Long before highways and railroads crisscrossed the continent, America’s rivers served as the lifeblood of powerful Native civilizations. These waterways provided food, transportation, and trade routes that connected distant communities and built thriving economies.

The tribes who mastered these rivers didn’t just survive alongside them; they created sophisticated societies that shaped the landscape for thousands of years. From the mighty Mississippi to the winding Klamath, these Native nations turned rivers into highways of commerce, culture, and power.

Mississippian Culture (Cahokia) on the Mississippi River

Around 1100 CE, something extraordinary rose from the Mississippi River floodplains. Cahokia became North America’s largest pre-Columbian city, home to somewhere between 10,000 and 20,000 people at its peak.

That’s bigger than London was at the same time.

The city featured massive earthen mounds, some towering over 100 feet high, that served as platforms for temples and elite residences. Monks Mound, the largest structure, covered 14 acres at its base.

These weren’t just piles of dirt but carefully engineered monuments that required millions of basket-loads of earth.

Cahokia’s location on the Mississippi gave residents access to trade networks stretching from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico. Archaeologists have found seashells, copper, and exotic minerals that traveled hundreds of miles to reach this urban center.

The Mississippians controlled river commerce and transformed raw materials into finished goods that spread their influence across half a continent.

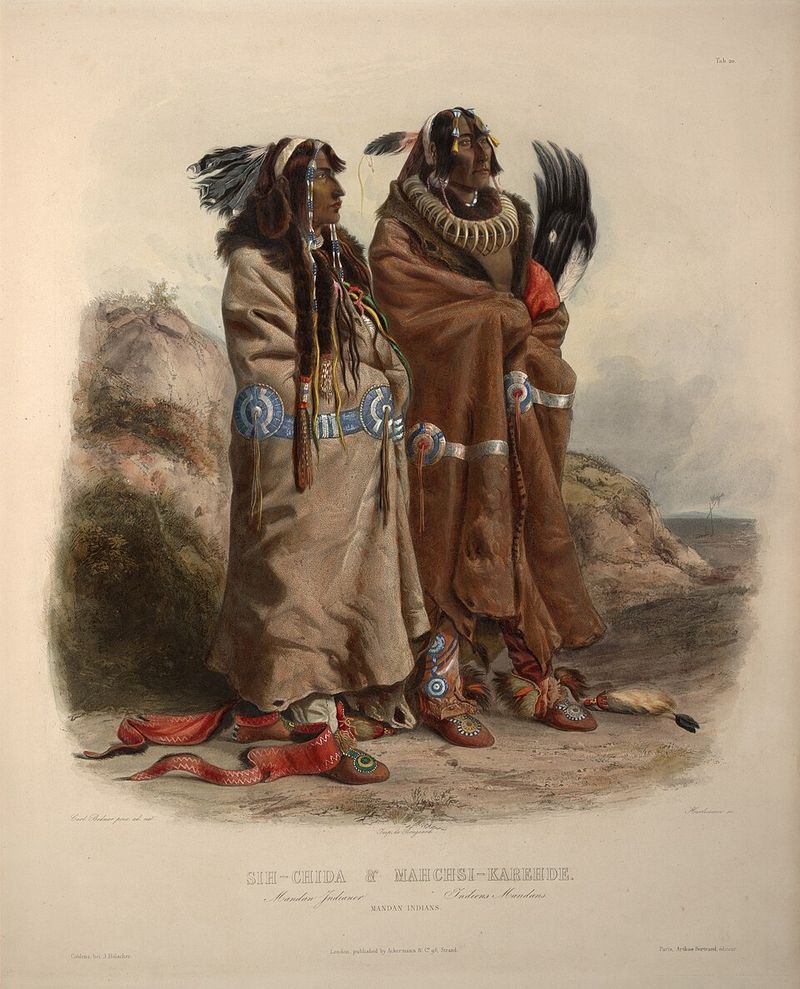

Mandan People on the Missouri River

The Mandan people built permanent villages along the Missouri River that became bustling trade centers where different worlds met. Plains nomads hunting buffalo would arrive with hides and meat, while Woodland tribes brought furs and crafted goods.

The Mandan sat right in the middle, brokering deals and taking their cut.

Their villages featured distinctive earth lodges that could house extended families through brutal prairie winters. These dome-shaped homes, covered with layers of willow branches and packed earth, stayed warm when temperatures plunged below zero.

Some lodges stretched 40 feet across and could accommodate 20 or more people comfortably.

Agriculture formed the backbone of Mandan prosperity. Women cultivated corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers in the rich river bottomlands, producing surpluses that supported both residents and visiting traders.

This reliable food supply meant the Mandan could maintain permanent settlements while neighboring tribes followed migrating buffalo herds, giving them enormous economic leverage.

Hidatsa Nation on the Missouri River

Hidatsa villages dominated key stretches of the Missouri River, and their underground storage technology gave them serious economic muscle. They dug bell-shaped cache pits deep into the earth, where cool temperatures preserved massive quantities of corn, squash, and dried meat.

These food reserves meant they could trade year-round, not just after harvest.

Long-distance commerce flowed through Hidatsa hands like water through the Missouri itself. Traders from hundreds of miles away knew they could count on Hidatsa merchants for reliable supplies and fair dealing.

The tribe developed a reputation for honesty that made their villages preferred stopping points along major trade routes.

Women held significant power in Hidatsa society, owning the crops, lodges, and storage pits. They made decisions about trade and distribution, giving Hidatsa communities a different dynamic than many neighboring tribes.

This system worked remarkably well, creating stable villages that lasted for generations in the same locations along the river’s productive floodplains.

Arikara Farmers on the Missouri River

When Lewis and Clark nearly starved during their famous expedition, guess who saved them? The Arikara people, whose agricultural expertise had been perfected over centuries along the Missouri River.

Their villages occupied such strategic positions that passing through Arikara territory without permission was basically impossible.

Corn was the Arikara’s secret weapon, but not just any corn. They developed advanced varieties adapted to the short growing season and unpredictable weather of the northern plains.

Some types could mature in just 60 days, while others resisted drought better than anything European settlers had seen. These weren’t lucky accidents but the result of careful selection over many generations.

The tribe’s fortified villages combined defense with commerce. High palisade walls protected residents and stored goods, while strategic locations allowed the Arikara to monitor river traffic and control access to prime hunting grounds.

European and American traders quickly learned that maintaining good relations with the Arikara wasn’t optional; it was essential for survival.

Natchez Nation on the Lower Mississippi River

The Natchez people built one of the most stratified societies in North America, ruled by a leader called the Great Sun who was treated like a living deity. When the Great Sun walked, his feet weren’t allowed to touch bare ground.

Servants carried him on a litter, and commoners had to bow and make specific sounds when he passed.

Their society divided into four distinct classes: Suns, Nobles, Honored People, and Stinkards (yes, that was the actual term). Strict marriage rules required higher classes to marry Stinkards, creating a complex social system that anthropologists still debate today.

This rigid hierarchy centered around massive earthen mounds where the elite lived and conducted ceremonies.

The lower Mississippi River provided the Natchez with abundant resources that supported this elaborate social structure. Rich soils produced surplus crops, while the river teemed with fish and attracted waterfowl.

French explorers were astonished by Natchez towns, with their planned layouts and monumental architecture that rivaled anything they’d seen in other Native territories.

Choctaw Nation on the Pearl and Tombigbee Rivers

Numbers tell a story, and for the Choctaw, those numbers were impressive. Before European contact, they maintained one of the largest populations in the entire Southeast, with estimates ranging from 15,000 to 20,000 people.

That kind of population density required serious organizational skills and abundant resources.

Rivers weren’t just boundaries for the Choctaw; they were highways connecting dozens of towns and villages. Dugout canoes carried people, goods, and messages along the Pearl and Tombigbee, creating a transportation network that held their nation together.

When you needed to travel 50 miles, walking through dense forests wasn’t your first choice. Paddling downstream was.

The Choctaw developed a sophisticated political system with three distinct geographical divisions, each with its own chiefs and councils. This distributed leadership meant no single leader could make decisions affecting the entire nation without consultation.

River travel made it possible for representatives from distant towns to gather for important meetings, maintaining unity across a large territory. Their diplomatic skills later proved crucial when dealing with European powers.

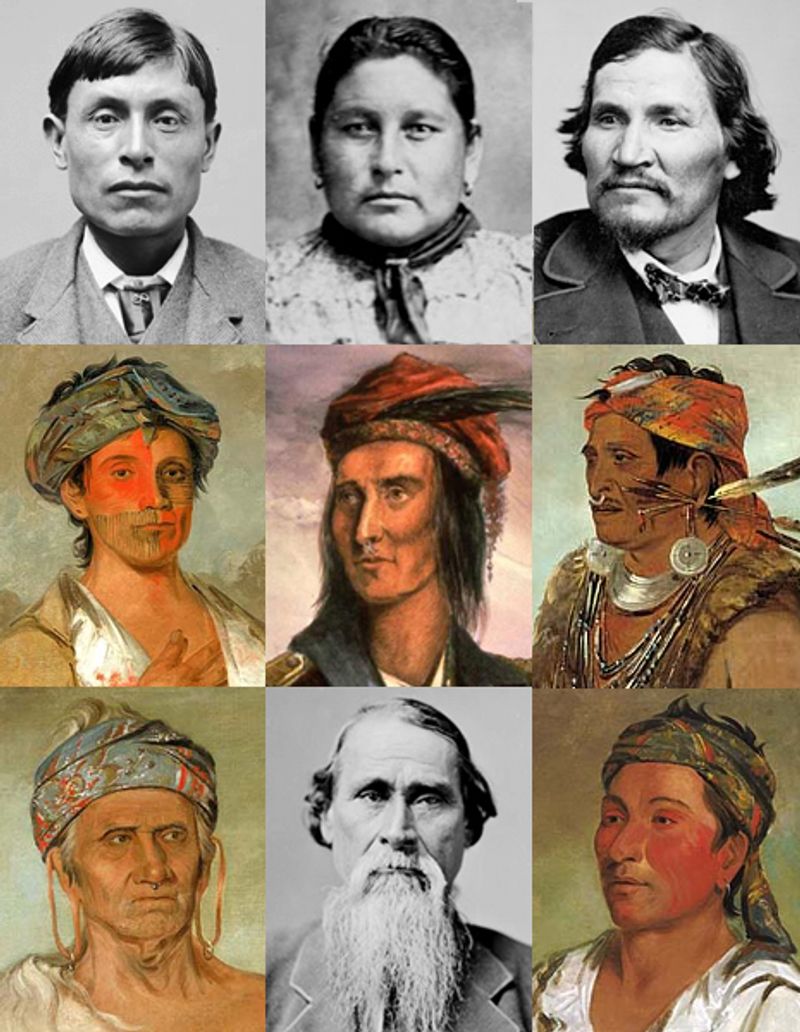

Chickasaw Warriors on the Tennessee River System

French colonial governors learned a hard lesson: don’t mess with the Chickasaw. Despite repeated attempts and superior numbers, French forces couldn’t break Chickasaw control of the Tennessee River system.

The tribe’s reputation as fierce warriors wasn’t just talk; it was backed by strategic brilliance and intimate knowledge of their territory.

River chokepoints became Chickasaw strongholds where they could monitor traffic and control access to vast hunting grounds. Their villages occupied high bluffs overlooking the water, giving defenders clear views of approaching enemies or traders.

These positions weren’t chosen randomly but represented generations of tactical thinking about how to dominate river corridors.

Trade and warfare intertwined in Chickasaw strategy. They maintained alliances with the British while resisting French expansion, playing European powers against each other to maintain independence.

This diplomatic maneuvering required constant communication across their territory, made possible by the river network that connected Chickasaw towns. Their success in preserving autonomy while neighbors fell to colonial pressure speaks to both their military prowess and political sophistication.

Osage People on the Osage and Missouri Rivers

When European traders arrived in Osage territory, they quickly discovered they weren’t calling the shots. The Osage controlled vast hunting territories that stretched across what’s now Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Arkansas.

If you wanted access to those prime beaver streams and buffalo ranges, you negotiated on Osage terms or you didn’t negotiate at all.

The tribe’s power came from strategic positioning at the intersection of different ecological zones. Prairie, woodland, and river systems all met in Osage country, creating incredible biodiversity and resource abundance.

They hunted buffalo on the plains, trapped beaver in streams, and cultivated crops in river bottomlands. This diversified economy made them less vulnerable to any single resource failure.

Osage political organization emphasized consensus and persuasion rather than coercion. Chiefs gained influence through generosity and wise counsel, not through inherited power alone.

This flexible system allowed the Osage to adapt quickly to changing circumstances, whether dealing with European traders, rival tribes, or American expansion. Their ability to maintain territorial control well into the 19th century demonstrated the effectiveness of their river-based strategy.

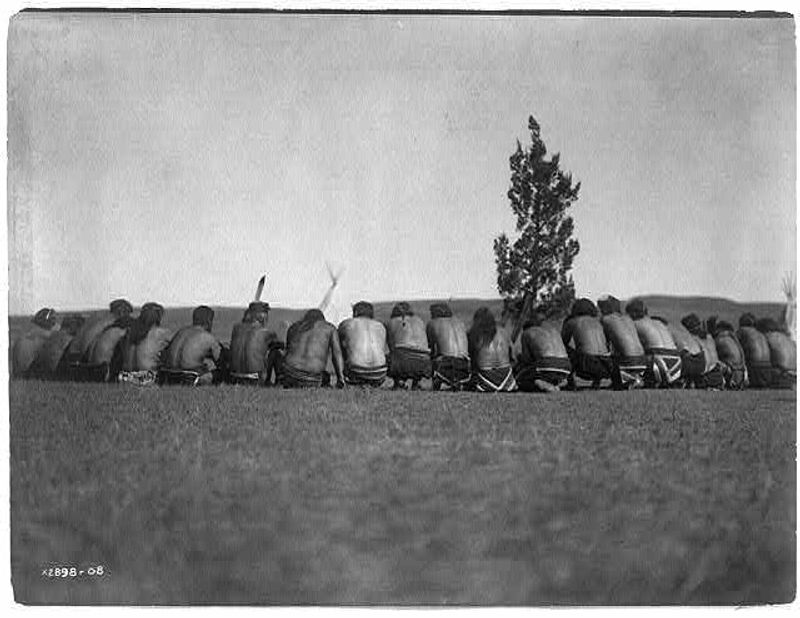

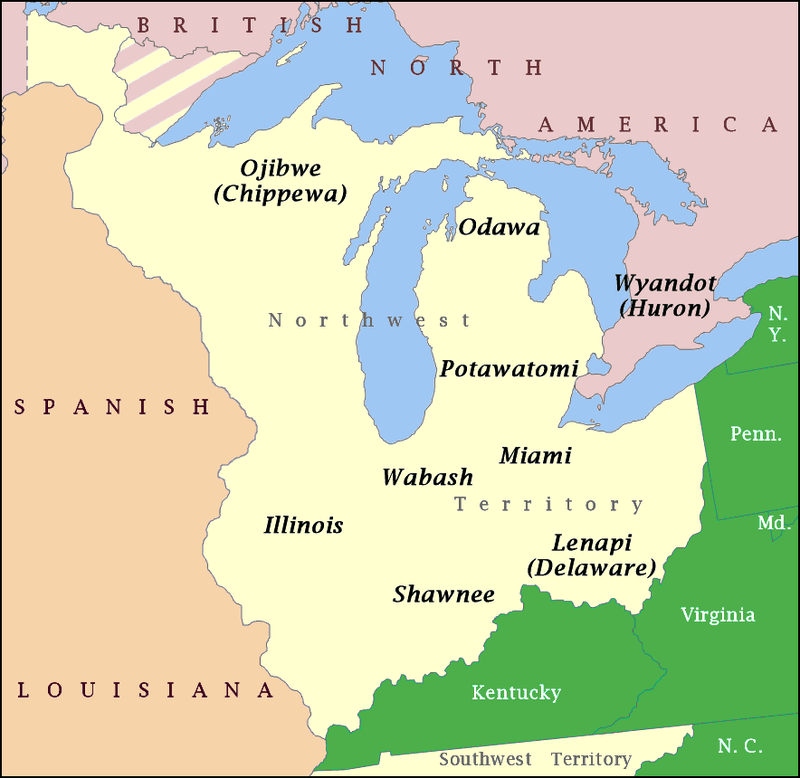

Illinois Confederation (Illiniwek) on the Illinois River

Unity brought strength to the Illinois Confederation, which joined multiple tribes into a single powerful alliance dominating the Illinois River. This wasn’t a loose association but a coordinated political and economic union that controlled trade flowing between the Great Lakes and Mississippi River systems.

Anyone moving goods north to south had to deal with the Illiniwek.

The Illinois River valley provided everything the confederation needed: rich agricultural land, abundant fish and waterfowl, and easy transportation. Villages dotted both banks, each contributing to the confederation’s collective strength.

When French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet descended the Illinois River in 1673, they found prosperous towns with large populations and ample food supplies.

Trade goods from across the continent passed through Illiniwek hands. Copper from Lake Superior, shells from the Gulf Coast, and furs from the northern forests all moved along routes the confederation controlled.

This middleman position generated wealth that supported a sophisticated culture with elaborate ceremonies, competitive games, and artistic traditions. The confederation’s power lasted until disease and warfare in the 1700s devastated their population.

Shawnee Nation on the Ohio River Valley

Mobility defined Shawnee culture in ways that confused European colonists who expected Native peoples to stay put. The Shawnee moved seasonally, annually, and sometimes permanently, using an extensive canoe network that connected communities across the Ohio River valley.

This wasn’t wandering; it was strategic flexibility that made them incredibly difficult to defeat or control.

Their canoe routes became communication highways that coordinated resistance against colonial expansion. When trouble erupted in one area, Shawnee messengers could quickly spread warnings and call for assistance from distant communities.

This network allowed them to organize multi-regional coalitions that fought coordinated campaigns against American expansion in the late 1700s.

The Ohio River valley’s resources supported this mobile lifestyle. Spring brought fish runs that could be harvested in massive quantities.

Summer meant tending crops in river bottomlands. Fall offered hunting opportunities as game moved toward winter ranges.

Winter camps occupied sheltered valleys with reliable firewood and water. By moving with the seasons, the Shawnee maximized resource access while minimizing environmental impact on any single location.

Miami Tribe on the Wabash and Maumee Rivers

Geography is destiny, and the Miami people held some of the most strategically valuable real estate in North America. Their territory included critical portage routes connecting the Great Lakes to the Mississippi watershed.

During high water, you could almost paddle from Lake Erie to the Wabash River with just short carries over land. The Miami controlled those carries.

These portages weren’t just convenient shortcuts; they were economic chokepoints worth fighting over. The Miami understood this perfectly and fortified key portage sites while maintaining diplomatic relations that allowed peaceful trade passage.

French, British, and later American officials all courted Miami favor because moving goods and troops through the region required Miami cooperation.

Villages along the Wabash and Maumee rivers served as trading posts where different cultures met and exchanged goods. The Miami acted as brokers, translators, and guides, earning profits from their geographic position.

This middleman role required sophisticated diplomatic skills, as the Miami had to balance relationships with multiple European powers, rival tribes, and their own confederation members. Their success in maintaining autonomy until the late 1700s showed remarkable political acumen.

Caddo Nation on the Red River

Engineering prowess set the Caddo apart from many neighboring tribes. They didn’t just settle along the Red River; they reshaped the landscape to suit their needs.

Permanent farming towns featured carefully planned layouts with central plazas, residential areas, and specialized work zones. But the really impressive part was their road system.

Caddo roads connected towns and aligned with river-based trade networks, creating an integrated transportation system that moved goods efficiently across their territory. These weren’t just deer trails widened by foot traffic but deliberately constructed paths that maintained consistent widths and cleared obstacles.

Some roads stretched for dozens of miles, requiring coordinated labor and maintenance.

Agriculture formed the economic foundation of Caddo prosperity. Rich Red River bottomlands produced abundant corn, beans, and squash, while hunting and gathering supplemented cultivated foods.

Surplus production supported a class of specialists including potters, who created distinctive ceramics that archaeologists find across the region. The Caddo weren’t just farmers; they were sophisticated urban planners who understood how infrastructure enabled economic growth and political power.

Wampanoag People on New England Rivers

Dense populations covered coastal New England long before the Mayflower arrived, sustained by Wampanoag mastery of riverine resources. They didn’t just fish; they engineered fish weirs that funneled migrating fish into traps, harvesting thousands of pounds during spring runs.

These stone and wooden structures showed sophisticated understanding of fish behavior and water flow.

Agriculture complemented fishing in the Wampanoag economy. Women cultivated the famous Three Sisters (corn, beans, and squash) in river valley soils enriched by annual floods.

They also grew tobacco, sunflowers, and other crops, creating diverse food sources that protected against single-crop failures. This agricultural productivity supported villages of several hundred people each.

When English colonists arrived in 1620, they encountered a Wampanoag confederacy led by Massasoit that controlled much of southeastern Massachusetts. The Wampanoag’s decision to assist the struggling Plymouth Colony wasn’t charity; it was strategic diplomacy aimed at gaining allies against rival tribes.

The rivers that sustained Wampanoag prosperity also became highways for cultural exchange and, ultimately, devastating epidemic diseases that killed up to 90 percent of the population before permanent English settlement.

Powhatan Confederacy on the James River

Over 30 tribes answered to Powhatan, the paramount chief whose confederacy dominated Virginia’s tidewater region when English colonists stumbled ashore at Jamestown. This wasn’t a loose alliance but a hierarchical political structure with Powhatan at the top, collecting tribute and commanding warriors from subordinate chiefs.

His power rested on control of the James River and its tributaries.

English survival depended entirely on Powhatan’s goodwill during Jamestown’s first desperate years. The colonists arrived at the wrong time of year, lacked farming skills, and chose a terrible location with brackish water and disease-carrying mosquitoes.

Without Powhatan-supplied corn, the English would have starved or abandoned the colony. Powhatan understood this leverage perfectly and used it to extract concessions and goods.

The James River wasn’t just a resource; it was a political tool. Powhatan controlled which English ships could travel upstream and where colonists could establish settlements.

His warriors could cut off river access, isolating Jamestown and preventing resupply. This strategic control gave the confederacy enormous bargaining power in early Anglo-Powhatan relations, though European diseases and relentless colonial expansion eventually overwhelmed Powhatan’s carefully constructed political system.

Yurok Nation on the Klamath River

Salmon wasn’t just food for the Yurok; it was the foundation of their entire worldview. Their economy, religion, social structure, and annual calendar all revolved around the salmon runs that surged up the Klamath River each year.

But here’s what made the Yurok remarkable: they managed this resource sustainably for centuries, maintaining abundant fish populations through careful stewardship.

Yurok fishing practices combined sophisticated technology with strict conservation rules. Weirs and nets harvested fish efficiently, but elders determined when fishing could begin and how much could be taken.

Certain stretches of river were off-limits during spawning season. First-salmon ceremonies honored the fish and reinforced cultural values about respecting nature’s cycles.

These weren’t just spiritual practices; they were effective resource management.

The Klamath River provided more than salmon. Yurok people harvested lamprey, sturgeon, and shellfish.

They gathered acorns in the surrounding hills and traded with inland tribes for obsidian and other goods. This diversified economy created wealth that supported one of the highest population densities in pre-contact California.

Yurok villages lined both banks of the lower Klamath, connected by canoes and shared cultural traditions centered on the river’s life-giving waters.