Deep in the jungles of Vietnam lies a cavern so massive and otherworldly that visitors often feel they’ve stepped onto another planet. Son Doong Cave, discovered less than two decades ago, holds the title of Earth’s largest cave passage, and its scale defies imagination.

From underground rivers to its own jungle ecosystem complete with towering trees, this natural wonder challenges everything we thought we knew about what exists beneath our feet.

1. It’s the world’s largest cave passage by volume – by a lot

When scientists measure caves, they look at volume, not just length. Son Doong absolutely crushes the competition with a measured volume of approximately 38.5 million cubic meters.

That’s not a typo or an exaggeration.

To put this in perspective, the second-largest cave passages on Earth don’t even come close to matching these numbers. Son Doong’s volume is so extraordinary that it redefined what geologists thought was possible for natural cave formation.

The sheer amount of space hollowed out by water over millions of years is mind-boggling.

What makes this even more remarkable is that Son Doong wasn’t formed by some unique geological event. It’s simply the result of ordinary water erosion happening on an extraordinary scale over an extremely long period.

The limestone bedrock in this region of Vietnam proved perfect for this massive excavation.

Standing inside Son Doong, the volume becomes visceral rather than abstract. The darkness swallows flashlight beams.

Sounds echo for seconds. The air feels different when there’s that much space around you.

This isn’t just the world’s largest cave by volume; it’s a completely different category of underground space.

2. The dimensions are so extreme they sound made up (but they’re real)

200 meters tall and 150 meters wide. Stretch that for about 9 kilometers.

Those are the dimensions of Son Doong’s main passage, and they sound like someone made an error with the decimal point.

A 200-meter ceiling is taller than a 60-story skyscraper. The width of 150 meters is wider than a regulation soccer field.

And this isn’t just a single chamber; these proportions continue for kilometers through the mountain.

Surveyors who first mapped Son Doong had to triple-check their measurements because the numbers seemed impossible. Traditional cave surveying equipment barely worked at this scale.

They needed specialized laser distance meters typically used for large outdoor projects, not underground exploration.

The psychological impact of these dimensions is profound. Human brains aren’t wired to process spaces this large underground.

Our instincts tell us we should see sky, not rock, at such distances. Visitors frequently report feeling disoriented or experiencing vertigo, not from height, but from the sheer wrongness of so much space existing beneath a mountain.

These dimensions push the boundaries of what feels real.

3. Its ‘average passage size’ is bigger than many famous caves’ main chambers

Here’s where things get truly absurd: Son Doong’s average passage size is approximately 67.2 meters. Not its maximum height or widest point, but its average throughout the entire length.

Most famous show caves around the world would consider a 67-meter chamber their crown jewel.

Mammoth Cave in Kentucky, Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico, and countless other celebrated caves have spectacular rooms that tourists flock to see. Many of these showcase chambers don’t reach 67 meters in any dimension.

Son Doong maintains that as its baseline throughout.

This average is why photographs of Son Doong look fake even when they include people for scale. A tiny human figure at the bottom of a 67-meter average passage simply doesn’t compute visually.

Our brains keep trying to reinterpret the image as something smaller with the person closer to the camera.

The consistency of these dimensions is geologically fascinating. It suggests incredibly uniform erosion conditions over millions of years.

The underground river that carved Son Doong must have maintained relatively stable flow rates and pathways for an enormous span of time, something quite rare in cave formation.

4. People compare it to fitting a Manhattan/NYC block inside

Travel writers love hyperbole, but the comparison to fitting a New York City block with 40-story buildings inside Son Doong isn’t marketing hype. It’s actually a reasonable way to help people grasp the scale.

A typical Manhattan block is roughly 80 meters wide and 270 meters long.

Son Doong’s dimensions easily accommodate this. The 150-meter width provides ample clearance, the 200-meter height exceeds the roughly 120-140 meters of a 40-story building, and the 9-kilometer length means you could fit dozens of blocks end to end.

The volume calculation backs this up completely.

What makes this comparison particularly effective is that most people have seen pictures of New York or visited a major city. We have a mental reference for what a city block with tall buildings looks like.

Transplanting that familiar image into an underground setting creates the cognitive dissonance that helps people understand why Son Doong feels alien.

Geologists initially resisted these dramatic comparisons, preferring dry technical measurements. But they’ve come to accept that sometimes you need a skyscraper-in-a-cave mental image to convey what millions of cubic meters actually means in human terms.

5. It’s home to some of the tallest stalagmites ever recorded

Growing from the cave floor like ancient stone trees, Son Doong’s stalagmites reach heights of up to 80 meters. These formations are among the tallest known anywhere on Earth, and they took millions of years to grow at rates measured in millimeters per century.

Stalagmites form from mineral-rich water dripping from the ceiling. Each drop leaves behind a tiny deposit of calcite.

Over geological timescales, these deposits accumulate into the towering columns we see today. An 80-meter stalagmite represents an almost incomprehensible span of continuous, undisturbed growth.

What’s remarkable about Son Doong’s giants is their structural integrity. At 80 meters, these formations are approaching the theoretical limits of what calcite can support under its own weight.

They’re engineering marvels created entirely by natural processes, with no blueprint or planning, just physics and chemistry working over eons.

Walking among these formations feels like wandering through a petrified alien forest. They’re not uniform pillars but organic shapes, bulging and tapering in response to changing water flow patterns over millennia.

Some are thick as tree trunks; others are slender and seemingly fragile despite their massive height. They’re proof that nature’s patience produces wonders no human construction can match.

6. It has its own underground ‘jungle’ (with real trees)

Sunlight streaming through massive holes in the cave ceiling has created something botanists never expected to find underground: actual jungle ecosystems thriving hundreds of meters beneath the mountain surface. These aren’t mosses or fungi adapted to darkness; they’re full-sized trees, vines, and undergrowth.

Two enormous dolines (ceiling collapses) act as natural skylights, pouring in enough light to support photosynthesis. Rain falls through these openings, providing water.

Seeds blown in by wind or carried by birds germinate in the soil that has accumulated on the cave floor over millennia. The result is pockets of forest that exist in a twilight world between surface and subterranean.

The biological implications are fascinating. These isolated ecosystems have limited gene flow from the outside world.

Scientists are studying whether the plants show any adaptations to the unusual light conditions, higher humidity, and stable temperatures found inside the cave. Early research suggests some interesting variations in leaf structure and growth patterns.

For visitors, stumbling into these jungle sections feels surreal. After hours of walking through barren rock passages, suddenly encountering living trees creates a profound sense of cognitive dissonance.

It’s beautiful, unexpected, and slightly unsettling all at once.

7. Rivers run through it so it’s not just rock, it’s moving landscape

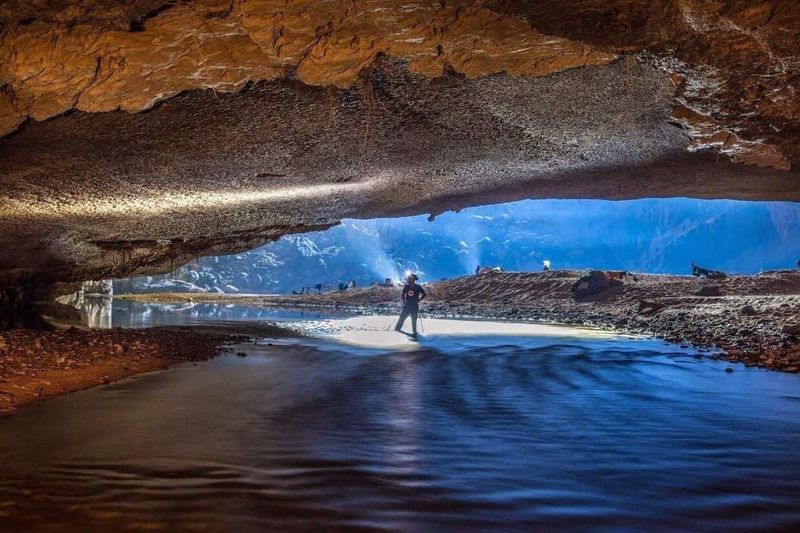

A powerful underground river system courses through Son Doong, and this isn’t a gentle stream. We’re talking about a fast-flowing waterway that continues the excavation work that created the cave in the first place.

The sound of rushing water echoes through the passages, a constant reminder that this landscape is still actively forming.

The river’s presence transforms Son Doong from a static geological feature into a dynamic, living system. Water levels fluctuate with seasonal rainfall, sometimes rising dramatically and making passages impassable.

Mist hangs in the air, creating atmospheric effects that photographers dream about. Moisture constantly works on the limestone, slowly but steadily reshaping the cave.

This moving water is also why Son Doong exists at all. Over millions of years, slightly acidic water dissolved the limestone bedrock, gradually enlarging what started as small fractures into the massive passages we see today.

The process continues; Son Doong is still growing, though at geological speeds imperceptible to human observation.

For expedition teams, the river presents both challenges and opportunities. It’s a source of fresh water and a natural pathway through the cave.

But it’s also dangerous during high flow periods, capable of sweeping away equipment or blocking routes. Respecting the river’s power is essential for anyone venturing into Son Doong.

8. ‘Son Doong’ is tied to water and the name hints at what built it

The name Son Doong translates roughly to “mountain river cave,” and this isn’t poetic license. It’s a straightforward description of what the cave fundamentally is: a passage carved by a river through a mountain.

The Vietnamese name captures the cave’s essential nature in three simple words.

Local knowledge often preserves geological truth in surprisingly accurate ways. The people living near Son Doong for generations understood that water was the defining feature of this system, even without modern scientific equipment.

They heard the river, saw water emerging from the mountain, and named it accordingly.

This connection between name and formation process is important for understanding why Son Doong became so large. Rivers are the most powerful cave-carving force in nature.

Unlike caves formed primarily by slow seepage, river caves can excavate enormous volumes of rock relatively quickly (in geological terms). The sustained flow of a major river over millions of years explains Son Doong’s extraordinary dimensions.

The name also serves as a reminder that this isn’t a static museum piece. Son Doong remains fundamentally what it has always been: a mountain river cave.

The water that gave it its name continues to flow, continues to shape the passages, and continues to make Son Doong a living geological system rather than a relic of the past.

9. The discovery story is surprisingly recent (and very human)

A local farmer named Hồ Khanh stumbled upon Son Doong’s entrance around 1990 or 1991 while seeking shelter from a storm in the jungle. He heard the roar of water and wind coming from a hole in the mountainside but didn’t venture inside.

The entrance was noted, then essentially forgotten for nearly two decades.

This is not a tale of ancient discovery or colonial-era exploration. Son Doong remained unknown to science until the 21st century.

Hồ Khanh couldn’t relocate the entrance for years; the jungle is dense, and one hole in a mountainside looks much like another when you’re not specifically searching.

In 2009, a British-Vietnamese expedition team finally entered Son Doong properly, with Hồ Khanh serving as guide after relocating the entrance. What they found exceeded all expectations.

The surveying and mapping that followed confirmed what initially seemed impossible: this was the largest cave passage on Earth.

The recent discovery date is humbling. We like to think we’ve explored every corner of our planet, but Son Doong proves that massive natural wonders can still hide in plain sight.

It took the right combination of local knowledge, international expertise, and sheer determination to reveal this underground world to science and the public.

10. Public visits only became possible in 2013 under strict control

Scientific expeditions explored and surveyed Son Doong starting in 2009, but it took four more years before the first paying visitors could enter. In 2013, carefully controlled expedition-style tourism began, opening this natural wonder to a select few who could meet the physical and financial requirements.

The delay between discovery and public access was deliberate. Authorities and conservationists needed time to assess the cave’s fragility, establish safe routes, and create management protocols that would protect Son Doong while allowing limited access.

This wasn’t going to be a typical tourist cave with paved paths and electric lights.

The decision to allow any public access at all was controversial. Some scientists argued that Son Doong should remain closed to preserve it in pristine condition.

Others countered that allowing limited, controlled visits would build public support for conservation and provide economic incentives for protection. The compromise was strict limitations and high standards for visitors.

Opening Son Doong in 2013 created a new category of adventure tourism. This wasn’t sightseeing; it was legitimate expedition caving made accessible to fit civilians willing to push their limits.

The timing also coincided with social media’s rise, which meant stunning images of Son Doong could reach global audiences almost instantly, raising awareness of this natural wonder.

11. It’s not a casual stroll – it’s an expedition into a living natural wonder

Visiting Son Doong requires a multi-day expedition (typically four to five days), professional guides, specialized equipment, and physical fitness. You’ll camp inside the cave, cross the underground river multiple times, climb challenging terrain, and navigate in complete darkness.

This is not a theme park experience.

The logistics are complex and expensive. Permits must be obtained, guide companies must be licensed and experienced, safety equipment must meet strict standards, and participants must demonstrate adequate fitness levels.

The cost runs into thousands of dollars per person, reflecting the expertise and support required.

Physical challenges are real and varied. River crossings can involve chest-deep water.

Some passages require scrambling over boulder fields. The humidity is intense, and temperatures fluctuate.

Participants carry their own gear for significant distances. People have turned back after realizing the difficulty exceeded their expectations.

But the rewards match the challenges. Sleeping in an underground jungle, watching light filter through dolines, standing in passages that could swallow skyscrapers—these experiences are genuinely transformative.

Son Doong isn’t fragile because it’s delicate; it’s fragile because it’s irreplaceable. The demanding access requirements ensure that only those who truly appreciate what they’re seeing, and who will follow strict leave-no-trace protocols, ever set foot in this alien world beneath Vietnam’s mountains.