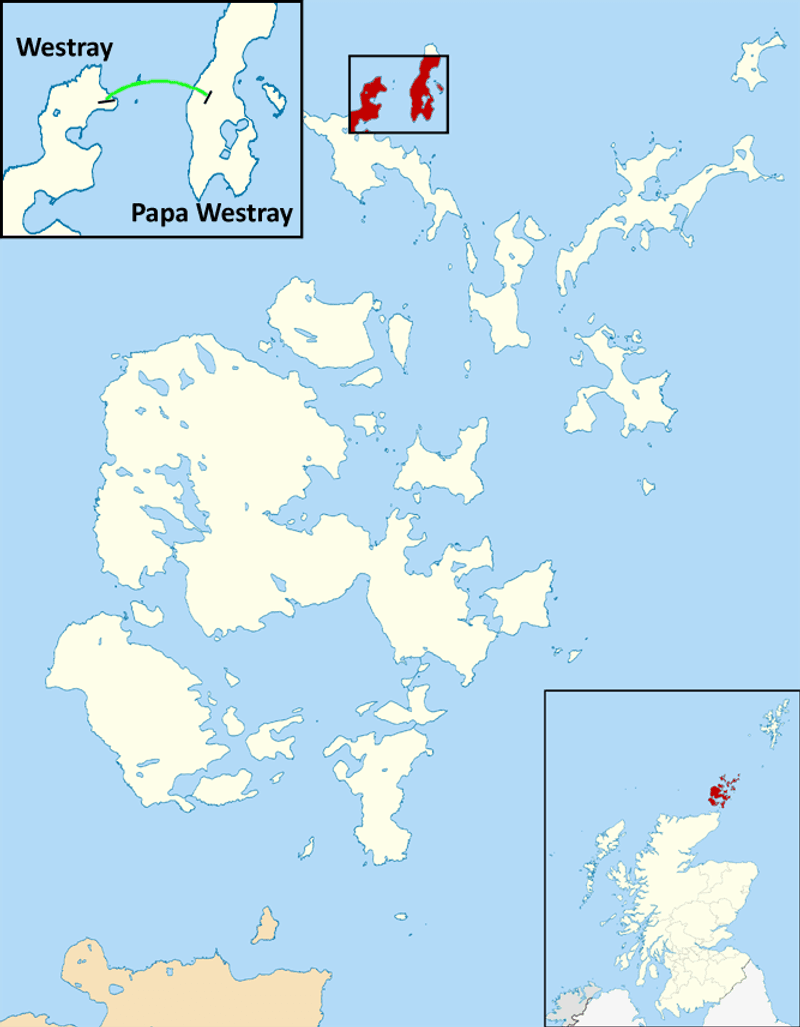

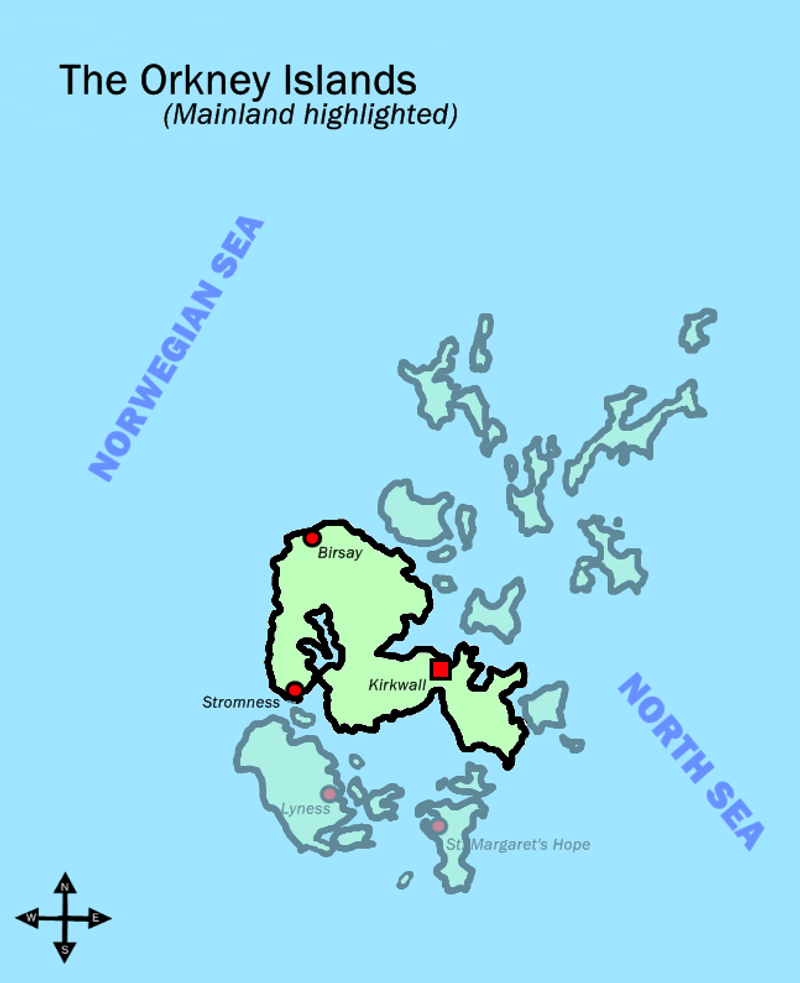

Boarding a plane in Scotland and landing before you have even settled into your seat sounds made up, but it’s real. Up in the Orkney Islands, there’s a scheduled flight so short it can be over faster than heating up popcorn. It runs between Westray and Papa Westray, covers just 1.7 miles, and holds the Guinness World Record for the shortest commercial air route on the planet. The wild part is how normal it feels.

You buckle up, the wheels leave the ground, and then you’re already touching down. That blink fast hop has become a bucket list experience for aviation fans and travelers who love brag worthy, offbeat adventures.

1. Meet the record-holder: the shortest scheduled passenger flight on Earth

Forget long-haul marathons across continents. The route linking Westray and Papa Westray in Scotland’s Orkney Islands holds the official Guinness World Record as the shortest scheduled passenger flight anywhere on Earth.

Covering a distance of just 2.74 kilometers (1.7 miles), this isn’t some one-time promotional gimmick or private charter for thrill-seekers.

Real passengers book real tickets, check in at real airports, and board actual commercial aircraft operated by Loganair, Scotland’s regional airline. The flight appears in booking systems just like any other route, complete with flight numbers, baggage allowances, and safety briefings.

What makes this route extraordinary is its combination of brevity and legitimacy. Many island-hopping services exist worldwide, but none can match this certified record for scheduled commercial aviation.

Passengers experience takeoff, a brief cruise at low altitude over shimmering sea, and landing—all within a timeframe shorter than most elevator rides in tall buildings.

The route serves communities that depend on reliable air connections year-round, making it both a practical lifeline and an aviation curiosity. Weather permitting, multiple flights operate daily, allowing islanders to commute for work, school, medical appointments, or shopping while giving visitors an unforgettable story to share.

2. The famous number: 53 seconds (but it’s not always that short)

That jaw-dropping 53-second figure gets repeated everywhere and yes, it’s absolutely real. Under perfect conditions with favorable winds, the flight between these Orkney islands has been completed in less than a minute, earning its place in record books and travel trivia everywhere.

Pilots have achieved this remarkable time when departing with tailwinds and executing a direct, efficient approach to landing.

However, most passengers shouldn’t expect their boarding passes to guarantee a sub-minute experience. Scheduled flight times typically range around 90 seconds, giving pilots appropriate margins for safety, weather variations, and standard operating procedures.

Wind direction, air traffic considerations, and seasonal conditions all influence actual flight duration.

Even when your particular flight takes two minutes instead of 53 seconds, the experience remains extraordinary. You’ll barely have time to glance out the window before descent begins.

Some passengers report feeling slightly cheated if they blink during the crucial middle section.

The variability actually adds to the route’s charm—will you get a record-breaking crossing or a more leisurely 120-second journey? Either way, you’ll land having experienced something genuinely unique in commercial aviation.

Frequent flyers on this route sometimes compare their times like golfers discussing course records, creating a friendly competition among regular commuters and repeat visitors.

3. It’s a lifeline, not a gimmick

While aviation enthusiasts and tourists flock here for bragging rights, this route exists primarily to serve isolated communities who need reliable transport options. Papa Westray has a population under 100 people, and without dependable connections to neighboring islands, daily life would become extraordinarily challenging.

Medical appointments, school attendance, grocery shopping, and employment opportunities all depend on maintaining links with larger islands.

The service operates under a Public Service Obligation (PSO) arrangement, meaning the government subsidizes routes that wouldn’t be commercially viable on their own but provide essential connectivity. This ensures flights continue even when passenger numbers don’t justify purely profit-driven operations.

Without this support, many Scottish island communities would face severe isolation, particularly during winter months when sea conditions can ground ferries for days.

Residents use these flights the way mainland folks use buses—casually, regularly, without fanfare. A shopkeeper might hop over to Westray for supplies, a student could commute for classes, or a patient might catch the morning flight for a medical consultation.

The aircraft essentially functions as a flying bridge, knitting together communities that geography has separated.

So while your Instagram post might frame this as a quirky travel experience, remember you’re participating in an essential public service that genuinely matters to people’s livelihoods and wellbeing.

4. The “Plan B”: the ferry ride is longer (but scenic)

Not everyone chooses to fly between these islands. A passenger ferry service connects Pierowall on Westray with Papa Westray, taking approximately 25 minutes each way according to scheduled timetables.

This maritime alternative offers its own rewards—time to breathe sea air, watch for wildlife, and experience the islands at a pace that feels more connected to their maritime heritage.

The ferry journey reveals perspectives impossible to appreciate from an aircraft. Seals often pop their curious heads above the water, seabirds wheel and dive around the vessel, and the changing light on the water creates ever-shifting moods.

Passengers can move around, chat with locals, and actually process the transition from one island to another rather than experiencing it as an instantaneous teleportation.

Weather plays a bigger role in ferry operations than flights. During storms, rough seas can delay or cancel sailings, while the aircraft often continues operating in conditions that would ground boats.

However, on calm, clear days, the ferry provides a meditative interlude that hurried air travelers miss entirely.

Some visitors deliberately choose the ferry for one direction and the flight for the other, maximizing their experience of inter-island transport. This combination offers the best of both worlds—the novelty of the record-breaking flight plus the scenic, relaxed ferry crossing that lets you truly absorb the landscape.

5. The plane is tiny and that’s part of the thrill

Forget wide-body jets with hundreds of seats and overhead bins. The Britten-Norman BN-2 Islander that typically operates this route carries fewer than ten passengers, creating an intimate flying experience that feels closer to a family car trip than commercial aviation.

This rugged, twin-engine workhorse was designed specifically for short island hops and rough airstrips, making it perfect for Orkney’s challenging conditions.

The aircraft’s small size means you’ll sit close to the pilots, sometimes close enough to watch instruments and hear radio communications. There’s no flight attendant service, no beverage cart, and certainly no in-flight entertainment system.

What you get instead is an unobstructed view of the sea, islands, and sky from windows that feel enormous relative to the cabin size.

First-time passengers sometimes experience mild anxiety about the plane’s diminutive proportions, but the Islander has an excellent safety record and handles beautifully in the gusty coastal winds that would trouble larger aircraft. Its high wings provide excellent visibility downward, and its slow cruising speed means you can actually identify features on the ground rather than watching a blurred landscape rush past.

The proximity to the elements—feeling every gust, hearing the engines clearly, seeing the water pass beneath—creates a visceral connection to flight that modern airliners have engineered away. You’ll remember this journey in ways you’d never recall a routine commercial flight.

6. Start with Westray: Pierowall’s cozy island vibe

Pierowall serves as Westray’s main settlement and offers everything visitors need for a comfortable island stay. With a population exceeding 550 residents, this village provides essential services including accommodation, dining options, and that intangible quality islanders call “crack”—the warm, unhurried social atmosphere that makes visitors feel immediately welcome rather than like tourists passing through.

The village curves around a sheltered bay where fishing boats bob gently at anchor. Walking the harbor wall at sunset, you’ll likely encounter locals who’ll happily share island stories, weather predictions, and recommendations for hidden spots tourists rarely discover.

This isn’t performative hospitality for visitors—it’s simply how island communities function when everyone knows everyone.

Pierowall lacks the commercial tourism infrastructure of mainland destinations. You won’t find chain hotels, souvenir megastores, or crowds jostling for selfie spots.

Instead, expect family-run guesthouses with home-cooked breakfasts, a community shop stocking essentials, and perhaps a pub where conversation flows more freely than anywhere you’ve recently experienced.

Many visitors initially worry that Westray might feel too quiet or remote. Within hours, that concern typically transforms into appreciation for a pace of life that prioritizes genuine human connection over constant stimulation.

Your phone might struggle for signal, but you’ll rediscover the lost art of actual conversation and the profound rest that comes from disconnecting completely.

7. Visit the Westray Heritage Centre for the island’s best stories

Westray Heritage Centre punches far above its weight for a small island museum. Located in Pierowall, this community-run facility preserves and presents the island’s rich archaeological and historical narrative through exhibits that bring millennia of human occupation to vivid life.

Even visitors who normally skip museums find themselves captivated by the quality of curation and the significance of artifacts on display.

The star attractions include the Westray Wife and Westray Stone—Neolithic carved stone figures that rank among Scotland’s most important prehistoric art pieces. The Westray Wife, a tiny carved female figure dating back roughly 5,000 years, represents one of the oldest depictions of a human face in British archaeology.

Her enigmatic expression has launched countless academic discussions and inspired contemporary artists.

Beyond these headline pieces, the center contextualizes Westray’s role in broader Orkney history. Exhibits cover everything from Viking settlements and medieval farming practices to the challenges of island life during both World Wars.

Knowledgeable volunteers often staff the center, providing insights and answering questions that printed labels can’t address.

Budget at least an hour here, preferably near the beginning of your Westray visit. Understanding the island’s deep history transforms subsequent explorations—suddenly those grassy mounds become ancient settlements, those stone walls tell stories of centuries past, and the landscape itself reveals layers of human presence stretching back to the Stone Age.

8. Explore the ruins of Noltland Castle

Noltland Castle rises from Westray’s landscape like something from a Gothic novel—all weathered stone walls, empty window frames, and the kind of atmospheric presence that makes history tangible. Built during the 16th century, this Renaissance fortress represents one of Scotland’s finest examples of fortified architecture from that period, despite its remote island location far from centers of power and wealth.

What immediately strikes visitors is the castle’s scale and ambition. This wasn’t a simple defensive tower but a sophisticated residence designed to impress and intimidate.

The walls bristle with gun loops—more than 70 of them—creating one of the most heavily defended structures in Scotland. Whoever commissioned Noltland Castle clearly expected trouble or wanted to project serious power across these islands.

Walking through the ruins, you can still trace the layout of grand halls, private chambers, and service areas. Stone stairs spiral upward to upper floors where panoramic views reveal why this location was chosen.

The sea approaches from one direction, while inland views would have given early warning of any threats approaching overland.

The castle remains unfinished, abandoned before completion under circumstances that historians still debate. That incompleteness adds to its haunting quality—a monument to ambitions that exceeded reality, standing sentinel over an island that has outlasted all the political dramas that once seemed so urgent to its builders.

9. Go to Noup Head for lighthouse views and seabird cliffs

Noup Head occupies Westray’s northwestern tip, where 76-meter cliffs plunge dramatically into the Atlantic Ocean. A lighthouse has marked this hazardous coast since 1898, guiding vessels through treacherous waters where powerful currents and hidden rocks have claimed numerous ships over centuries.

Standing at the cliff edge with wind buffeting from all directions, you’ll experience the raw power of Scotland’s northern coast in ways that sheltered locations can’t deliver.

During breeding season (roughly May through July), Noup Head transforms into one of Scotland’s premier seabird colonies. Tens of thousands of birds crowd the cliffs—guillemots, razorbills, kittiwakes, fulmars, and shags all competing for nesting ledges on the vertical rock faces.

The noise becomes overwhelming, a constant cacophony of calls echoing off stone and water.

Watching these birds navigate fierce winds and crashing waves demonstrates nature’s remarkable adaptations. They ride updrafts along the cliff face, plunge-dive for fish in turbulent seas, and somehow raise chicks on impossibly narrow ledges where one wrong move means disaster.

Photographers can spend hours here, capturing birds in flight against dramatic skies or documenting the chaotic energy of the colony.

The walk to Noup Head from the nearest parking area takes about 20 minutes across grassy headlands. Bring windproof clothing regardless of how calm conditions seem inland—coastal winds here can knock you sideways, and weather changes rapidly.

10. Puffin alert: Castle o’ Burrian (seasonal, but iconic)

Castle o’ Burrian isn’t actually a castle—it’s a dramatic sea stack rising from the waters off Westray’s coast, connected to the island by a narrow strip that becomes impassable at high tide. During puffin breeding season, this location becomes one of Orkney’s most reliable spots for close encounters with these charismatic seabirds, whose colorful beaks and comical waddling gait have made them conservation icons and tourist favorites worldwide.

Puffins arrive at their breeding colonies in April and remain through July or August, spending the rest of the year far out at sea. They nest in burrows dug into the grassy slopes above the cliffs, creating underground nurseries where they raise single chicks.

Adults commute constantly between their burrows and fishing grounds, returning with beaks full of small fish arranged neatly crosswise.

What makes Castle o’ Burrian special is the accessibility. Puffins here tolerate careful human observers at remarkably close distances, allowing photography and observation that would be impossible at more disturbed colonies.

Visitors who remain still and quiet can watch puffins land, waddle to burrow entrances, and engage in their elaborate courtship displays.

Timing your Westray visit for puffin season requires advance planning and some flexibility. Weather, food availability, and other factors influence exact arrival and departure dates each year.

Local accommodations and the heritage center can provide current information about whether puffins have returned and which locations currently offer the best viewing opportunities.

11. Don’t skip the beaches, yes beaches

Orkney beaches shatter expectations. Most visitors arrive imagining cold, rocky coastlines unsuited for anything but dramatic photographs.

Instead, they discover sweeping expanses of pale sand, water that glows turquoise under certain light conditions, and a wild beauty that rivals tropical destinations, minus the crowds, heat, and commercialization.

The Bay of Tafts on Westray exemplifies this unexpected coastal splendor. White sand stretches in a generous curve, backed by dunes and machair (the flower-rich grassland unique to Scotland’s northern and western coasts).

On calm days with clear skies, the water takes on colors that seem impossible at this latitude. Even in less ideal weather, the beach possesses a stark magnificence that makes you feel profoundly alive.

Swimming remains an option for the brave or wetsuit-equipped. Water temperatures rarely climb above refreshing, and currents require respect, but many visitors paddle at the water’s edge or simply walk for miles with only seabirds for company.

The beaches see so little traffic that footprints often remain undisturbed for hours, creating a sense of discovery that’s increasingly rare in our crowded world.

Coastal walks connecting various beaches reveal constantly changing perspectives—sea stacks, rock formations, hidden coves, and viewpoints that frame neighboring islands. Pack waterproofs and warm layers even in summer, because weather can shift dramatically, transforming a pleasant beach stroll into a character-building adventure.

12. Touch deep time on Papa Westray: the Knap of Howar

Papa Westray (affectionately called “Papay” by locals and frequent visitors) may be tiny, but it packs extraordinary historical significance into its modest landscape. The island’s population hovers around 90 residents, yet it preserves some of northern Europe’s most important Neolithic sites, including the Knap of Howar, two remarkably intact stone houses that predate Stonehenge and the Egyptian pyramids.

Standing before these structures triggers a profound temporal vertigo. The Knap of Howar dates to approximately 3700-3100 BCE, making these dwellings over 5,000 years old and among the oldest preserved stone buildings in northwest Europe.

Unlike monuments or temples, these were actual homes where families cooked meals, slept, raised children, and went about daily life when human civilization was still young.

The preservation level astonishes archaeologists and casual visitors alike. You can see stone furniture, hearths, storage areas, and doorways that connected the two structures.

The buildings used sophisticated drystone construction techniques, with walls still standing to significant height after five millennia. Imagine the hands that placed each stone, the lives lived within these walls, the conversations and dreams and fears of people separated from us by vast spans of time yet fundamentally similar in their human needs.

The site sits near the shore, exposed to weather that has somehow failed to erase it. Interpretive signage provides context, but the structures speak for themselves—humbling reminders of human persistence and ingenuity.

13. Step into early Christianity at St Boniface Kirk

St Boniface Kirk represents a completely different era of Papa Westray’s layered history. While the Knap of Howar speaks to Neolithic settlement, this church site documents the arrival and persistence of Christianity in Scotland’s far north.

The current structure incorporates medieval fabric, though the site’s religious significance stretches back much further, possibly to the 8th century when Irish monks established early Christian communities throughout Scotland’s islands.

The church building itself, though partially ruined, retains enough structure to convey its original form and purpose. Stone walls frame what was once the nave, and architectural details reveal construction techniques and aesthetic preferences from medieval Scotland.

The surrounding graveyard contains weathered headstones marking generations of island families, creating a tangible connection between past and present communities.

What makes St Boniface Kirk particularly atmospheric is its isolation and the sense of continuity it represents. Christianity reached these remote islands surprisingly early, and despite their distance from major religious centers, communities maintained faith traditions through centuries of change, hardship, and uncertainty.

The church became a focal point not just for worship but for social cohesion and cultural identity.

Visiting during golden hour, when low sun illuminates the stone and long shadows stretch across the graveyard, the site achieves an almost transcendent quality. You don’t need religious faith to appreciate the spiritual weight of a place where people have gathered for over a millennium, seeking meaning, comfort, and community.