America’s landscape is dotted with towns that feel like portals to another time. From Spanish colonial streets to Victorian-era villages, these historic destinations preserve architectural treasures and cultural traditions from centuries past. Whether you’re a history enthusiast or simply seeking a charming getaway, these 15 towns offer authentic glimpses into America’s rich and diverse heritage.

Williamsburg, Virginia — Colonial Life Recreated

Colonial Williamsburg represents far more than preserved buildings—it’s America’s premier living history experience. Spanning 301 acres, this meticulously recreated 18th-century town brings the colonial era to life through immersive demonstrations and authentic period details. Costumed interpreters don’t just dress the part; they embody the roles of blacksmiths, tavern keepers, and revolutionary thinkers.

As you stroll down Duke of Gloucester Street, the sounds of hammering metal and colonial-era music transport you backward in time. Period shops line the thoroughfare, their windows displaying goods crafted using traditional methods. You might encounter Thomas Jefferson debating politics or watch a cooper fashioning wooden barrels by hand.

The town’s commitment to historical accuracy extends to every detail. Buildings stand exactly where their originals once did, reconstructed using 18th-century techniques and materials. Gardens flourish with heirloom varieties of vegetables and flowers that colonial residents would have cultivated.

Educational programs throughout Williamsburg blur the boundaries between spectator and participant. Visitors can try their hand at colonial trades, taste period recipes, and engage in conversations about the ideas that sparked the American Revolution. This isn’t just a museum—it’s a doorway into the daily realities of early American life.

Galena, Illinois — Victorian Streets and Presidential Roots

Tucked into the rolling hills of northwest Illinois, Galena flourished during the 19th-century mining boom that gave the town its name—derived from the Latin word for lead sulfide. At its peak, this prosperous community produced nearly 85 percent of the world’s lead, attracting entrepreneurs and craftsmen who built the magnificent Victorian structures that still define the town today.

Main Street showcases some of the finest Victorian-era commercial architecture in the Midwest. Ornate ironwork adorns balconies and storefronts, while painted brick facades display the wealth that mining prosperity brought. Today, these historic buildings house boutique shops, art galleries, and cafés that maintain the town’s 19th-century character.

Galena’s most famous resident, Ulysses S. Grant, lived here before and after his presidency. The Italianate mansion gifted to him by grateful citizens in 1865 remains beautifully preserved, offering tours that reveal both presidential history and Victorian domestic life. Grant’s presence elevated Galena’s status, though nine other Civil War generals also called this town home.

Walking Galena’s broad avenues today feels remarkably similar to stepping into the 1800s. The town’s skyline remains largely unchanged, with church steeples and historic buildings creating a silhouette that echoes its mining heyday.

Harpers Ferry, West Virginia — Rivers & Revolutionary History

Geography and history converge dramatically at Harpers Ferry, where the Potomac and Shenandoah rivers meet amid steep, forested hills. This strategic location made it vital for early American industry and later, a flashpoint in the events leading to the Civil War. Thomas Jefferson once stood at this spot and declared the view worth crossing the Atlantic to witness.

The town’s restored 19th-century buildings cluster along narrow streets that climb from the riverbanks. Cobblestones worn smooth by countless footsteps lead past former armory buildings, merchant shops, and workers’ homes that now comprise Harpers Ferry National Historical Park. Each structure tells part of the larger story of American industry and conflict.

John Brown’s 1859 raid on the federal armory here became a defining moment in pre-Civil War tensions. Brown’s attempt to spark a slave rebellion failed, but it intensified the divisions that would soon tear the nation apart. The firehouse where Brown made his last stand still stands, a stark reminder of that pivotal October night.

Beyond its dramatic history, Harpers Ferry captivates with natural beauty. Hiking trails wind through surrounding hills, offering panoramic views of the river confluence below. The combination of preserved architecture, profound history, and stunning landscapes makes this town uniquely compelling.

St. Augustine, Florida — Spain’s Legacy on the Atlantic

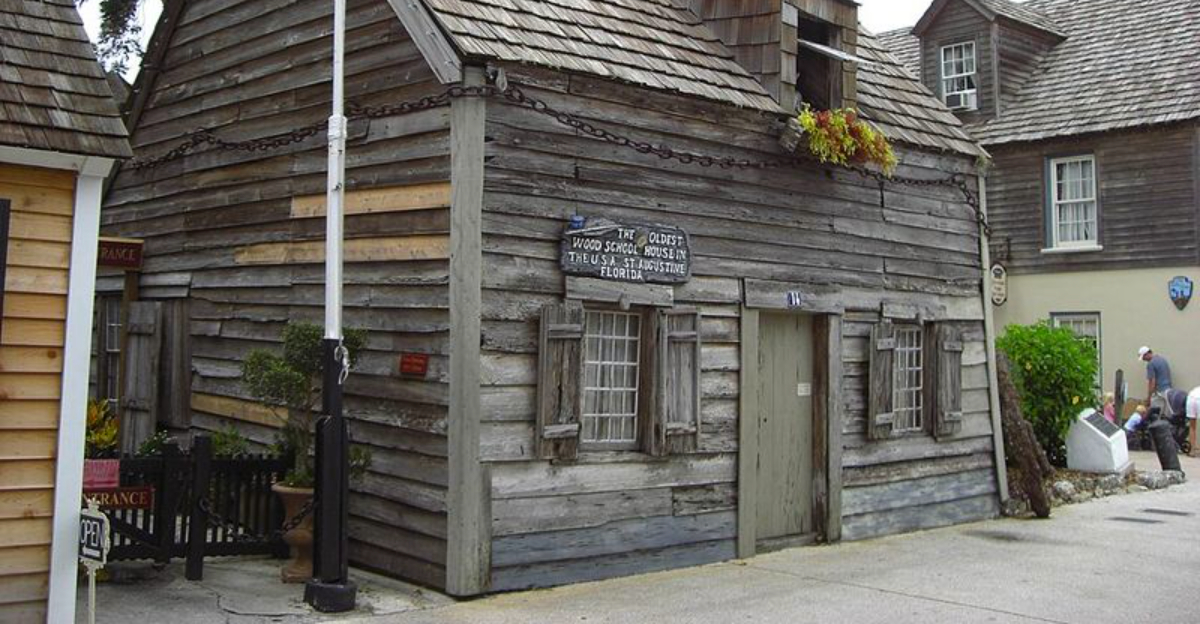

Founded in 1565 by Spanish explorers, St. Augustine holds the distinction of being the oldest continuously inhabited European settlement in the continental United States. Centuries before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock, Spanish conquistadors were already building fortifications and establishing communities along Florida’s Atlantic coast.

Walking through the historic district feels like crossing into another era entirely. Narrow cobblestone streets wind past Spanish colonial buildings painted in warm earth tones, their balconies draped with flowering vines. Spanish moss hangs from ancient oak trees, creating natural curtains that filter the subtropical sunlight.

The Castillo de San Marcos stands as the crown jewel of St. Augustine’s historic sites. This 17th-century stone fortress overlooks Matanzas Bay, its coquina walls having withstood centuries of storms and sieges. Inside, you can explore dark corridors and climb to ramparts where Spanish soldiers once kept watch.

Beyond the fortress, the town’s historic lanes invite leisurely exploration. Colorful shops occupy buildings that have stood for generations, selling everything from handcrafted goods to authentic Spanish cuisine. Every corner reveals another architectural detail or historical marker, making St. Augustine a living testament to Spain’s enduring influence on American history.

Mystic, Connecticut — Maritime Village With Old-World Appeal

Mystic’s identity has always been inseparable from the sea. This Connecticut coastal town built its reputation and fortune on shipbuilding, producing some of the finest vessels that sailed American waters during the 19th century. The whaling industry and clipper ship trade brought prosperity that’s still visible in the town’s well-preserved architecture.

Mystic Seaport Museum stands as the nation’s leading maritime museum, preserving an entire 19th-century coastal village. Historic sailing ships bob at wooden docks where visitors can board and explore. The Charles W. Morgan, America’s last surviving wooden whaling ship, serves as the collection’s centerpiece, her weathered hull telling stories of decades at sea.

Throughout the seaport, artisan workshops demonstrate traditional maritime crafts. Shipwrights shape wooden planks using hand tools, rope makers twist fibers into sturdy lines, and coopers craft the barrels essential for long sea voyages. These aren’t mere demonstrations—they’re preservation of skills passed down through generations.

Downtown Mystic extends the historic atmosphere beyond the seaport. Brick buildings dating to the 1800s line the streets, housing waterfront restaurants and shops. The iconic Mystic River Bascule Bridge, built in 1922, still opens regularly to allow tall ships passage, connecting the town’s past directly to its present.

Charleston, South Carolina — Antebellum Grace and Cobblestone Streets

Charleston wears its 350-year history with remarkable grace. Founded in 1670, this coastal city became one of the wealthiest and most cultured in colonial America, a prosperity reflected in the extraordinary architectural heritage that survived wars, earthquakes, and hurricanes. Walking these streets means encountering layer upon layer of American history.

The Historic District preserves one of the nation’s finest collections of antebellum architecture. Grand mansions with double-tiered piazzas line streets shaded by live oaks dripping with Spanish moss. These distinctive side porches weren’t just architectural flourishes—they captured cooling breezes from the harbor, a practical adaptation to Charleston’s subtropical climate.

Cobblestone streets and narrow alleys create an intimate scale that invites exploration on foot. Rainbow Row’s pastel-painted Georgian houses form one of America’s most photographed streetscapes. Historic churches—the city counts over 400—earned Charleston its nickname, the Holy City, their steeples creating a distinctive skyline.

Horse-drawn carriage tours remain popular for good reason, offering perspectives on architecture and history while moving at a pace appropriate to the surroundings. Guides share stories of Revolutionary War battles, devastating fires, and the diverse cultures—African, European, and Caribbean—that blended to create Charleston’s unique character and enduring charm.

Savannah, Georgia — Oaks, Squares & Southern History

General James Oglethorpe planned Savannah in 1733 using an innovative grid system centered on public squares—a design so successful that it’s still studied by urban planners today. Twenty-two of the original squares survive, each a green oasis shaded by massive live oaks whose branches create natural canopies draped with ethereal Spanish moss.

Savannah’s Historic District covers 2.5 square miles, making it one of the largest urban historic districts in the United States. Within this area, architectural styles span centuries, from colonial-era structures to ornate Victorian mansions. The continuity of preservation means you can walk blocks without encountering modern intrusions, maintaining an authentic sense of the past.

Jones Street frequently appears on lists of America’s most beautiful streets, and one stroll explains why. Antebellum homes with pristine facades line both sides, their gardens hidden behind wrought-iron fences. The street’s brick pavement and gas-style lamps complete the time-capsule atmosphere, though the lamps now burn electricity rather than gas.

The riverfront district adds another dimension to Savannah’s historic character. Converted cotton warehouses now house restaurants and shops, their thick walls and exposed beams reminding visitors of the port’s commercial heritage. Factor’s Walk, with its iron bridges connecting buildings at different levels, showcases the ingenious architecture merchants used to move goods from ships to storage.

Solvang, California — Danish Village in the American West

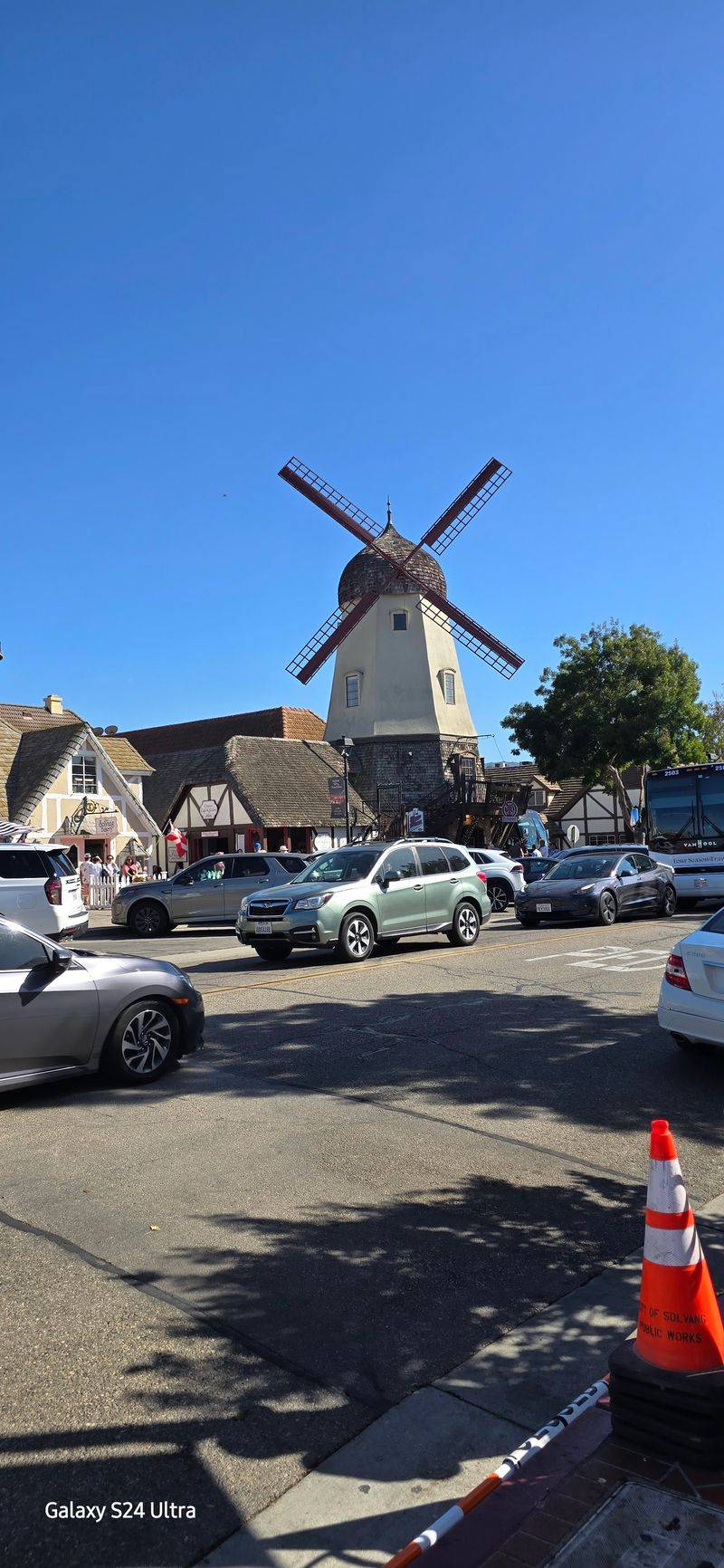

Spotting windmills and half-timbered buildings in the California sunshine creates delightful cognitive dissonance—until you learn Solvang’s story. Danish immigrants founded this town in 1911, deliberately creating a community that preserved their homeland’s architectural traditions and cultural practices. The name itself means “sunny field” in Danish, perfectly describing the Santa Ynez Valley location.

Strolling Solvang’s streets feels like wandering through a European village that somehow materialized in Southern California. Buildings feature the distinctive half-timbered construction of Danish architecture, their stucco walls accented with dark wooden beams in geometric patterns. Copper-topped towers and shake roofs complete the Old World aesthetic, while flower boxes overflow with colorful blooms.

Authentic Danish bakeries form the heart of Solvang’s cultural preservation. The aroma of fresh aebleskiver—spherical Danish pancakes dusted with powdered sugar—draws visitors into shops where traditional recipes have been passed down through generations. Pastry cases display kringle, Danish butter cookies, and other treats that would be at home in Copenhagen.

The town celebrates its heritage through festivals and traditions that keep Danish culture vibrant. Annual events include Danish Days, featuring folk dancing, music, and traditional costumes. Even the streetlights incorporate Danish design elements, ensuring that every detail reinforces Solvang’s unique character as America’s Danish capital.

New Hope, Pennsylvania — Quaint Riverfront History

Artists and writers discovered New Hope in the early 20th century, recognizing something special in this Delaware River town that others had overlooked. The community they built transformed New Hope into a creative haven while preserving the 18th and 19th-century architecture that first attracted them. Today, that artistic legacy continues alongside careful historic preservation.

Main Street’s collection of antique shops reflects both the town’s age and its longtime appeal to collectors and connoisseurs. Buildings that once housed mills and mercantile operations now display furniture, artwork, and curiosities spanning centuries. Browsing these shops becomes a treasure hunt through American material culture.

The Bucks County Playhouse, operating since 1939 in a converted 1790 gristmill, represents New Hope’s theatrical tradition. Major Broadway shows have premiered on this intimate stage, and the venue continues hosting productions that draw audiences from across the region. The playhouse’s history illustrates how historic buildings can be adapted for new purposes while maintaining their character.

Walking from the riverfront toward town center, you pass buildings with plaques noting their construction dates—many predating the American Revolution. Historic inns offer accommodations in rooms where travelers have stayed for over two centuries. The Delaware Canal towpath provides scenic walking along waterways that once moved goods to Philadelphia, connecting present-day recreation with past commerce.

Deerfield, Massachusetts — Colonial New England Preserved

Deerfield’s history stretches back to 1673, though its most dramatic chapter came in 1704 when a French and Native American raid devastated the settlement. The survivors rebuilt, and remarkably, many of those 18th-century structures still stand along The Street, Deerfield’s mile-long main thoroughfare. This continuity makes Deerfield exceptionally valuable for understanding colonial New England life.

Historic Deerfield operates as both a living community and an outdoor museum. Eleven house museums open their doors to visitors, each meticulously preserved or restored to represent different periods and aspects of colonial life. The collections inside these homes include some of the finest examples of early American furniture, textiles, and decorative arts.

The architecture itself tells stories about colonial values and priorities. Central chimneys provided efficient heating, while small windows conserved warmth—practical adaptations to New England winters. Simple, elegant lines reflected both Puritan aesthetics and the limitations of hand tools and local materials.

Gardens surrounding the historic homes grow heirloom varieties of vegetables, herbs, and flowers that colonial residents would have cultivated. These aren’t decorative additions but functional elements that demonstrate how families fed themselves and produced medicines. Walking through Deerfield’s preserved landscape offers immersive education about self-sufficient colonial life that textbooks cannot match.

Fredericksburg, Texas — German Heritage on the Frontier

German immigrants arrived in the Texas Hill Country during the 1840s, bringing architectural traditions and cultural practices from their homeland. Baron Ottfried Hans von Meusebach led settlers who founded Fredericksburg in 1846, negotiating a remarkable peace treaty with Comanche tribes that allowed the community to flourish. That German influence remains powerfully evident throughout the town today.

Main Street’s architecture reflects the fusion of German building traditions with Texas materials and climate. Limestone and brick structures feature the solid, practical construction Germans favored, adapted to accommodate the region’s heat. Fachwerk—traditional half-timbered construction—appears on several buildings, creating visual links to villages in Bavaria and other German regions.

German cultural preservation extends beyond architecture into living traditions. Restaurants serve authentic German cuisine—schnitzel, sauerkraut, and sausages—alongside Texas barbecue. Bakeries produce strudels and pretzels using recipes preserved through generations. The town’s Oktoberfest celebration draws thousands who come to enjoy German beer, music, and folk dancing in an authentically German Texas setting.

The Pioneer Museum complex preserves multiple historic structures, including an authentic Sunday House—small town homes that rural German families used during weekend trips to attend church and conduct business. These distinctive buildings represent practical adaptations to frontier life while maintaining cultural identity, perfectly symbolizing Fredericksburg’s unique blend of German heritage and Texas character.

Mackinac Island, Michigan — A Car-Free Time Capsule

Automobiles have been banned on Mackinac Island since 1898, a decision that seemed quaint then but now preserves an atmosphere increasingly rare in modern America. Transportation by horse-drawn carriage, bicycle, or foot creates a pace and soundscape that feels genuinely historic. The clip-clop of hooves on pavement and the absence of engine noise transport visitors to a gentler era.

Victorian architecture dominates the island, reflecting its late 19th-century heyday as a summer resort destination. The Grand Hotel, with its 660-foot-long porch overlooking the Straits of Mackinac, epitomizes Victorian grandeur. Built in 1887, it maintains period details from furnishings to formal dining traditions that make guests feel like time travelers.

Fort Mackinac crowns the bluff above town, its whitewashed stone walls and colonial-era buildings overlooking the harbor. British soldiers built the fort in 1780, and it played roles in the Revolutionary War and War of 1812. Today, costumed interpreters demonstrate military life from those periods, firing cannons and drilling in formations that echo across centuries.

Downtown’s shops and restaurants occupy Victorian-era buildings that have served visitors for over a century. The island’s famous fudge shops continue traditions begun in the 1880s, when confectioners discovered tourists enjoyed watching candy-making demonstrations. Wandering these streets, with their gingerbread trim and painted ladies, creates an immersive Victorian experience unmatched elsewhere.

Beaufort, South Carolina — Lowcountry History & Live Oaks

Beaufort’s history dates to 1711, making it one of South Carolina’s oldest towns, though Native Americans and Spanish explorers knew the area centuries earlier. The town’s strategic coastal location brought prosperity through maritime trade and Sea Island cotton cultivation, wealth reflected in the grand antebellum homes that still grace the waterfront and historic streets.

Live oaks define Beaufort’s visual character as much as any building. These massive trees, some centuries old, create cathedral-like canopies over streets and squares. Spanish moss drapes from their branches in silvery curtains that sway with coastal breezes, adding an ethereal quality to the already romantic setting.

The waterfront historic district preserves exceptional examples of antebellum architecture. Grand homes with double-tiered porches face the Beaufort River, their positions chosen to capture cooling breezes. Many feature Beaufort’s distinctive “Beaufort style”—raised foundations, tall windows, and tabby construction using oyster shells mixed with lime and sand, materials abundant in the Lowcountry.

Walking tours reveal layers of history beyond architecture. Beaufort played significant roles during the Revolutionary War and Civil War, and the town’s African American heritage—particularly Gullah culture—adds profound depth to the historical narrative. Former plantations, now preserved as parks and museums, provide sobering education about the enslaved people whose labor built the wealth that created Beaufort’s architectural legacy.

Pleasant Hill (Shakertown), Kentucky — Shaker Heritage Restored

The Shakers built Pleasant Hill beginning in 1805, creating one of their most successful communities in the American West. At its peak, nearly 500 believers lived here, practicing their faith through communal living, celibacy, and dedication to craftsmanship. The community dissolved in 1910, but the buildings they constructed with such care have been meticulously preserved.

Thirty-four original Shaker buildings survive at Pleasant Hill, forming one of the nation’s most complete Shaker villages. The architecture reflects Shaker values—simple, functional, and beautifully proportioned. Clean lines, minimal decoration, and clever built-in storage demonstrate the Shaker principle that form follows function, an idea that influenced later design movements.

Walking through these whitewashed buildings provides insights into a fascinating American religious experiment. The Centre Family Dwelling, four stories tall, housed up to 100 Shakers, with separate staircases and doors for brothers and sisters who lived celibate lives. Meeting houses feature movable benches that could be pushed aside for the ecstatic dancing that gave Shakers their name.

Demonstrations of Shaker crafts reveal the exceptional quality that made their products famous. Furniture makers show techniques for creating the simple, elegant chairs and cabinets that collectors prize today. Gardens grow heirloom vegetables using Shaker methods, and interpreters explain the innovations—from the flat broom to the clothespin—that Shakers contributed to American life.

Jonesborough, Tennessee — Tennessee’s Oldest Town

Established in 1779, Jonesborough predates Tennessee statehood by seventeen years. The town served briefly as capital of the short-lived State of Franklin, a fascinating footnote in American history when settlers attempted to create the fourteenth state. That independent spirit still characterizes Jonesborough, which has preserved its historic character while cultivating unique cultural traditions.

Downtown Jonesborough’s historic buildings span two centuries of architectural evolution. The Chester Inn, built in the 1790s, hosted travelers including three presidents—Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, and Andrew Johnson. Brick commercial buildings from the 1800s line Main Street, their facades largely unchanged except for modern shop signs.

The Washington County Courthouse, built in 1913, dominates the town center with its Classical Revival architecture. But Jonesborough’s most distinctive tradition has nothing to do with buildings—it’s storytelling. The National Storytelling Festival, held annually since 1973, transformed this quiet town into America’s storytelling capital, attracting thousands of visitors who gather to hear traditional tales and contemporary narratives.

That emphasis on oral tradition feels appropriate for a town steeped in Appalachian heritage. The surrounding mountains preserved cultural traditions—music, crafts, and stories—that disappeared elsewhere. Walking Jonesborough’s historic streets while hearing tales told in the Southern mountain tradition creates powerful connections between place, history, and the living art of storytelling that has entertained humans since language began.