Bolivia’s Salar de Uyuni holds more lithium than anywhere else on Earth, and that matters because lithium powers the batteries in electric cars, phones, and laptops. As the world rushes to mine this white gold, a serious environmental problem is quietly building beneath the shimmering salt flats.

Few people are talking about it, but the risks could affect wildlife, water, and the stunning landscape that draws tourists from across the globe.

1. The ‘world’s biggest’ claim is about the resource under Uyuni

Salar de Uyuni isn’t just another salt flat. Geologists estimate that beneath its crust lies the planet’s most massive concentration of lithium, a metal now critical to the battery revolution powering electric vehicles and renewable energy storage.

This Bolivian treasure sits at the heart of global supply-chain conversations, with governments and corporations eyeing it as a strategic asset that could reshape the balance of power in green technology.

What makes Uyuni stand out is sheer scale. The brine pooled underground across more than 4,000 square miles contains lithium concentrations that dwarf competing sites in Chile, Argentina, and Australia.

As demand for electric cars skyrockets, this remote corner of the Andes has become a geopolitical hotspot, drawing investment pitches, diplomatic missions, and industrial plans that promise jobs and revenue for one of South America’s poorest nations.

Yet size alone doesn’t guarantee smooth extraction. The same vastness that makes Uyuni valuable also complicates logistics, environmental oversight, and community relations.

Local leaders want control, environmentalists warn of fragile ecosystems, and mining engineers face technical puzzles unique to high-altitude salt chemistry. The world’s biggest lithium deposit is also becoming a case study in how resource wealth can create as many challenges as opportunities.

2. Uyuni’s beauty is part of the pressure

Every year, tens of thousands of visitors flock to Salar de Uyuni to witness one of nature’s most surreal spectacles. During the rainy season, a thin layer of water transforms the salt flat into a mirror that reflects the sky, creating dreamlike photos that flood social media and travel blogs.

Tour operators, local guides, and small hotels depend on this influx, building an economy around the landscape’s visual magic.

Mining threatens to disrupt that delicate balance. Industrial infrastructure—pump stations, evaporation ponds, processing plants, and access roads—carves permanent scars into terrain that tourists expect to find pristine.

Dust from heavy trucks, chemical odors from processing, and restricted access zones can all diminish the experience that travelers pay to see, potentially undermining a revenue stream that employs hundreds of families.

Environmental groups argue that Uyuni’s tourism value might actually exceed its mining potential over the long term, especially if extraction damages the reflective surface or pollutes surrounding wetlands. Local communities face a tough choice: embrace the promise of mining jobs and royalties, or protect a landscape that already generates income without the environmental risks.

Balancing these competing visions is becoming one of Bolivia’s most contentious policy debates.

3. The standard method starts by pumping brine up from underground

Lithium extraction at Uyuni begins far below the surface, where ancient brine sits trapped in porous layers of salt and sediment. Drillers bore wells down to depths that can reach 50 meters or more, tapping into salty groundwater that has accumulated lithium over millions of years.

Once the wells are in place, pumps lift this brine to the surface, where it flows into a network of pipes and channels leading to evaporation ponds.

The brine itself is a complex chemical soup. Along with lithium, it contains magnesium, potassium, boron, sulfate, and traces of other elements—including arsenic.

Engineers treat this mixture as raw ore, knowing that only a fraction of what comes up will eventually become battery-grade lithium carbonate. The rest is waste or byproduct, and managing that leftover chemistry is where environmental challenges begin.

Pumping rates matter. Extract too much brine too quickly, and underground pressures drop, potentially causing the land above to sink or altering the flow of water through surrounding wetlands.

Extract too slowly, and the economics don’t work—mines need volume to justify the cost of infrastructure. Finding the sweet spot requires constant monitoring, geological modeling, and regulatory oversight that isn’t always in place at remote, high-altitude sites.

4. Evaporation ponds ‘work’ by making the brine more extreme over time

Once brine reaches the surface, gravity guides it into a series of shallow ponds carved directly into the salt crust or lined with compacted earth. Sun and wind become the main tools of concentration: water evaporates, leaving behind salts that precipitate out in stages.

The brine flows from pond to pond, becoming saltier, more alkaline, and richer in lithium with each step.

This process isn’t fast. Depending on altitude, weather, and pond design, it can take months or even a year for brine to move through the entire sequence and reach the concentration needed for chemical processing.

During that time, the liquid changes color—from clear to amber to dark brown—as dissolved minerals accumulate and interact. Operators monitor salinity, temperature, and chemical ratios, adjusting flow rates to keep the system balanced.

What often goes unmentioned is that evaporation concentrates everything, not just lithium. Trace contaminants like arsenic, which might be harmless at low levels in deep brine, can multiply tenfold or more by the final pond.

That concentrated mixture becomes a hazard if it escapes containment, whether through leaks, overflow during storms, or accidents during transfer. The same natural process that makes lithium extraction economical also amplifies environmental risk.

5. The concentrate is turned into lithium carbonate (the battery workhorse)

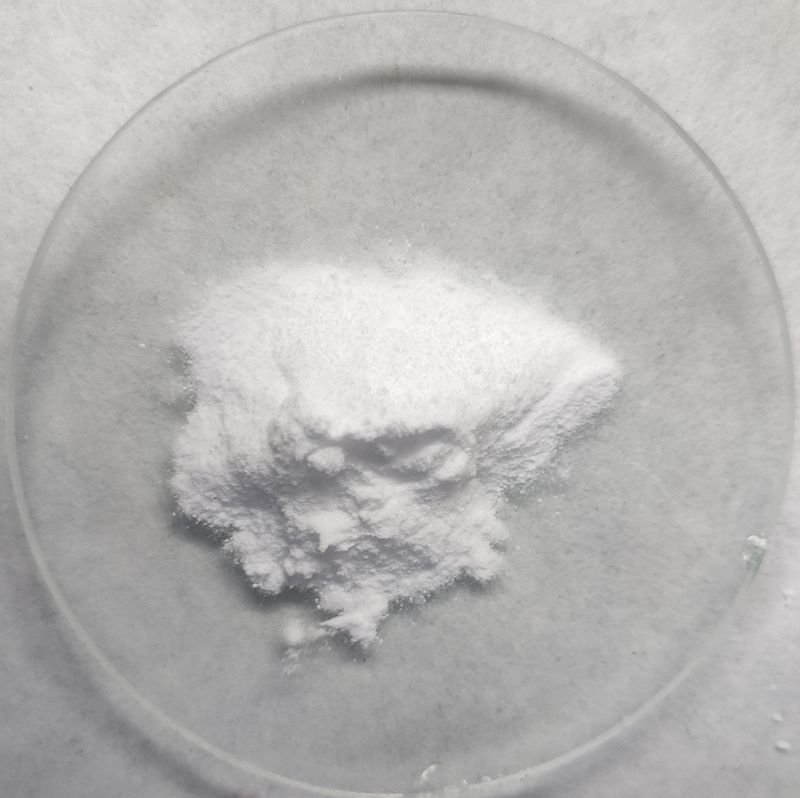

After months in the sun, the most concentrated brine finally enters a chemical plant where lithium is separated from the remaining salts and converted into lithium carbonate—a white powder that battery manufacturers buy by the ton. The process typically involves adding soda ash or lime to precipitate lithium out of solution, then filtering, washing, and drying the resulting crystals.

Quality control is strict: impurities can ruin battery performance, so the final product must meet tight specifications for purity.

Lithium carbonate is the industry standard because it’s stable, easy to transport, and compatible with most cathode chemistries used in lithium-ion batteries. From Uyuni, it might travel by truck to a Bolivian port, then by ship to factories in Asia, Europe, or North America, where it’s refined further or blended into battery pastes.

Each ton represents months of evaporation, chemical treatment, and quality testing.

But the conversion step generates its own waste streams. Spent process water, filter cakes, and off-spec batches all need disposal or recycling.

Some plants reinject waste brine underground; others store it in lined ponds or evaporation basins. How these wastes are managed—and what contaminants they carry—determines whether lithium production leaves a light footprint or a toxic legacy.

6. The hidden problem: natural brine can already contain arsenic

Long before mining begins, the brine beneath Uyuni carries arsenic. Sampling reported from the region found natural concentrations ranging from about 1 to 9 parts per million, levels that reflect the geology of the Andes, where volcanic rocks and hydrothermal activity can release arsenic into groundwater.

In untouched brine sitting quietly underground, those numbers aren’t necessarily dangerous—the arsenic stays dissolved and locked away from living organisms.

The trouble starts when that brine is pumped to the surface and exposed to air, sun, and industrial processes. Arsenic doesn’t evaporate with water; it stays in solution, accumulating as the brine concentrates.

What begins as a few parts per million can climb to levels that pose serious health and ecological risks if the brine escapes into the environment or contacts food webs.

Few mining companies advertise this baseline contamination. Promotional materials emphasize lithium reserves and economic opportunity, while environmental impact assessments sometimes downplay or omit arsenic data.

Yet understanding the natural arsenic load is critical for designing safe operations, because any failure in containment doesn’t just release industrial chemicals—it releases a naturally occurring toxin that has been artificially concentrated to hazardous levels. Transparency about what’s in the brine from day one is the first step toward responsible management.

7. As brine concentrates, acidity can spike hard

Chemistry shifts dramatically as brine moves through the evaporation sequence. Measurements from pilot operations show pH values plunging from near-neutral in fresh brine to around 3.2 in the most concentrated ponds, a level acidic enough to corrode some metals and alter the behavior of dissolved contaminants.

This acidity isn’t added intentionally; it results from the interplay of salts, carbonates, and trace elements as water evaporates and chemical equilibria shift.

Acidic brine behaves differently than neutral or alkaline brine. Metals like arsenic become more soluble and mobile, making them harder to remove or contain.

Acidic conditions can also degrade pond linings, accelerate corrosion of pipes and pumps, and complicate downstream processing. Operators must adjust treatment protocols, use acid-resistant materials, and monitor pH continuously to avoid equipment failures or unplanned releases.

The pH swing is a red flag for environmental managers. If acidic, arsenic-rich brine leaks onto the salt crust or seeps into shallow groundwater, it can create conditions where toxins spread more easily than they would in neutral water.

Birds, insects, and microbes adapted to the salar’s naturally alkaline environment may have little defense against sudden acid exposure. Keeping that chemistry contained isn’t just a technical challenge—it’s an ecological imperative that demands constant vigilance and backup systems.

8. Arsenic doesn’t ‘go away’ – it can become the headline risk

By the time brine reaches the final evaporation pond, arsenic concentrations can soar to nearly 50 parts per million, described in technical reports as “extremely high” in that operational context. That’s a tenfold or greater increase from the natural baseline, and it represents a toxicity threshold where even brief exposure can harm sensitive organisms.

Arsenic at these levels isn’t a trace contaminant anymore; it’s a dominant hazard that shapes how the entire operation must be managed.

Arsenic’s persistence is what makes it so dangerous. Unlike some pollutants that break down over time or bind tightly to soil, arsenic remains mobile and bioavailable, especially in the saline, alkaline, and sometimes acidic conditions of a salt flat.

If concentrated brine escapes—through a pond breach, pipe rupture, or mishandling during transfer—arsenic can spread across the landscape, infiltrate wetlands, or enter food webs, with effects that last for years.

Regulators and communities often focus on lithium’s economic promise, overlooking the arsenic shadow that follows every ton extracted. Yet arsenic exposure is a well-documented public health threat, linked to cancer, skin lesions, and developmental problems in humans, and to reproductive and neurological harm in wildlife.

Ignoring it doesn’t make it disappear—it just delays the reckoning until contamination is discovered, lawsuits are filed, or ecosystems collapse.

9. Leaks or releases don’t just stay in one place

Accidents happen. A pond liner tears, a valve fails, a storm overflows a containment basin, or a transfer hose ruptures during a shift change.

When concentrated, arsenic-laden brine escapes, it doesn’t pool neatly in one spot. On a salt flat, the crust is porous and fractured, allowing liquids to seep laterally and downward, spreading contamination across areas much larger than the original spill.

Wind and rain accelerate the spread. Wet brine can wick along salt crystals, evaporate and leave arsenic residue on the surface, or infiltrate shallow aquifers that feed nearby wetlands.

Birds walking across the crust pick up contaminated dust on their feet and feathers. Insects that breed in surface water ingest arsenic directly.

What starts as an industrial mishap quickly becomes a landscape-wide exposure pathway, with consequences that ripple through the food web.

Cleanup on a salt flat is notoriously difficult. There’s no soil to excavate, no vegetation to remove—just miles of crystalline crust that can’t be washed or scraped clean without destroying the very structure that holds the ecosystem together.

Once arsenic is loose, the best-case scenario is dilution over time, but in an arid environment where water is scarce, even that can take decades. Prevention is the only realistic strategy, yet many operations lack the redundancy and monitoring needed to catch problems before they become disasters.

10. Food webs can amplify the dose (even if water tests look ‘okay’)

Bioaccumulation is the silent multiplier that turns low-level contamination into a high-stakes crisis. Tiny organisms, microbes, algae, brine shrimp, absorb arsenic from water and sediment, concentrating it in their tissues at levels far exceeding what a simple water test would reveal.

As these organisms are eaten by larger animals, the arsenic moves up the food chain, accumulating further at each step. A flamingo feeding on contaminated shrimp can end up with arsenic loads many times higher than the pond water itself.

This means that water quality standards designed for human drinking water may not protect wildlife. A brine pond might test below a certain threshold for arsenic in the liquid phase, yet still devastate the local ecosystem through bioaccumulation.

Regulators who rely solely on water sampling miss the bigger picture: toxicity isn’t just about concentration in water, it’s about how contaminants move through living systems over time.

Monitoring food webs requires a different skill set—ecologists, not just chemists. It means sampling shrimp, insect larvae, algae, and bird tissues, then tracking trends over seasons and years.

Few lithium operations invest in that level of biological monitoring, leaving gaps in understanding that only become visible when populations crash or deformities appear. By then, the damage is done, and proving causation becomes a legal and scientific quagmire.

11. Even hardy brine shrimp have limits

Artemia franciscana, the brine shrimp that thrives in Uyuni’s hypersaline waters, is one of the toughest organisms on the planet. It can survive salt concentrations that would kill most aquatic life, endure temperature swings, and reproduce rapidly when conditions improve.

Yet lab tests show that even this extremophile has a breaking point: arsenic levels above about 8 parts per million start to reduce survival rates, and higher concentrations cause significant mortality.

That threshold is important because brine shrimp sit at the base of the salar’s food web. They feed on algae and bacteria, and in turn provide food for flamingos, migratory birds, and other species that depend on the salt flat ecosystem.

If arsenic stress reduces shrimp populations, the effects cascade upward, leaving predators with less to eat and forcing them to either move elsewhere or face starvation.

Mining operations that push arsenic concentrations beyond the shrimp’s tolerance zone are essentially dismantling the foundation of the local ecosystem. The landscape may still look pristine from a distance, but the biological engine that sustains wildlife is quietly failing.

Protecting brine shrimp isn’t just about saving a tiny crustacean—it’s about preserving the ecological integrity of one of the world’s most unique and fragile environments. Ignoring their limits is a gamble that could cost Uyuni its living heritage.

12. Flamingos and other wildlife can get hit indirectly

Three species of flamingo, Andean, Chilean, and James’s, breed and feed around the edges of Salar de Uyuni, drawn by the abundant brine shrimp and algae that thrive in the salty shallows. These iconic birds are already vulnerable, with populations pressured by habitat loss, climate shifts, and disturbance from tourism.

Adding arsenic contamination to that mix could tip the balance from manageable stress to population decline.

Flamingos don’t drink the concentrated brine, but they don’t need to. They filter-feed on shrimp and algae that have already accumulated arsenic through bioaccumulation, meaning the birds ingest the toxin with every meal.

Over time, arsenic can accumulate in their organs, impairing reproduction, weakening immune systems, and increasing mortality—especially in chicks, which are more sensitive to toxins than adults.

Other species face similar risks. Shorebirds, ducks, and raptors that visit the salar during migration depend on the same food web.

If brine shrimp populations crash or become toxic, these birds lose a critical stopover resource, potentially affecting migration success and breeding outcomes hundreds or thousands of miles away. The consequences of arsenic contamination at Uyuni don’t stay local—they ripple across hemispheres, linking a remote Bolivian salt flat to wetlands, coastlines, and conservation challenges far beyond South America.

13. Wastewater from processing plants is a different beast than pond brine

Once brine enters the chemical plant, it’s treated with reagents – lime, soda ash, acids, or bases – to precipitate lithium and remove impurities. These reactions generate wastewater with chemistry that can differ sharply from the evaporation pond brine.

Some streams are highly alkaline, with pH values above 10, while others are acidic or loaded with dissolved salts that didn’t precipitate as expected. Arsenic may still be present, along with new contaminants introduced during processing.

Managing this wastewater requires careful planning. Alkaline streams can mobilize certain metals, making them more likely to leach into groundwater if disposed of improperly.

Acidic streams can corrode storage tanks and pipelines, increasing the risk of leaks. And because the chemistry varies from batch to batch, operators need real-time monitoring and flexible treatment protocols to handle whatever comes out of the plant.

Disposal options are limited in a remote, high-altitude desert. Some plants evaporate wastewater in lined ponds, others attempt to neutralize and reinject it underground, and a few ship concentrated wastes off-site for disposal.

Each method has trade-offs: evaporation concentrates contaminants further, reinjection can clog aquifers, and off-site disposal is expensive and logistically complex. Without robust regulation and enforcement, the cheapest option often wins, even if it’s the riskiest for the environment.

14. ‘Just reinject it underground’ can backfire if done poorly

Reinjection sounds like an elegant solution: pump spent brine back into the aquifer where it came from, closing the loop and avoiding surface disposal. In theory, this returns water to the system, maintains underground pressure, and keeps contaminants away from wildlife.

In practice, reinjection can cause a host of problems if not carefully managed, from clogging injection wells to diluting remaining lithium reserves and spreading contamination into clean aquifers.

The main issue is chemistry. Spent brine has been concentrated, chemically altered, and exposed to air, changing its properties in ways that make it incompatible with the pristine brine still underground.

When the two mix, salts can precipitate and plug the porous rock, reducing permeability and forcing operators to drill new wells. Worse, if the reinjected brine contains arsenic or other contaminants, it can migrate laterally through the aquifer, reaching areas that were never part of the original mining footprint.

Successful reinjection requires detailed hydrogeological modeling, careful well design, and continuous monitoring of pressure, flow, and water quality. It’s not a cheap or simple fix, it’s an engineering challenge that demands expertise and investment.

Yet in the rush to extract lithium, some operators treat reinjection as an afterthought, injecting wherever it’s convenient and hoping for the best. That gamble can haunt them for decades, as contamination plumes migrate, wells fail, and communities downstream discover that their water has been compromised.

15. Pumping big volumes can physically reshape the land and water balance

Large-scale lithium extraction means pumping millions of liters of brine from underground every year. That volume doesn’t just disappear, it leaves behind voids and drops pressure in the aquifer, triggering physical changes that can spread far beyond the mine site.

One of the most serious is land subsidence, a slow sinking of the surface that happens when underground support is removed. Subsidence can crack roads, damage infrastructure, and alter drainage patterns, turning seasonal wetlands into dry basins or vice versa.

Water balance shifts are equally concerning. The brine aquifer beneath Uyuni is connected to a broader hydrological system that includes shallow freshwater lenses, springs, and wetlands used by wildlife and local communities.

Pumping can draw down water levels in these connected systems, drying out habitats, reducing forage for livestock, and forcing people to drill deeper wells or haul water from farther away. The effects can be subtle at first, a spring that flows a little less each year, a wetland that shrinks gradually—but they accumulate over time, reshaping the landscape in ways that may be irreversible.

Monitoring these impacts requires long-term data on groundwater levels, surface subsidence, and ecological indicators. Unfortunately, baseline data is often sparse in remote areas like Uyuni, making it hard to distinguish natural variability from mining-induced change.

By the time the evidence is clear, the damage may already be done, leaving communities and ecosystems to cope with a new, less hospitable reality.