Have you ever looked at a flight map and wondered why planes seem to take strange, curved paths over the Pacific Ocean instead of flying in a straight line? Many people think airlines are avoiding the Pacific, but the truth is much more interesting.

The real reasons involve science, safety, and smart planning that might completely change how you think about air travel.

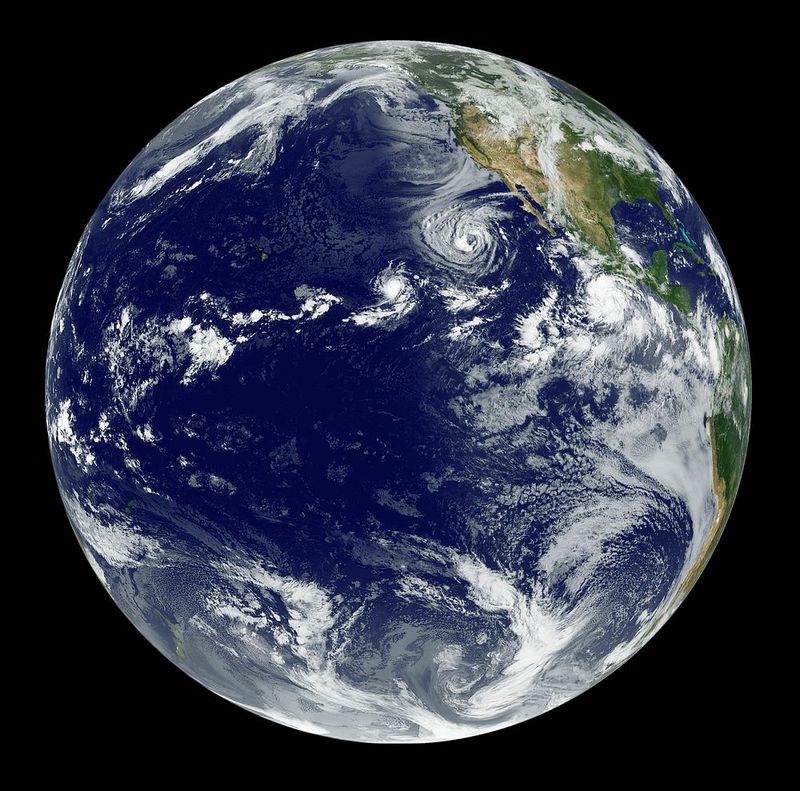

1. A Straight Line on a Flat Map Is Often Not the Shortest Path

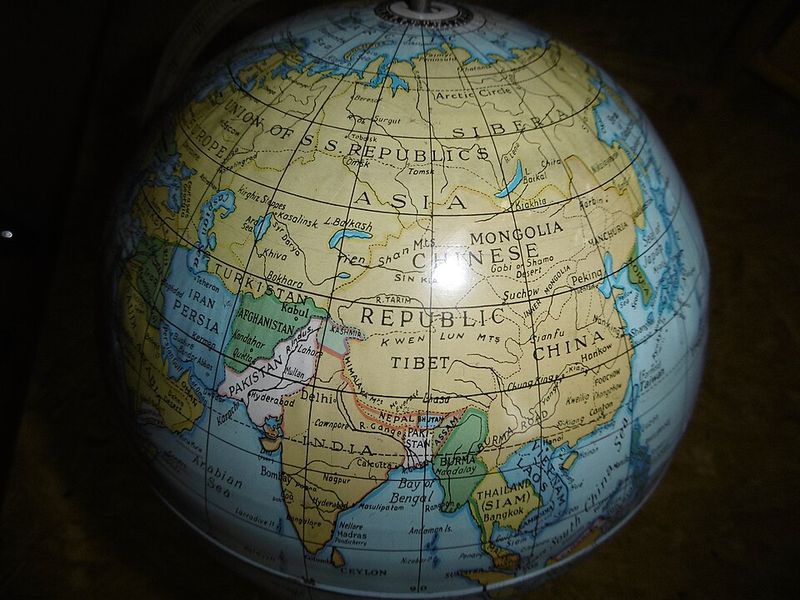

The shortest distance is not what you might expect from looking at a flat piece of paper. Our planet is a sphere, and the shortest path between two points on a sphere is called a great-circle route.

When cartographers make maps, they have to flatten Earth onto paper, which distorts distances and shapes. This is why Greenland looks huge on many maps even though it is much smaller than Africa in reality.

The same distortion affects how we see flight paths.

On a common map projection like the Mercator, great-circle routes appear curved and longer than they actually are. What looks like a straight line across the Pacific on your map is often a much longer journey in real miles.

Pilots and dispatchers use special tools and calculations to find the true shortest distance.

Airlines save fuel, time, and money by following these curved paths. Next time you see a flight tracker, remember that the curve you see is actually the most efficient route, not a detour at all.

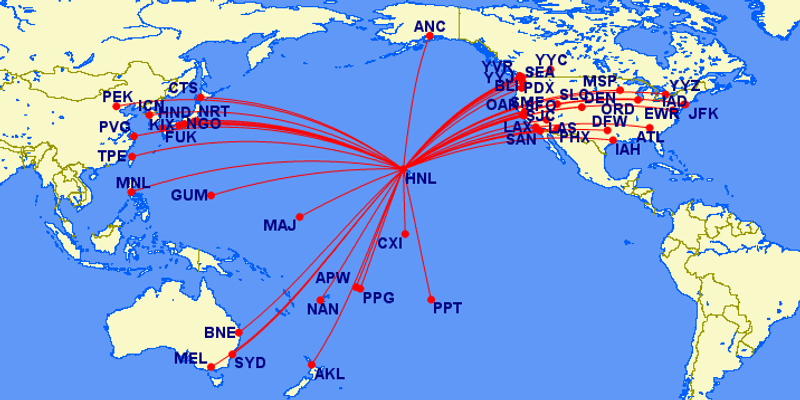

2. Great-Circle Routes Between Asia and North America Naturally Drift North

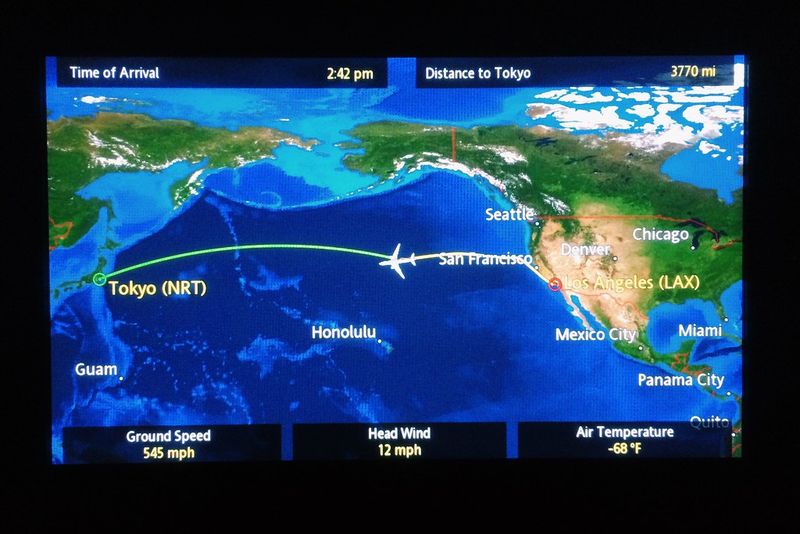

When you look at the line from Tokyo to Los Angeles, you trace the true shortest path on a globe, but you will notice something surprising: the route arcs way up north, sometimes passing close to Alaska or the Aleutian Islands. This is not a mistake or a detour.

Because Earth is round, the shortest distance between two points at similar latitudes often passes through higher latitudes. For flights connecting cities in Japan, South Korea, or China with destinations in the United States or Canada, the most efficient route naturally swings northward.

What seems like going out of the way is actually saving hundreds of miles.

This northern arc also has practical benefits beyond just distance. Flying closer to land means more diversion airports are available if something unexpected happens.

Pilots appreciate having options, and passengers benefit from safer, faster journeys.

Airlines use sophisticated flight planning software that calculates these routes down to the nautical mile. The next time you fly across the Pacific, check your flight path on the seat-back screen and watch how it curves gracefully northward instead of cutting straight across.

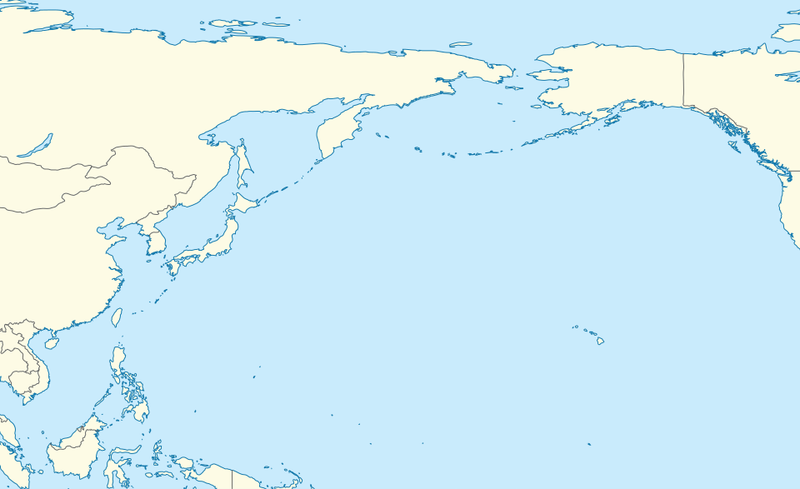

3. Over-Water Flying Is Constrained by How Far You Can Be from a Suitable Airport

Flying over the ocean is not as simple as pointing the nose toward your destination and going. Airlines must follow strict rules about how far their planes can fly from the nearest airport where they could land safely in an emergency.

These rules are part of what is often called ETOPS, which stands for Extended Operations.

ETOPS certification depends on the aircraft type, engine reliability, and the airline’s operational standards. A twin-engine jet might be approved to fly up to 180 minutes from the nearest suitable airport, while others can go even farther.

This approval shapes which routes are possible.

When planning a transpacific flight, dispatchers look at a map and draw circles around every airport that meets safety standards. The route must stay within those overlapping circles.

If a direct line would take the plane too far from any good diversion option, the route must curve to stay within the safe zone.

This is why some flights hug coastlines or island chains more closely than you might expect. Safety and regulations come first, and the path that looks indirect might actually be the only legal and smart choice.

4. Remote Does Not Just Mean Scary, It Means Slower Help and Fewer Options

When something goes wrong on a flight, time matters. A passenger might have a heart attack, smoke could fill the cabin, or a critical system might fail.

In any of these situations, pilots want to land as quickly as possible at an airport with good medical facilities, fire services, and maintenance support.

Flying over the middle of the Pacific Ocean means being hours away from help. Even if the plane can physically make it to an airport, the delay can be dangerous or costly.

Airlines consider this risk carefully when planning routes.

Route planners prefer paths that keep the aircraft closer to multiple diversion airports. Having options means faster response times and better outcomes if something unexpected happens.

It also means lower insurance costs and fewer logistical headaches for the airline.

This is not about fear; it is about smart planning. Passengers might never know how much thought goes into keeping them safe and close to help at all times.

The routes that seem to avoid the emptiest parts of the ocean are doing exactly that, providing a safety net that hopefully never gets used but is always there.

5. The Pacific Has Organized Highways in the Sky, and Flights Funnel into Them

Just like cars use highways instead of driving randomly across fields, airplanes follow organized routes called airways. Over the Pacific Ocean, these airways are carefully designed to manage the huge volume of traffic flying between Asia, North America, and Oceania.

Air traffic controllers need predictable flight paths to keep planes safely separated from each other. In oceanic airspace, where radar coverage is limited, this predictability becomes even more important.

Structured route systems, like the North Pacific route structures, create invisible highways that guide traffic efficiently.

These routes are not random. They are designed based on prevailing winds, safety considerations, and the locations of key waypoints where controllers can track aircraft.

Airlines file flight plans that follow these established tracks, which is why many flights seem to take similar paths.

The result is a concentration of traffic into specific corridors rather than planes spreading out evenly across the ocean. This might look like planes are avoiding certain areas, but really they are just following the most efficient and safest highways in the sky.

It is organized chaos that keeps thousands of flights moving smoothly every day.

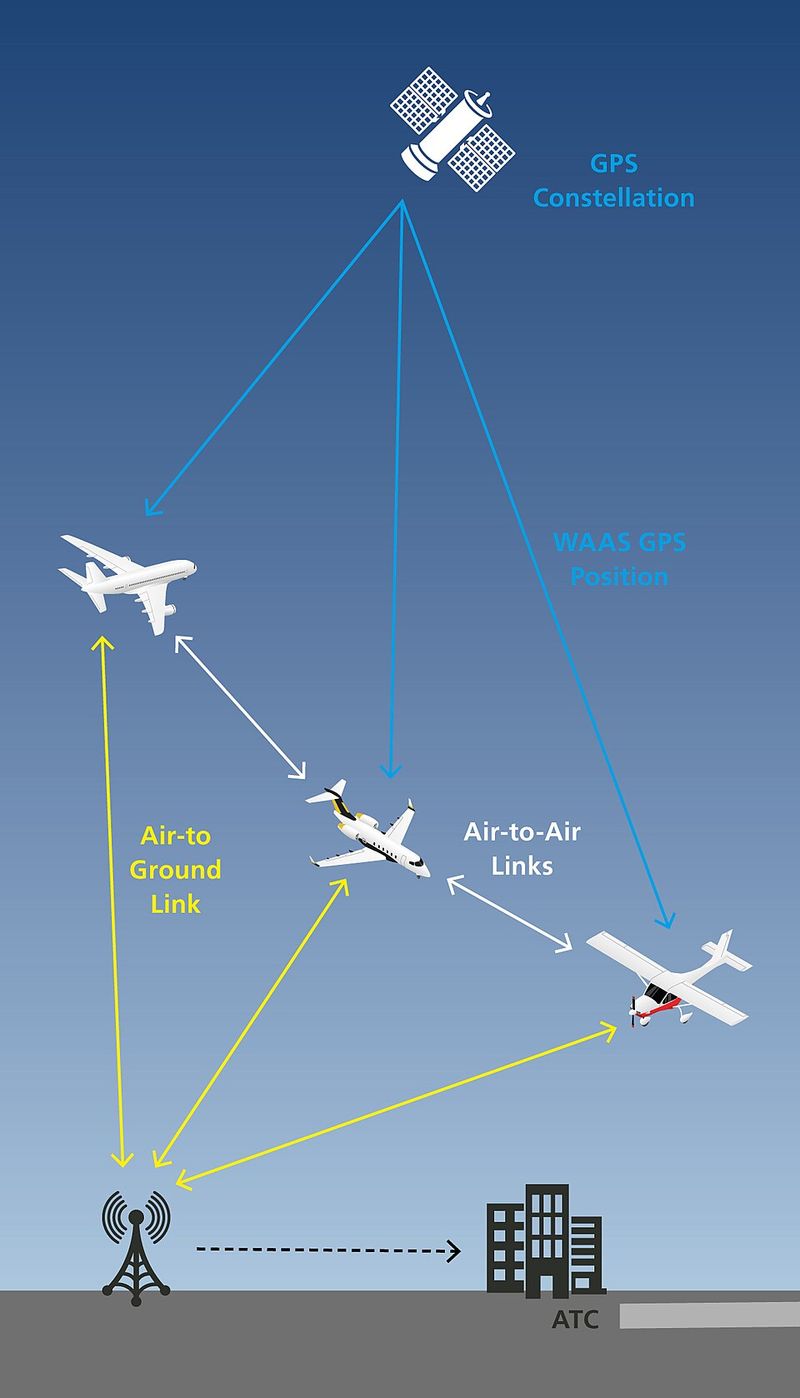

6. Oceanic Airspace Has Different Surveillance and Separation Realities than Land

When you fly over a city or populated area, ground-based radar stations track your plane constantly. Controllers can see exactly where you are and adjust your path in real time.

Over the ocean, this kind of radar coverage often does not exist, which changes how flights are managed.

In oceanic airspace, air traffic control relies on procedural separation. Pilots report their positions at specific waypoints using satellite communications or other long-range systems.

Controllers use these reports to ensure planes stay safely apart, but the process is less flexible than radar-based control.

This reality shapes where routes can go and how closely planes can fly together. Oceanic tracks are spaced farther apart, and changes to flight plans are less frequent.

The routes must be predictable and follow established procedures to maintain safety.

New technologies like ADS-B and satellite-based surveillance are improving oceanic operations, but many areas still rely on older methods. Route planners work within these constraints, choosing paths that fit the surveillance and communication capabilities available.

It is a balancing act between efficiency and the limitations of tracking planes over vast, empty expanses of water.

7. Communication Constraints: VHF Is Not Everywhere; HF and Data Link Matter

Most of us are used to clear, instant communication. But when you are flying over the middle of the ocean, staying in touch with air traffic control is more complicated.

The VHF radios that work perfectly over land have a limited range and do not reach across thousands of miles of water.

Instead, oceanic flights use HF (high frequency) radio and satellite-based data link systems like CPDLC (Controller-Pilot Data Link Communications). HF radio can travel long distances by bouncing signals off the atmosphere, but it is scratchier and less reliable than VHF.

Data link sends text messages between pilots and controllers, which is more reliable but slower.

These communication methods require special equipment, training, and procedures. Route choices sometimes reflect where communication coverage is strongest and most reliable.

Flying through areas with good satellite coverage or established HF frequencies makes operations smoother and safer.

Pilots and dispatchers plan routes that keep communication as robust as possible. Losing contact with ATC over the ocean is not an emergency, but it is something everyone wants to avoid.

The routes that seem to favor certain areas often do so partly because the communication infrastructure there is better and more dependable.

8. Winds Aloft Can Make a Longer-Looking Route Faster or Cheaper

Wind is invisible, but it has a huge impact on how fast and how far an airplane can fly. At cruising altitude, strong jet streams can blow at speeds over 200 miles per hour.

Flying with these winds pushes you along like a river current, saving time and fuel. Flying against them is like swimming upstream.

Airlines use sophisticated weather models to predict winds at different altitudes and locations. Dispatchers analyze this data and choose routes that take advantage of tailwinds and avoid headwinds, even if the path looks less direct on a map.

A route that is 100 miles longer but has 50 miles per hour of tailwind can actually be faster and cheaper.

This is especially important over the Pacific, where jet streams shift with the seasons. Winter routes between Asia and North America often differ from summer routes because the winds change.

What looks like a detour might actually shave an hour off your flight time.

Fuel is one of the biggest costs for airlines, so every decision about routing considers wind carefully. Passengers benefit from shorter flights and lower ticket prices, all thanks to invisible rivers of air high above the ocean.

9. Turbulence Avoidance: Comfort and Safety Both Matter

Turbulence is not usually dangerous to the airplane itself, but it can hurt people. Passengers and flight attendants who are not buckled in can be thrown against the ceiling or injured by flying objects.

Even moderate turbulence makes drink service impossible and leaves everyone feeling queasy.

Pilots and dispatchers have access to turbulence forecasts and reports from other flights. When they know an area is likely to be rough, they plan routes around it whenever possible.

This is part of everyday flight planning, not just a response to extreme weather.

Over the Pacific, certain areas are known for more turbulence due to jet streams, mountain wave activity, and convective weather. Routes that seem to take a longer path might be avoiding these rough patches.

Passengers appreciate the smoother ride, even if they never know the detour happened.

Airlines also care about turbulence because injuries lead to lawsuits, delays, and bad publicity. Avoiding known turbulence zones is a win for everyone.

So the next time your flight takes a path that seems indirect, it might be steering you away from a bumpy ride you never had to experience.

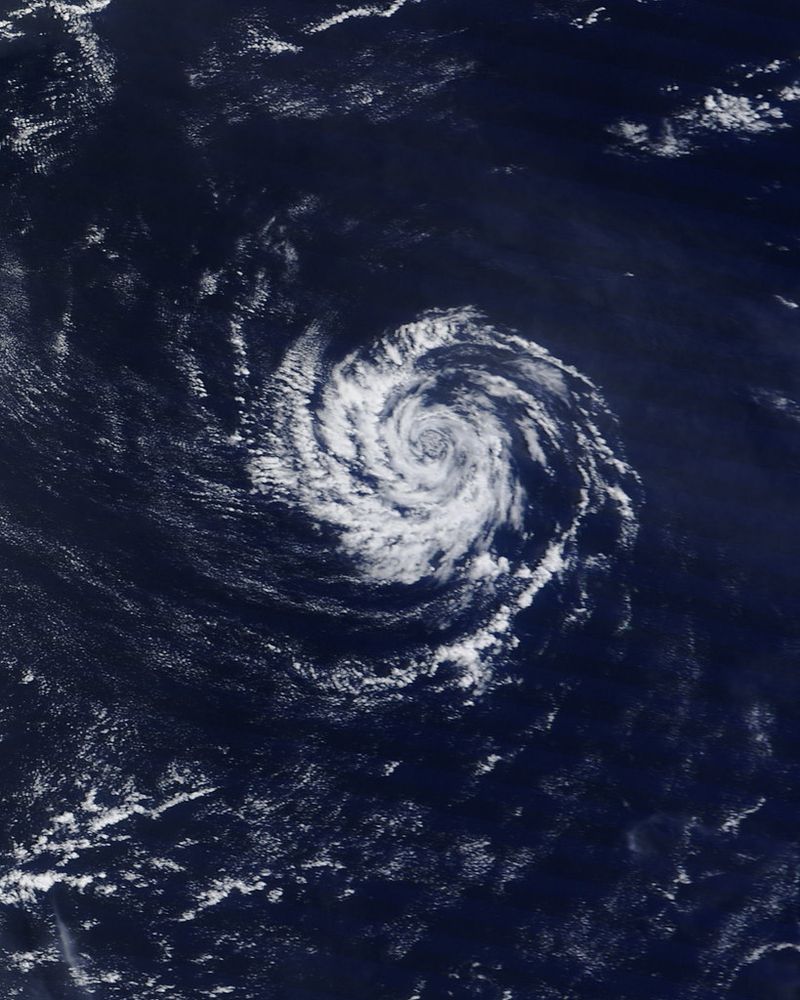

10. Tropical Cyclones and Oceanic Storm Systems Steer Routes

The Pacific Ocean is home to some of the most powerful storms on Earth. Tropical cyclones, known as typhoons in the western Pacific and hurricanes in the eastern Pacific, can span hundreds of miles and pack devastating winds.

Airlines give these storms a very wide berth.

Even when a cyclone is far from the planned route, dispatchers build in large safety buffers. Storms can change direction unexpectedly, and the turbulence and wind shear around them extend far beyond the visible clouds.

Flying anywhere near a tropical cyclone is dangerous and uncomfortable.

The Pacific also experiences other large storm systems, including mid-latitude lows and areas of severe convection. These systems can disrupt routes for days at a time, especially during the active typhoon season from May through November.

Flights that would normally take a direct path must detour around the storm zones.

Meteorologists work closely with airline operations centers to monitor developing storms and adjust routes in real time. Passengers might see their flight path change shortly before departure or even mid-flight if a storm moves unexpectedly.

These adjustments keep everyone safe and ensure the plane avoids the worst weather the Pacific has to offer.

11. Volcanic Ash Risk Is Real Around the Pacific Ring of Fire

The Pacific Ocean is surrounded by the Ring of Fire, a zone of intense volcanic and seismic activity. Dozens of active volcanoes dot the region, from the Aleutian Islands to Indonesia, Japan, and the Philippines.

When these volcanoes erupt, they can inject massive plumes of ash high into the atmosphere.

Volcanic ash is extremely dangerous to jet engines. The tiny, abrasive particles can melt inside the hot engine, solidify on turbine blades, and cause engines to fail.

Ash also damages windshields, clogs sensors, and contaminates aircraft systems. Pilots avoid volcanic ash at all costs.

When a volcano erupts, aviation authorities issue ash advisories and forecast where the plume will drift. Airlines immediately reroute flights to avoid the affected airspace, even if it means significant detours.

These reroutes can add hours to a flight and cost thousands of dollars in extra fuel, but the alternative is unacceptable.

The Ring of Fire means that Pacific routes are constantly monitored for volcanic activity. Dispatchers check volcanic ash advisories as part of routine flight planning.

Routes that seem to avoid certain areas might be steering clear of an ash cloud you never heard about, keeping you safe from a hidden danger in the sky.

12. Some Airspace Is Restricted or Strategically Inconvenient

Not all airspace is open for commercial flights. Military training areas, weapons testing zones, and politically sensitive regions can be off-limits or require special permission to enter.

Over the Pacific, these restricted areas can be large and force significant detours.

Some airspace restrictions are permanent, while others are temporary and activated for specific military exercises or operations. Flight planners must check NOTAMs (Notices to Airmen) daily to see which areas are closed.

Missing a restriction can lead to serious consequences, including interception by military aircraft.

Geopolitical considerations also play a role. Some countries charge high overflight fees, have complex permit requirements, or are avoided for security reasons.

Airlines weigh the cost and hassle of flying through certain airspace against the fuel cost of going around. Sometimes the detour is cheaper and simpler.

Over an ocean, detouring around a restricted area can mean a much larger deviation than it would over land, where there are more alternate routes. A 100-mile-wide restricted zone in the middle of the Pacific can force a flight to divert by several hundred miles.

These invisible boundaries shape the routes you fly more than you might realize.

13. Dispatch Planning: Alternates, Fuel Reserves, and What-If Scenarios

Every flight begins with a detailed plan that considers not just the route, but also what could go wrong. Dispatchers must choose alternate airports in case the destination is suddenly closed by weather or other problems.

They calculate how much extra fuel to carry for holding, diversions, and unexpected headwinds.

These contingency plans shape route choices. A route that looks efficient on paper might not provide good alternate airports or might require carrying so much extra fuel that the plane cannot take a full payload of passengers and cargo.

Dispatchers balance all these factors to find the best overall solution.

Over the Pacific, where diversion options are limited, this planning becomes even more critical. A route might be chosen because it passes near a good alternate airport, even if it is not the absolute shortest path.

The extra few minutes of flight time are worth the peace of mind and operational flexibility.

Airlines also consider the cost of diversions. Landing at a remote island airport might mean stranding passengers for days and flying in spare parts and crew.

Routes that minimize these risks are worth the extra fuel. The planning that goes into every flight is far more complex than most passengers ever realize.

14. Space Weather Can Affect HF Comms, GNSS Reliability, and Radiation Exposure

Space might seem far away, but solar storms and cosmic radiation can affect airplanes, especially on high-latitude and oceanic routes. When the sun releases a burst of charged particles, it can disrupt radio communications, interfere with GPS signals, and increase radiation exposure for passengers and crew.

HF radio, which is critical for oceanic communication, is particularly vulnerable to solar events. A strong solar flare can make HF communication impossible for hours, forcing pilots to rely on satellite data links or change altitude to find a frequency that works.

This uncertainty can influence route planning.

GPS and other satellite navigation systems can also be degraded by space weather. While aircraft have backup navigation methods, reduced GPS accuracy over the ocean is something dispatchers prefer to avoid.

Routes that pass through regions less affected by space weather might be chosen during active solar periods.

Radiation exposure is another concern, especially for crew members who fly frequently. High-latitude routes, which are common for transpacific flights, expose passengers and crew to higher radiation levels.

During major solar storms, airlines sometimes lower cruising altitudes or choose slightly lower-latitude routes to reduce exposure. It is a hidden factor that shapes where planes fly.

15. The Biggest Myth-Buster: Some Routes Must Cross the Pacific

After all this talk about routes avoiding the Pacific, here is the truth: many flights have no choice but to cross huge stretches of ocean. Flights from North America to Australia or New Zealand, routes connecting Pacific islands to continents, and many other journeys require flying over thousands of miles of water.

The difference is that these routes are planned with all the considerations we have discussed. Aircraft are chosen for their range and ETOPS capability.

Routes are designed to stay within reach of diversion airports whenever possible. Dispatchers monitor weather, winds, volcanic activity, and space weather to adjust the path as needed.

These flights do not avoid the Pacific; they cross it intelligently. The path might curve north to shorten the distance, follow established airways for traffic management, or detour around storms.

What looks like avoidance is actually careful planning that makes ocean crossings safe and efficient.

Millions of passengers fly over the Pacific every year without incident, thanks to the layers of planning, regulation, and technology that support these operations. The ocean is not avoided; it is respected and crossed with the knowledge and tools to do so safely.

Understanding this makes the engineering and planning behind modern aviation even more impressive.