Hidden deep in the rugged San Bois Mountains of southeastern Oklahoma lies a place where the natural world and frontier legend have long intertwined. Today a beloved state park, this historic hideout once served as a remote refuge for deserters, fugitives, and some of the Wild West’s most notorious outlaws.

The towering sandstone bluffs, winding forests, and deep clefts in the rock created a landscape that was almost tailor-made for those seeking to vanish from the reach of the law. I had the chance to explore this incredible place firsthand, and walking those same trails where outlaws once roamed felt like stepping straight into a history book.

Every corner of this park whispers stories of frontier justice, daring escapes, and the rugged characters who made this wilderness their sanctuary.

A Historic Hideout Tucked in the San Bois Mountains

Robbers Cave State Park sits at 2084 NW 146th Rd, Wilburton, OK 74578, in the heart of the San Bois Mountains. When I first arrived, the sheer remoteness of the location struck me immediately.

This wasn’t just another state park with manicured lawns and easy access. The landscape felt wild, almost untamed, with dense forests of oak, pine, and cedar stretching in every direction.

The park covers more than 8,000 acres of rugged terrain, and the centerpiece is the famous cave itself—a series of sandstone crevices, ledges, and hidden recesses carved into towering bluffs. As I hiked closer, I could see why outlaws chose this spot.

The natural rock formations provided perfect cover, with multiple escape routes and vantage points to spot approaching lawmen.

Oklahoma’s frontier history is rich and complex, and this park preserves one of its most colorful chapters. The cave isn’t a single cavern but a network of hiding spots that blend seamlessly into the surrounding wilderness.

Standing there, I could almost hear the echoes of hoofbeats and whispered plans. The park is open year-round, with hours varying by season, and I recommend visiting early in the morning to experience the same quiet solitude the outlaws must have cherished.

Ancient Roots Before the Outlaws Arrived

Before gunslingers and bandits made these hills infamous, the land had been home to indigenous peoples for centuries. Archaeological evidence links the area to the Spiro Mounds culture, a sophisticated society of builders and traders connected to the broader Mississippian world.

Walking the trails, I tried to imagine these early inhabitants moving through the same forests, hunting game and gathering near the streams.

By the 17th century, Osage and Caddoan tribes frequented the region, drawn by abundant bison and rich hunting grounds. French trappers later explored these woods, leaving behind names like Sans Bois and Fourche Maline—linguistic fingerprints of early European contact.

The layers of history here run deep, far beyond the outlaw tales that dominate popular imagination.

What struck me most was how the landscape itself shaped human activity across generations. The same features that protected ancient hunters—dense cover, fresh water, elevated vantage points—later made this place ideal for those fleeing the law.

The park offers interpretive programs that touch on this deeper history, helping visitors appreciate the full timeline. I found these stories just as compelling as the Wild West legends, adding context to the land’s enduring appeal as a refuge.

Indian Territory and Lawless Frontier Days

After the Civil War, this region became part of Indian Territory, a vast expanse where displaced tribes lived amid frontier uncertainty and minimal law enforcement. The federal government’s light touch here created a power vacuum that outlaws quickly exploited.

I learned that marshals from Fort Smith, Arkansas, had jurisdiction but faced enormous challenges covering such a massive, rugged territory.

The cave’s physical structure made it nearly perfect for hiding. It’s not a deep underground cavern but rather a series of crevices and high ledges set into sandstone bluffs.

Multiple entry points offered escape routes known only to those familiar with the terrain. The surrounding woods made tracking difficult, and the remote location meant posses often arrived too late.

Standing at one of the higher ledges, I could see for miles across the forested hills. Any approaching riders would be visible long before they reached the cave.

The strategic advantage was obvious. Outlaws could rest, tend their horses, and plan their next moves with relative security.

The lack of formal law enforcement in Oklahoma’s Indian Territory made places like this invaluable to those living outside the law, and the landscape itself became an accomplice to countless frontier crimes.

Jesse James and the James-Younger Gang

No outlaw legend looms larger over this place than Jesse James. The former Confederate guerrilla turned bank and train robber became one of America’s most famous criminals, and local tradition firmly links him to the cave.

While direct documentation is scarce, the James-Younger Gang’s known movements through the region make the connection plausible. They needed places exactly like this—remote, defensible, and far from federal authority.

The gang’s robberies across the Midwest generated intense pursuit, pushing them deeper into sparsely populated territories. Indian Territory offered the perfect refuge between jobs.

I found myself wondering which ledge Jesse might have used as a lookout, or where the gang tethered their horses in the trees below. The park doesn’t make definitive claims, but the interpretive materials acknowledge the strong oral history connecting James to the site.

What makes these legends endure is their grounding in reality. The James-Younger Gang did operate in this region, and they did need hideouts.

Whether Jesse James personally camped in this exact cave may never be proven, but the broader pattern of outlaw activity here is well established. Walking through the narrow passages, I felt the weight of that history—real or embellished—pressing close around me.

Belle Starr, the Bandit Queen

Belle Starr remains one of the most fascinating figures in Wild West lore, and her connection to this area is particularly strong. Known for horse theft, bootlegging, and associations with various outlaws, Starr lived in a cabin not far from the cave.

Local tradition holds that she welcomed fugitives passing through these woods, possibly even guiding them to concealment spots.

What drew me to Starr’s story was her defiance of conventional gender roles in the frontier era. She rode hard, carried weapons, and commanded respect in a male-dominated criminal underworld.

Historical records confirm her presence in the region and her connections to known outlaws, even if some details have been romanticized over time. The park’s exhibits include information about her life, separating verified facts from legend.

Starr’s eventual fate came not far from here, but her legacy as the Bandit Queen endures. I found it striking how her story intertwines with the cave’s reputation—both represent the untamed spirit of Oklahoma’s frontier days.

Whether she personally used the cave or simply operated in its orbit, her presence in the area’s history adds another layer to the outlaw mythology. The wilderness that sheltered her and others like her remains largely unchanged, still wild and still whispering its secrets.

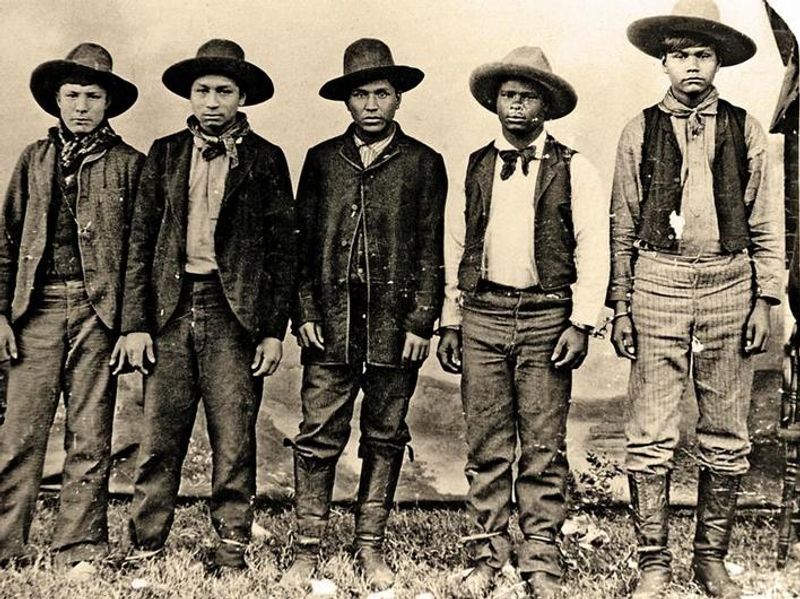

Other Notorious Fugitives and Gangs

Beyond Jesse James and Belle Starr, numerous other outlaws allegedly used these hills as refuge. The Younger Gang, the Daltons, and the Rufus Buck Gang all appear in historical accounts connected to the region.

Indian Territory’s informal governance made it a natural crossroads for drifting bands of criminals looking to resupply, rest, or wait out pursuit.

The Dalton Gang, known for their audacious bank and train robberies, operated extensively in Oklahoma Territory during the 1890s. The Rufus Buck Gang, though active for only a brief period, became infamous for their violent crime spree.

While direct evidence linking specific gangs to this exact cave is limited, the broader pattern of outlaw activity in the San Bois Mountains is well documented.

As I explored the various crevices and ledges, I thought about how many different fugitives might have sheltered here over the years. Each gang had its own story, its own desperate reasons for seeking refuge in this wilderness.

The cave became a kind of neutral ground, a place where the law couldn’t easily reach. Oral history passed down through generations helps fuel these legends, and even where fact blurs into folklore, the underlying truth remains: this was genuinely outlaw country, and the cave served its purpose well.

The Harsh Reality of Life on the Run

Romantic legends aside, life for outlaws hiding in the cave was brutal and uncertain. There were no comforts—just rocky ledges, exposure to the elements, and constant vigilance.

I tried to imagine spending days or weeks here, sleeping on stone, rationing supplies, and keeping watch for posses. The reality must have been exhausting and nerve-wracking.

Outlaws had to hunt or forage for food, tend their horses hidden among the trees, and maintain their weapons and gear. The thick cover of oak, pine, and cedar that provided concealment could quickly become a prison if weather turned bad or supplies ran low.

Water sources were nearby but required careful trips down from the bluffs. Every sound—a snapping twig, distant voices—could signal danger.

Legends persist about buried loot somewhere near the cave or along its trails. No verified treasure has ever been found, but the possibility adds mystery for modern visitors.

I found myself scanning the ground and rock faces, half-joking with other hikers about hidden gold. The truth is that most outlaws probably spent their stolen money quickly, and any caches left behind have long since been claimed by time and nature.

Still, the stories endure, adding one more layer to the cave’s enduring mystique.

Transformation from Outlaw Den to State Park

The cave’s transformation into public land is a remarkable story of redemption and vision. In 1929, Carlton Weaver, a Wilburton newspaper editor and politician, donated 120 acres near the cave to the Boy Scouts of America as a campsite called Camp Tom Hale.

Skilled inmates from the Oklahoma State Penitentiary helped construct early facilities using local stone—a fitting irony given the site’s outlaw past.

During the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps arrived as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs.

The CCC built roads, bathhouses, trails, cabins, group camps, and recreation shelters that formed the backbone of Oklahoma’s early state park system. I noticed their craftsmanship throughout the park—sturdy stone structures that have weathered decades with grace.

In 1936, the park was officially renamed Robbers Cave State Park in recognition of its colorful heritage. It later became one of the state’s most popular outdoor destinations.

Today the park encompasses more than 8,000 acres and includes Lake Carlton, Lake Wayne Wallace, and Coon Creek Lake. The transformation from outlaw refuge to family-friendly recreation area represents Oklahoma’s own journey from frontier territory to modern statehood, and walking these trails felt like witnessing that evolution firsthand.

Modern Recreation and Natural Beauty

Today’s park offers an impressive array of outdoor activities that would astonish its former outlaw residents. I spent time exploring the extensive trail system, which winds through forests and along ridgelines with spectacular views.

The park is particularly popular for rock climbing and rappelling, with the same sandstone bluffs that once sheltered fugitives now challenging modern adventurers.

The three lakes—Lake Carlton, Lake Wayne Wallace, and Coon Creek Lake—provide excellent fishing opportunities. I watched families trying their luck at trout fishing, a far cry from the furtive camps of Jesse James’s era.

Horseback riding trails let visitors experience the landscape much as the outlaws did, though with considerably more comfort and legality. The park also offers cabins, campgrounds, and a nature center with educational programs.

What impressed me most was how the park balances recreation with historical preservation. Interpretive signs along the trails explain the outlaw history without glorifying criminal activity, while the natural beauty speaks for itself.

The rugged terrain that once made this place ideal for hiding now makes it perfect for hiking, photography, and simply escaping modern life. Oklahoma has successfully transformed a symbol of lawlessness into a destination celebrating both natural heritage and frontier history.

Living History and Enduring Legacy

My visit to Robbers Cave left me with a profound appreciation for how places can evolve while retaining their essential character. The same trails that might have echoed with outlaw boots now welcome thousands of visitors annually, all drawn by the combination of natural beauty and frontier mystique.

The park’s interpretive programs help connect past and present, even as the interplay of myth and reality continues to fascinate history enthusiasts.

Whether Jesse James actually camped in this specific cave may never be definitively proven, but the broader truth remains undeniable: this was genuine outlaw country, and these hills sheltered desperate men and women fleeing frontier justice. The landscape hasn’t changed much—it’s still rugged, still remote, still capable of keeping secrets.

That continuity creates a tangible connection to the past that few places can match.

As I watched the sunset over Lake Carlton, painting the San Bois Mountains in shades of gold and crimson, I understood why this place captivates visitors. It represents the raw, wild spirit of Oklahoma’s frontier days—untamed, dangerous, and utterly unforgettable.

The outlaws are long gone, but their legacy lives on in every shadowed crevice and windswept bluff, reminding us of a time when the West was still being won and lost in places exactly like this.