-Black Towns in Oklahoma

Oklahoma Territory became an unlikely promised land for Black Americans between 1865 and 1920, hosting more all-Black towns than any other state. Clearview joined this remarkable network of communities including Boley, Taft, Langston, and Rentiesville, where African Americans could exercise full citizenship rights.

These towns emerged during a unique historical window when Oklahoma’s territorial status offered freedmen unprecedented opportunities before statehood brought restrictive laws.

Each settlement developed its own character and economy. Some focused on agriculture, others on commerce or education.

Clearview distinguished itself through farming and community solidarity, while neighboring towns like Boley became known for banking and business.

The concentration of Black towns created a powerful support network. Residents traded goods, shared resources, and helped each other during difficult times.

This interconnected community proved that Black self-governance could succeed on a large scale.

Sadly, most of these towns have disappeared or dwindled to tiny populations. Economic hardships, the Great Depression, and migration to urban centers drained these communities of their vitality.

Today, fewer than fifteen survive, making Clearview’s persistence all the more significant as a living reminder of this bold social experiment.

A Population That Plummeted from Hundreds to Dozens

Clearview’s population tells a story of dramatic decline that mirrors countless rural American towns. At its peak around 1920, the town bustled with approximately 500 residents who supported multiple businesses, churches, and schools.

The 2020 Census counted just 41 people, a staggering 92% decrease that transformed a thriving community into a near-ghost town.

The Great Depression hit rural Oklahoma especially hard. Dust Bowl conditions destroyed farms and forced families to seek work elsewhere.

Young people left for cities like Tulsa and Oklahoma City, seeking better education and job opportunities that Clearview couldn’t provide.

Each decade brought further losses. By 1960, the population had dropped below 100.

The 1980s and 1990s saw continued exodus as remaining businesses closed and services disappeared. Without a school, post office, or grocery store, families had little reason to stay.

Today’s 41 residents are mostly elderly, deeply attached to their ancestral land despite the hardships. They live in a town that feels frozen in time, surrounded by abandoned buildings and overgrown lots where neighbors once lived.

This demographic collapse raises urgent questions about whether Clearview can survive another generation or will finally fade completely from existence.

The Creek Freedmen Connection

Many Clearview settlers descended from Creek Freedmen, formerly enslaved people who had been held by members of the Creek Nation. Before the Civil War, some Native American tribes in Indian Territory practiced slavery, and when emancipation came, these newly freed individuals faced uncertain futures.

The Creeks and other tribes were supposed to grant their former slaves full citizenship and land rights, but implementation proved complicated and often unfair.

Creek Freedmen occupied a unique position in American society. They weren’t considered fully Creek by tribal members, yet white society also rejected them.

This dual marginalization made establishing independent Black towns especially appealing.

Clearview offered these families a place where their complex heritage didn’t matter. They could simply be free landowners and citizens.

Many brought farming knowledge and survival skills learned during their time with the Creek Nation.

The Creek Freedmen heritage remains visible in Clearview today. Some residents still maintain connections to both African American and Native American traditions.

This cultural blending created a distinctive community identity that set Clearview apart from other Black settlements. The struggle for Creek Freedmen rights continues in modern courts, making this historical connection more than just ancient history.

Main Street’s Vanished Businesses

Clearview’s Main Street once hummed with commerce that served both residents and travelers passing through. The town supported two general stores, a cotton gin, a blacksmith shop, several churches, a hotel, restaurants, and even a newspaper called the Clearview Patriarch.

Business owners took immense pride in their establishments, which proved Black entrepreneurship could flourish without white competition or interference.

The general stores stocked everything from farm equipment to fabric, serving as community gathering spots where neighbors exchanged news and gossip. The cotton gin processed crops from surrounding farms, providing crucial infrastructure for the agricultural economy.

The blacksmith kept wagons rolling and farm tools functional.

Saturday was market day when Main Street came alive. Farmers brought produce to sell, families shopped for weekly supplies, and children begged for penny candy.

The hotel housed visiting relatives and occasional travelers, while restaurants served home-cooked meals that brought people together.

Now, Main Street stands nearly empty. Most buildings have collapsed or been torn down, leaving vacant lots overgrown with weeds.

A few structures remain, their windows broken and roofs sagging, silent witnesses to busier times. The absence of commerce has erased Clearview’s economic heartbeat, leaving only memories and fading photographs of what once was.

The School That Educated Generations

Education stood at the center of Clearview’s identity and aspirations. The town’s school served students from first grade through high school, employing Black teachers who understood their students’ unique challenges and dreams.

Parents sacrificed enormously to keep their children in school, knowing education offered the best path to a better life.

The schoolhouse doubled as a community center. It hosted church services, town meetings, celebrations, and funerals.

Teachers commanded deep respect, often serving as advisors on matters beyond academics. The school library, though small, opened worlds of knowledge to children who might otherwise have limited access to books.

Sports brought the community together, especially basketball games that drew crowds from neighboring towns. School plays and music performances showcased student talents and provided rare entertainment in this isolated area.

Graduation ceremonies were major events, celebrated with pride and hope.

The school closed in the 1960s when consolidation forced students to attend larger schools in nearby towns. This closure devastated Clearview, removing a vital reason for families to stay.

Without their own school, the town lost its future. The empty building stood for years before eventually collapsing, taking with it countless memories of children who learned to read, dream, and aspire within its walls.

Churches That Still Stand Guard

While most of Clearview has crumbled, a few churches remain standing like faithful sentinels watching over the fading town. These simple wooden structures with their modest steeples represent the spiritual foundation that sustained residents through decades of hardship.

Faith provided comfort when crops failed, strength when neighbors moved away, and hope when the future looked bleak.

Churches served functions far beyond Sunday worship. They hosted community dinners, provided emergency shelter, and acted as informal social service agencies.

Pastors counseled troubled families, mediated disputes, and rallied the community during crises. Church ladies organized fundraisers and care for the sick and elderly.

Singing filled these sanctuaries every Sunday. Gospel hymns and spirituals connected worshippers to their ancestors and to each other.

The music expressed joy, sorrow, gratitude, and perseverance in ways words alone couldn’t capture. Visitors remember the powerful voices rising in harmony as one of Clearview’s most moving experiences.

Today, only a handful of elderly congregants still gather for services. The buildings need repairs that no one can afford.

Yet these churches refuse to surrender, standing as testaments to the faith that built Clearview and the determination that keeps its memory alive. They represent the town’s soul, enduring when everything else has faded.

The Cotton Economy That Sustained the Town

Cotton dominated Clearview’s economy from its founding through the mid-20th century. Families worked their small farms from sunrise to sunset, planting, chopping, and picking cotton by hand in Oklahoma’s unpredictable weather.

The annual cotton harvest determined whether families would eat well or struggle through winter, making every boll precious.

Clearview’s cotton gin processed the harvest, removing seeds and preparing fiber for market. This crucial facility meant farmers didn’t have to travel to distant towns, keeping money circulating within the community.

The gin’s seasonal operation provided employment and brought farmers together to share techniques and commiserate about prices.

Cotton prices fluctuated wildly, leaving farmers vulnerable to forces beyond their control. Good years brought modest prosperity; bad years meant debt and desperation.

The boll weevil infestation of the 1920s devastated crops across Oklahoma, hitting small Black farmers especially hard since they lacked financial reserves to weather the crisis.

Mechanization eventually made small cotton farms obsolete. Large operations with expensive equipment could produce more cotton with less labor, undercutting family farmers.

As cotton farming became unprofitable, Clearview lost its economic foundation. Fields once white with cotton now grow wild, reclaimed by prairie grasses and scrub trees, silent witnesses to the labor that once sustained a community.