Some places fade away quietly, leaving behind only memories and old photographs. Others leave scars that run deeper than anyone could imagine.

In northeastern Oklahoma, one town didn’t just disappear because people moved away or industries closed down. This place became so contaminated that living there turned dangerous, and the government had to step in and relocate everyone.

Mountains of toxic waste still tower over empty streets where children once played. The ground itself hides deadly secrets that make this spot one of the most hazardous locations in America.

What happened here serves as a stark reminder of what can go wrong when profit matters more than people or the planet.

The Rise and Fall of a Mining Powerhouse

Picher sits at 36.9870116, -94.8307844 in Ottawa County, Oklahoma 74360, right in the heart of what used to be the Tri-State Mining District. For over a century, this town thrived as one of the biggest lead and zinc mining centers in the entire country.

Thousands of miners worked underground every day, pulling valuable ore from the earth. The town grew fast during its peak years, with businesses lining Main Street and families building homes near the mines.

Money flowed through Picher like water, and the population swelled to nearly 20,000 residents at one point. Schools, churches, and shops filled the streets with life and energy.

But nobody paid much attention to what all that mining was doing to the land and water. The focus stayed on production and profits while waste piled up around town.

By the 1970s, the mines started closing as the ore ran out. Workers left to find jobs elsewhere, and the population began shrinking.

What remained behind was far worse than an economic downturn. The environmental damage became impossible to ignore, setting the stage for one of America’s worst toxic disasters.

Chat Piles That Poisoned a Community

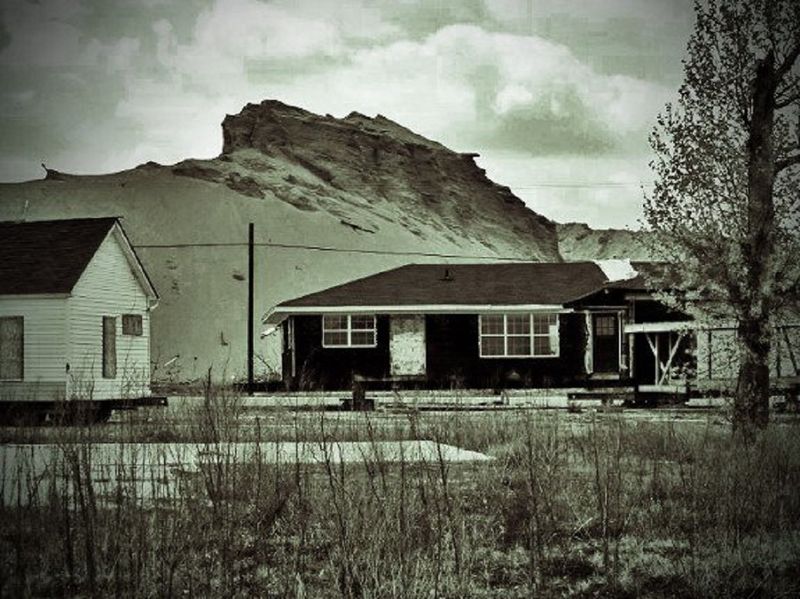

Drive through what’s left of Picher and you’ll see mountains that don’t belong in Oklahoma. These aren’t natural hills but massive piles of chat, the leftover rock and debris from mining operations.

Some of these waste heaps rise over 200 feet high and stretch across hundreds of acres. They dominate the landscape like monuments to industrial excess.

The chat contains dangerous levels of lead, zinc, cadmium, and other heavy metals. When wind blows across these piles, toxic dust spreads through the air and settles on everything nearby.

Rain washes contaminants into the soil and groundwater, creating an invisible web of poison. Children who grew up here often had lead levels in their blood that were dangerously high.

The Environmental Protection Agency designated Picher as one of the most contaminated sites in the nation. Testing showed that the soil around homes, schools, and playgrounds was loaded with toxins.

Even the dirt in yards where kids played contained lead concentrations far above safe limits. Families lived on top of this hazard for decades before anyone took action to protect them from the consequences.

Underground Dangers Lurking Below

The problems in Picher aren’t just on the surface. Beneath the streets and buildings lies a honeycomb of abandoned mine shafts and tunnels that crisscross under the entire town.

Miners dug out millions of tons of ore over the years, leaving vast empty spaces underground. These voids never got properly filled or stabilized after the mining stopped.

Ground subsidence became a serious threat as the tunnels started collapsing. Sinkholes opened up without warning, swallowing chunks of roads and property.

Houses developed cracks in their foundations as the earth shifted beneath them. Some buildings tilted at odd angles or partially collapsed into the ground.

Walking down certain streets felt risky because you never knew if the pavement might suddenly give way. The structural integrity of the entire town became questionable.

Engineers warned that more collapses were inevitable and that no amount of repair work could make the area truly safe again. The maze of tunnels extends so far that mapping them all proved nearly impossible.

This underground instability added another layer of danger to a place already contaminated above ground, making Picher doubly hazardous for anyone who stayed.

When the Government Said Leave

By 2006, federal officials could no longer ignore the crisis. The government offered to buy out residents and relocate them away from the contamination.

Most families accepted the offer because staying meant risking their health every single day. The buyout program gave people a chance to start over somewhere safer.

Watching neighbors pack up and leave must have felt surreal after generations of families had called this place home. One by one, houses emptied out and streets grew quieter.

The post office closed in 2009, and the town officially lost its incorporation in 2013. What had been a thriving community for over a century ceased to exist as a functioning municipality.

Some residents refused to leave despite the warnings and financial incentives. A handful of holdouts stayed in their homes, choosing familiar ground over the unknown.

But services gradually disappeared as the population dwindled to almost nothing. No stores, no schools, no emergency services remained to support those who stayed.

The evacuation transformed Picher from a contaminated town into an official ghost town, with only a few stubborn souls remaining among the ruins and the toxic legacy of its mining past.

The Tornado That Sealed Its Fate

Just when things seemed like they couldn’t get worse, nature delivered a final blow. On May 10, 2008, an EF4 tornado tore through Picher with winds exceeding 200 miles per hour.

The twister destroyed much of what remained standing in the already declining town. Buildings that had survived decades of mining damage couldn’t withstand the storm’s fury.

Debris scattered across the contaminated landscape, mixing with toxic dust and creating an even bigger mess. The disaster killed several people and injured many others.

Recovery efforts faced the challenge of cleaning up storm damage in a place already deemed too toxic to inhabit. Where do you even begin when everything is both destroyed and contaminated?

The tornado convinced many holdouts that staying was no longer worth the risk. It felt like a sign that Picher’s time had truly ended.

Emergency responders and cleanup crews had to wear protective equipment because of the lead dust stirred up by the storm. Even natural disasters became more dangerous here than in normal places.

This catastrophic event essentially sealed Picher’s fate as a ghost town, removing any lingering hope that the community might somehow recover or rebuild.

Exploring the Remnants Today

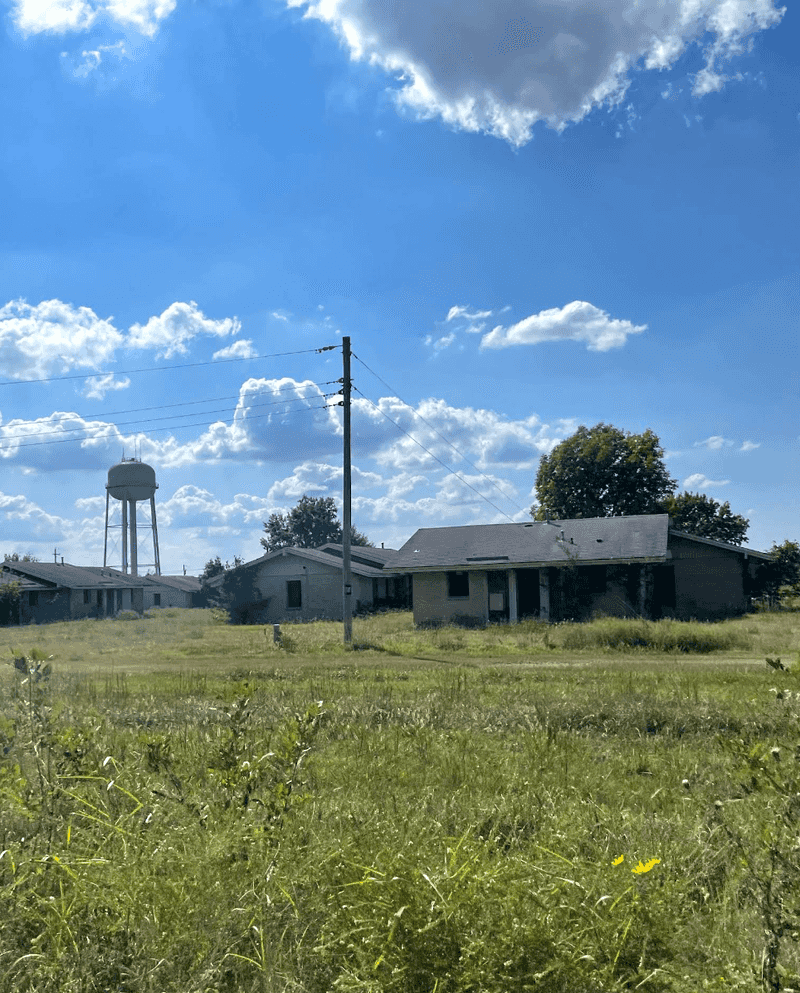

Visiting Picher today feels like stepping into a post-apocalyptic movie set. Empty buildings line streets where weeds push through cracked pavement and silence hangs heavy in the air.

You can still see the shells of old businesses, homes, and the high school, though most structures are deteriorating rapidly. Nature slowly reclaims what humans left behind.

Warning signs remind visitors about the contamination, though some urban explorers and curious travelers still come to witness this toxic ghost town firsthand. Photography enthusiasts find the decay hauntingly beautiful.

The chat piles remain as stark reminders of the mining era, their gray slopes visible for miles around. They’ll likely stand for centuries unless someone funds a massive cleanup effort.

Walking through Picher requires caution on multiple levels. The ground might collapse, buildings could fall apart, and toxic dust poses health risks with every breath.

Officials discourage people from visiting, but no fences or guards keep everyone out. Those who do explore should minimize their time there and avoid stirring up dust or touching contaminated surfaces.

What you witness here tells a powerful story about the long-term costs of environmental neglect and industrial greed.

The Ongoing Cleanup Challenge

Cleaning up Picher represents one of the most daunting environmental challenges in American history. The scope of contamination is so vast that complete restoration may never be possible.

The EPA has spent decades and millions of dollars on remediation efforts. Workers have removed contaminated soil from residential areas and attempted to stabilize some of the chat piles.

But the sheer volume of toxic material makes thorough cleanup extremely difficult and expensive. Every rainstorm potentially spreads more contamination into surrounding areas.

Groundwater remains polluted, and the underground mine system continues to pose risks. Some experts estimate that full remediation could take another century and cost billions more dollars.

The chat piles are so massive that moving them elsewhere isn’t practical. Instead, crews try to cap and vegetate them to prevent dust from spreading.

Nearby communities still worry about contamination affecting their water supplies and health. The toxic legacy of Picher extends beyond its borders into surrounding Oklahoma counties.

This ongoing struggle highlights how industrial pollution can create problems that outlast the industries themselves by generations, leaving taxpayers to foot the bill for cleanup efforts that may never fully succeed.

Lessons From a Toxic Legacy

Picher stands as a cautionary tale about the true cost of natural resource extraction. The wealth generated during the mining boom seems insignificant compared to the permanent damage left behind.

Thousands of families built their lives around an industry that ultimately poisoned their home. The jobs and prosperity came with a price that nobody fully understood until it was too late.

Environmental regulations were either non-existent or poorly enforced during Picher’s mining heyday. Companies focused on profits while ignoring the long-term consequences of their waste disposal practices.

The town’s story reminds us that economic development without environmental responsibility creates disasters that future generations must address. Short-term thinking leads to long-term catastrophes.

Children who grew up in Picher suffered health problems that will affect them for life. Some developed learning disabilities, behavioral issues, and other conditions linked to lead exposure.

Today, Picher serves as a stark example in environmental science courses and policy discussions. What happened there helps shape better regulations and mining practices elsewhere.

The abandoned town stands as a monument to human shortsightedness, a place where the land itself became so toxic that people had no choice but to walk away forever.